Fiona McKergow

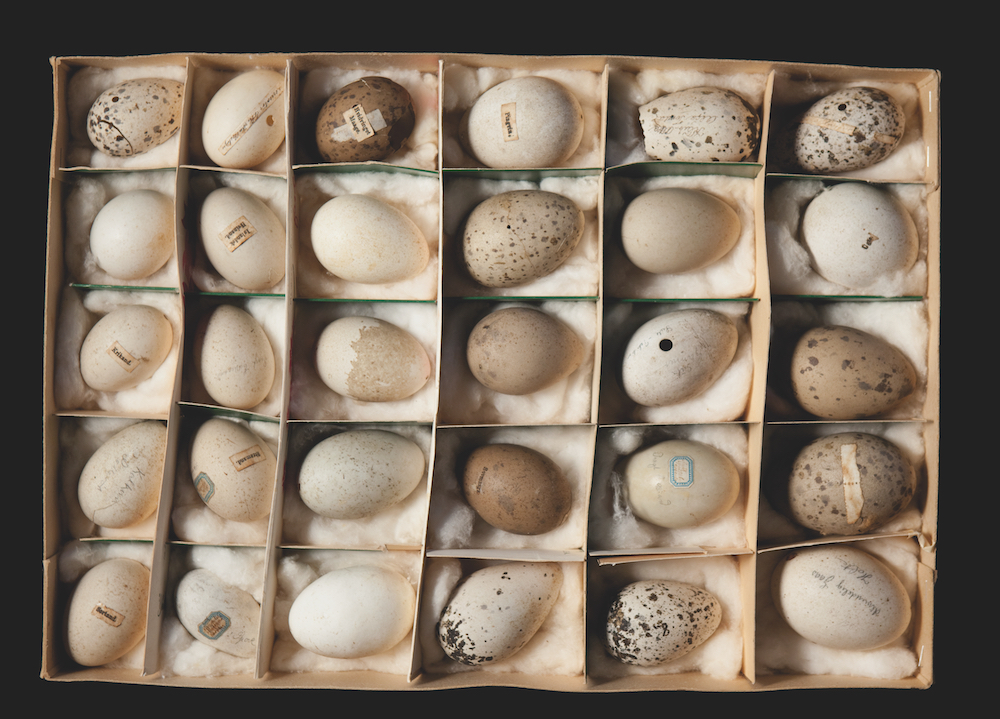

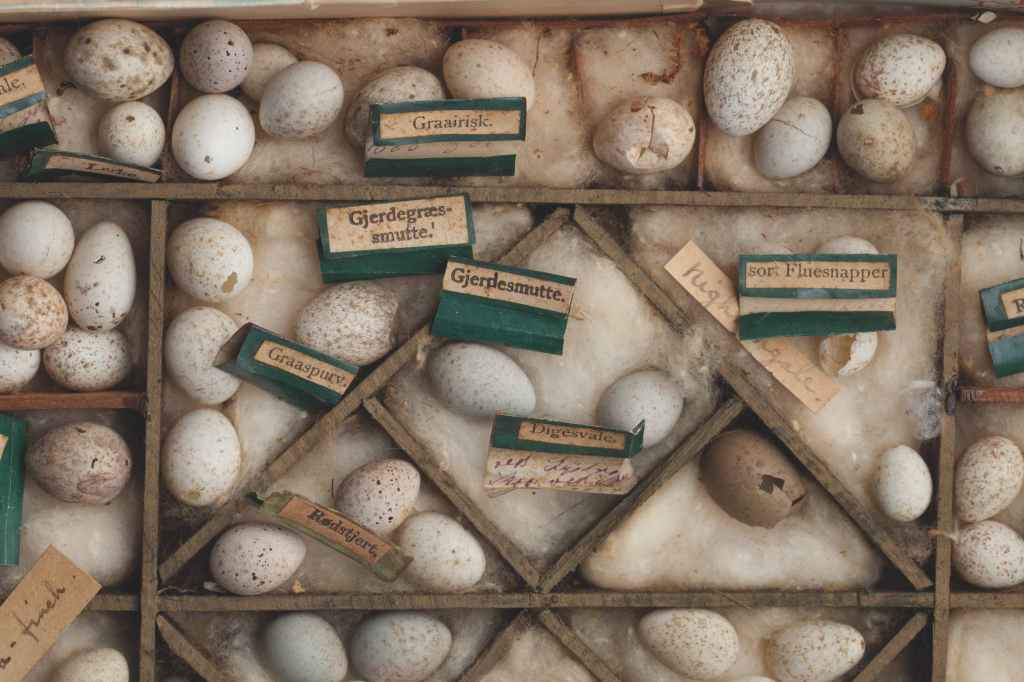

As your eye scans the carefully boxed birds’ eggs, it picks out inscriptions in an unfamiliar language: tagskægsvale, rørsanger, blaameise, halemeise, musvit, fluesnapper, digesvale, rødstjert, gjerdesmutte, among others. The eggs nestle in three boxes – two Canterbury menswear boxes and a shoebox – that are partitioned and padded with cottonwool. Many are beautifully marked and speckled; many are also obviously dirtied and discoloured with age. The labels vary in style: pencilled in an old-fashioned script directly onto the egg; inked or typed on slivers of paper or blue-edged stamps glued onto the egg; typed on tiny, loose pieces of shiny green paper. A few eggs are labelled in English. These observations indicate that the collection was made over a period of many years by a Danish immigrant.

Nineteenth-century natural history went well beyond visits to the museum. There was lively popular and academic interest in the natural sciences in colonial New Zealand. This had its origins in the work of scientific expeditions, laboratories and museums in Britain and Europe, but also in the stimulus provided by related institutions in New Zealand, such as the Colonial Museum in Wellington. Scientific information was widely circulated through public lectures, museum displays and various forms of print; influential treatises such as Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) provoked spirited debate. An interest in science also stemmed from day-to-day observation of the natural world. Nature study notes contributed by readers of newspapers show a shared curiosity for the flora and fauna at hand. Here, for example, is a snippet from ‘Makino Resident’ in the Feilding Star:

I thought it might be of interest to those of your readers who are fond of nature study to know that there was such a hawk’s nest built among some rushes on the property of Mr C.J. Hart, at Makino. The nest contains three young ones, two of which are fairly well grown, but the third seems to be a weakling. They are rather pretty for young birds and covered with fluffy tawny-colored hairs, while their wings and tails are edged with young feathers of a reddish brown colour.1

For many people, exploration of the natural world went beyond observation and found its expression in a love of collecting. Countless specimens were collected, preserved and displayed in private homes, schools, libraries and museums. Some private collectors simply amassed specimens. Others used the principles of classification and documentation developed by museum curators to organise their collections. This egg collection is believed to have been created by Wilhelm Larsen, who emigrated from Denmark to New Zealand in the early 1890s. It comprises around 240 eggs from about 44 bird species found in north-western Europe. The common names given to the eggs in Danish use an outmoded form of spelling; for instance, blaameise, or blue tit, is now known as blåmejse. The eggs are mainly from passerines, an order that includes sparrows, thrushes, finches, flycatchers and swallows. All are from birds whose conservation status is not of concern.

Inside the folded slips of green paper, the circumstances under which a number of the eggs were collected is recorded in cramped, old Danish using an ink that has faded to pale brown. The late Bodil Petersen, a Danish New Zealander who lived in Palmerston North, painstakingly interpreted the collector’s notes. With the aid of a magnifying glass, she discovered that the collection was begun in the 1870s (halvfjernerne means ‘the seventies’). The dates recorded inside the green labels continue to 1886. The eggs were found in gardens (have) and forests (skov) in the suburbs of Copenhagen, such as Holte. They were also found on farms (gaard) near villages just outside Copenhagen, such as Sollerod. Other locations include lakes (soe)and dykes (dige). Occasionally the labels record that an egg, such as that of a turkey (kalkun), was a gift from another person. No scientific names have been attributed other than for the genus Anas (dabbling ducks). While the documentation is scientifically worthless, it gives insight into the habits of an egg collector of modest means in a particular time and place.2

The three boxes of eggs are part of a larger collection that was donated to Manawatu Museum in 1975 by Mr C.E. (Eddie) Williams, then principal of Longburn School. There are 86 additional items in the collection, indicating that it was actively extended in New Zealand.3 The collection includes archaeological and ethnological material from Northern Europe and New Zealand, such as numerous adzes, chisels and arrowheads, and single examples of a flake, drillpoint, spearhead and sinker; taxidermied specimens, such as a tūī, falcon, grebe, penguin, starling, pheasants and weasels; New Zealand and Pacific marine organisms, such as shells, corals, cats eyes, starfish and sea urchins; pigs’s tusks; and a copper dish. Alan Nielsen, a resident of Longburn, had given the boxes of eggs and these other items, along with a tall glass-fronted cabinet that had been used to display them, to Longburn School in the mid-1960s.4

The collection had belonged to Alan’s father, Niels Peter Nielsen, who had left the cabinet with Alan and his wife Helena in the hallway of the family home at Tiakatahuna when he moved to Palmerston North late in life. When this property was sold in 1964, Alan and Helena could not fit it into their new home at Waituna West – perhaps more revealingly, they were ‘not fussed on taking it’. Helena recalled a bittern on top of the cabinet with a cobweb trailing from beak to chest, and bottled specimens: ‘Oh, the snakes in the jar annoyed me.’5 With no regional museum, Longburn School was an obvious recipient. Alan had been on the Longburn School Committee, Helena was involved in the school’s Parent Teacher Association, and three of their four children were pupils.6 The acceptance of the collection by the school may have resulted from a sense of community rather than reflected its educational merit.

It is possible to trace a changing attitude to the teaching of nature study in schools in the region during the mid-twentieth century. Mr E.H. Lange, instructor in agriculture for the Wanganui Education Board, summed this up in 1940:

Another encouraging sign is the increased use of the ‘continuous study’ in which the children observe plants, animals, and birds, etc., over an extended period. The value of this cannot be too highly stressed. It is hoped that this type of work will be carried out by more schools next year in place of collections of leaves, twigs, etc., which have little real nature study value.7

It is ironic that this collection ended up in a classroom decades after such static teaching aids were being dismissed. A former pupil said that the collection was ‘just there’ and did not remember it being used for educational purposes.8

Niels Peter Nielsen was born in Denmark in 1876.9 His parents, Anders and Ane Magrete Nielsen, emigrated to New Zealand in the early 1890s (possibly on the Orotava in 1891).10 Niels Peter married Botille Voss of Kairanga in 1900 and they had four children, one of whom, Maud Bindon, was questioned by Joanne Mackintosh, an education officer at Manawatu Museum, about her father’s collection in 1995.11 She stated that her grandparents came to New Zealand: ‘Because Grand-mother (Dad’s mother) had been ill and her Dr. recommended a sea-voyage would improve her health.’ At first they lived with her grandmother’s brother, Mads Larsen, who had settled at Fitzherbert, across the Manawatū River from Palmerston North. She confirmed that her father did not create the collection, but inherited it from his maternal uncle, Wilhelm Larsen. It was: ‘Just a hobby as far as I know.’ One of the folded labels bears the initials ‘V.L.’, which probably stand for Vilhelm (an old spelling of ‘Wilhelm’) Larsen. Maud confirmed that Wilhelm continued to collect natural history specimens in New Zealand.12

In addition to Niels Peter, their only son, Anders and Ane Nielsen also had two daughters; Laura Louise married Matthew Whitelock in 1901, and Johanne Marie married Max Burmeister in 1902. When their uncle Wilhelm died in 1911, each sibling inherited part of his collection, with three quite different outcomes. Louise Whitelock’s share is believed to remain in private hands. One of Johanne and Max’s sons, like others in his family, held a fierce passion for hunting and collecting. In 1977, in a prosecution brought by the Wildlife Division of the Department of Internal Affairs, he was convicted on 94 charges of possessing ‘absolutely protected’ bird specimens.13 A total of 112 taxidermied birds were confiscated, among them his mother’s inheritance. They included scientifically significant specimens such as a plumed egret and an Antarctic petrel rarely found in New Zealand. Attitudes to collecting had changed dramatically. Preservation now meant the protection natural habitat, not taxidermy. There was significant public distaste for traditional hunters and collectors, and even the once common childhood pursuits of bird nesting and egg collecting were also out of favour.

Looking back, it is astonishing that this amateur collection of fragile and fairly ordinary birds’ eggs survived such a multi-faceted journey: from Copenhagen to Palmerston North by sea, in and out of a series of family homes, a primary school classroom and a museum collection store. These eggs are a reminder of the conflicting attitudes that have influenced, and continue to influence, human relationships with nature: love, curiosity and respect intertwined with self-interest, greed and desecration.

First published in Fiona McKergow and Kerry Taylor, eds, Te Hao Nui – The Great Catch: Object Stories from Te Manawa, Random House, 2011; updated and republished with the author’s permission.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the late Bodil Petersen, Jon Fjeldså, the late Anne Nason and Richard Mildon for their assistance.

Footnotes

- Feilding Star, 22 December 1908, p. 2. ↩︎

- Evaluation provided by John Fjeldså, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, 8 December 2010. ↩︎

- It is possible that not all of the Nielsen collection was accessioned. Duplicates and items in poor condition usually went into the Education Collection for use by school groups. Notes from conversation with Jeannie Mitchinson, 5 June 1995, Nielsen Collection file, Te Manawa Museum. ↩︎

- See questionnaire filled out by Helena Nielsen, 1995, Nielsen Collection file, Te Manawa Museum. ↩︎

- Notes from conversation with Helena Nielsen, 20 April 1995, Nielsen Collection file, Te Manawa Museum. ↩︎

- See questionnaire filled out by Helena Nielsen, 1995, Nielsen Collection file, Te Manawa Museum. ↩︎

- Manawatu Evening Standard (MES), 2 February 1940, p. 3. ↩︎

- Notes from conversation with Alan Rowlands, undated, Nielsen Collection file, Te Manawa Museum. ↩︎

- Letter to Maud Bindon from Joanne Mackintosh, 10 April 1995, Nielsen Collection file, Te Manawa Museum. ↩︎

- MES, 30 April 1925, p. 5. ↩︎

- Alan Nielsen had died in 1982; see MES, 8 September 1982, p. 23. ↩︎

- See questionnaire filled out by Maud Bindon, 1995, Nielsen Collection file, Te Manawa Museum. Maud named him ‘Wilhelm Larsen’, but he is listed in official records as ‘Jens Vilhelm Larsen’. ↩︎

- MES, 5 April 1977, p. 1. ↩︎

Bibliography

‘Jon Fjeldså’, Wikipedia, URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jon_Fjelds%C3%A5, accessed 7 August 2024.

Nielsen Collection file, Te Manawa Museum.

Leave a comment