Tony Rasmussen

Two sets of footwear are among Te Manawa Museum’s collection of sports equipment.

A pair of women’s ankle-length marching boots show signs of having been well used: the leather is soft to the touch, especially on the inside, and the soles are heavily worn. Traces of white polish or paint brushed against the side of the sole to keep the boots clean and bright for marching competitions confirm their original function as an important and expensive piece of a marching uniform.1 At some point these boots have been embellished with a pair of metal-wheeled, adjustable roller skates of unknown brand. At the toe of each boot is a wooden block with a rubber pad to assist with braking. Underneath the toeplate on one of these boots, the name ‘Sanson’ has been written in pencil and what appear to be the initials ‘JS’ scratched alongside.

The other item is a pair of hobnailed work boots. So faded and scuffed that their original colour is hard to discern, they have layers of leather peeling apart at the heel, heavily scratched metal toeplates, worn soles and mismatched laces. Attached to these boots is a pair of non-adjustable chrome-plated size 6 Hamaco roller skates, which are noticeably small when the boots are viewed in profile. The inside surface of these boots is very rough, the heel and ball of the foot having left a deep impression inside each boot. What can these seemingly ordinary boots tell us about the people who once wore them, and the importance of roller-skating as a pastime?

The initials ‘JS’ on the marching boot identify its former owner as Janet Sanson. She and her brothers Roger and Melvin grew up on the farm of their parents, Arthur and Norah Sanson, at Glen Ōroua, 20 km west of Palmerston North, in the years after the Second World War. Like many families in New Zealand at this time, the Sansons recycled household goods and made do with everyday necessities. The Sanson children used these boots to participate in one of the crazes of the time – roller-skating. Melvin does not remember Janet having been part of a marching team, but he knows that she acquired these boots for roller-skating.2 He also remembers using a pair of Invicta skates, while Roger used the boots with these Hamaco skates. Steel roller-skate carriages fitted with wheels but without boots could be purchased at sports shops and toy departments in large stores in the decades after the war.

The Sansons joined other local youngsters to skate wherever and whenever they had the opportunity. The favourite local skating haunt was a large woolshed on the nearby Saunders farm. This building also hosted gatherings such as dances, twenty-firsts and wedding receptions.3 The children of Glen Ōroua skated around the large wooden floor, shouting with joy as the noise of wooden and metal wheels echoed off the walls. The woolshed offered a freedom to skate that was not necessarily available to the users of public rinks, such as the one in Foxton’s Coronation Hall.4 At Rongotea, near Glen Ōroua, the Town Board had banned roller-skating in the Coronation Hall.5 What energetic young skaters really needed were purpose-built skating rinks – public venues with a large, smooth surface enclosed by a metal safety rail and seating for spectators.

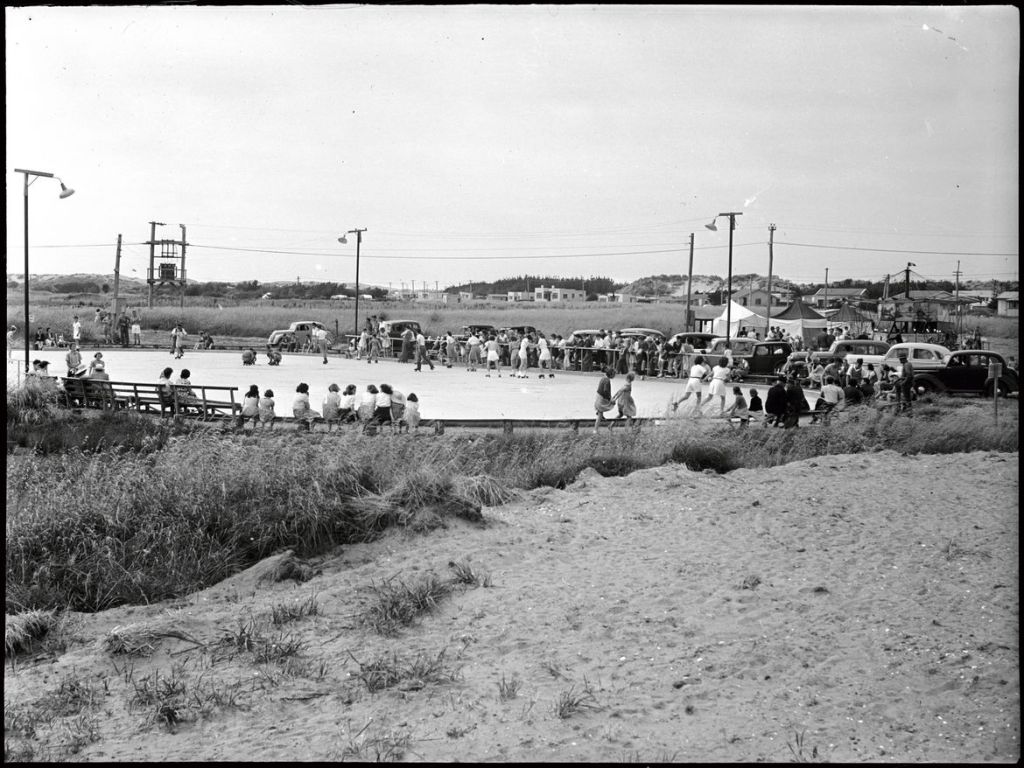

The Sansons found such a place in the Foxton Beach skating rink, which had been since at least 1945. They remember summer holidays with special affection, because they got the opportunity to skate at a rink near the centre of the bustling seaside community. The rink offered supervised skating every day. Pendants fluttered in the breeze, popular music was played on vinyl records and announcements were made over a loudspeaker. The rink manager’s regular exhortations to skaters to move in unison and be safety-conscious rang out above the grinding din of metal skate wheels on a concrete floor. Parents watched the young skaters from tiered seating.

Eventually the Foxton Beach rink grew into a multi-purpose, day-and-night entertainment venue with a stage and a sound shell, surrounded by a high corrugated iron fence. During the summer, concerts, fashion parades and beauty contests were held. Youngsters could skate on the rink during the day and come back in the evening with their families to enjoy a live concert under floodlights. A local skating club was formed, with its own uniforms:

Foxton Beach are proud of their skaters, for on Thursday nights at club practice everyone turns out in full uniform green and white; girls in white tops and green pleated skirts, and boys in white shirts and green shorts. They all look very smart indeed.6

When it was not being used for competitive artistic roller-skating, children with ordinary skating footwear, like the Sansons, could have a go on the high-quality, well-maintained rink. The durable concrete surface could take the punishment meted out by dozens of sets of metal wheels grinding across the smooth surface. This would have compensated for the weight of Roger’s boots, which are noticeably heavier than the marching boots.

Rinks that attracted a large number of people were also liable to lure a disorderly element, especially if there was no formal supervision. The Himatangi Beach Development Company Ltd (later the Himatangi Beach Progressive Society) which developed the settlement from the 1940s made the construction of a skating rink a priority, along with other recreational facilities such as a boating lake, trampoline park, tennis court and camping ground.7 Growing numbers of holidaymakers, including day-trippers from Palmerston North, led to disorderly behaviour between young people at the skating rink. The police were sometimes called in.8

The skating rink as a gathering place, a place of festivity even, had been an important part of skating culture for nearly a century. Skating was very popular in Europe and North America from the 1860s, when two technical developments that can be seen in these skates enhanced skater comfort and made the sport relatively easy to learn. The first was the invention of the four-wheeled ‘quad skate’ by James Plimpton, an American, in 1863.9 The four wheels were arranged in two pairs that were fitted to the footplate with a hinge, allowing the skate to turn. Earlier skates were modelled on ice skates and designed ‘in-line’ (with wheels one behind the other). The second improvement was the construction of wheels fitted with ball bearings. A line of small steel balls inside the rim of the wheel greatly increased load-bearing capacity and smoothness of ride. These radical innovations enabled skaters to move together in loose formation, creating a sight both pleasing and, at times, amusing to spectators, as ‘spills’ were frequent.

Skating rinks had to be substantial enough to accommodate large groups of skaters and spectators. Public halls were usually shared with other clubs and groups and available to skaters only at certain times. Palmerston North’s first skating rink, which opened in the Foresters’ Hall in June 1877, was shared with a public reading room. It operated from 7 to 10 p.m. each evening, with skates hired out at 1s an hour. Ladies were able to skate free of charge in the afternoons.10 Feilding soon followed suit, announcing its intention to open a ‘Skating Rink and Dancing School’ in 1879.11 Patrons at the Acme Roller Skating Rink, which opened in Feilding in 1889, were entertained by the Feilding Brass Band; ‘special sessions for ladies’ were advertised.12 In the same year a purpose-built rink was erected by Kibblewhite and Thomas on Palmerston North’s Broad Street (now Broadway) for Maurice Lyons, a local tobacconist.13 In 1891 this property was bought by the Salvation Army as part of a strategy of purchasing skating rinks for evangelistic activities.14

Before roller skates became widely available, they were hired out at rinks. As people became more proficient at skating, demand for quality skates grew. The Excelsior, another Feilding rink, boasted of having obtained ‘a first-class collection of the latest design in American roller skates’.15 Good-quality equipment allowed skaters to hone their skills to the point where, according to the Manawatu Times, ‘Quite a number of Palmerstonians are becoming expert in the more intricate ways of back-skating, etc.’16 In 1905, roller skates with ball-bearing wheels were introduced at the Zealandia Skating Rink in Broad Street.17

The construction of rinks like the one at Foxton Beach, while catering to the recreational needs of skaters, also signalled increasing interest in competition-level roller skating. This was organised at a national level for the first time with the formation of the New Zealand Roller Skating Association in Christchurch in 1937.18 In Palmerston North after the Second World War, one venue in particular was both of competition standard and also popular with recreational skaters. The site of an old railway gravel pit had been set aside for beautification in the late 1930s. Fundraising resumed after the war and it was officially opened as Memorial Park on 3 December 1954. The top-class skating rink was complemented by sports and play grounds.

Indoor venues were more common. The Izadium, an indoor sports facility on Fitzherbert Avenue, attracted high-profile skating competitions. In June 1962 the New Zealand Roller Skating Association held trials there to select a 40-strong team to attend the World Congress amateur championships in Brisbane.19 Another competition rink at the Pascal Street Stadium was the home of the Manawatu Showgrounds Skating Club. In 1974, 29 members of this club qualified to compete in the national skating championships in Whanganui.20 With skating now a serious business, substandard equipment was barred from some rinks. The Izadium permitted only skates with wooden or plastic wheels that were ‘in first class order’.21 Metal wheels such as those on the Sansons’ skates were considered too harsh to use on a smooth wooden floor.

The rise of competitive roller skating did not diminish enthusiasm for recreational skating. In 1981, Skateworld opened in Church Street, Palmerston North. This was the third rink to be opened by the Hutson family, who also operated rinks in Hamilton and Tauranga. Skating was becoming big business.22 When Skateworld closed in 1986, Palmerston North skaters moved to the Bell Hall in Waldegrave Street, where a manager was appointed to run skating sessions. In an effort to revive interest in leisurely skating, organisers named the new facility ‘Rollaway’.23

The face of skating has changed drastically since the 1980s. Thanks to the rise of in-line skating (rollerblading) in the 1990s and a resurgence in skateboarding, outdoor skating environments have become more popular. Palmerston North youth lobbied the city council for a purpose-built skate park that was eventually built – with design input and advice from local skaters – in 2001. Its organisers claimed that: ‘The Railway Land Skate Park will increase Palmerston North’s reputation as … a major sports centre [and] will empower young people in the community to participate and work towards meeting their own recreational needs’.24

An ongoing commitment by communities to building accessible outdoor facilities such as skating rinks and skate parks has ensured that recreational skating continues to be enjoyed by new generations of New Zealanders – just as it was when the Sanson kids found their feet and got their skates on in the 1950s.

First published in Fiona McKergow and Kerry Taylor, eds, Te Hao Nui – The Great Catch: Object Stories from Te Manawa, Random House, 2011; updated and republished with the author’s permission.

Footnotes

- Macdonald, ‘Moving in Unison, Dressing in Uniform’, p. 195. ↩︎

- Melvin Sanson, conversation with Tony Rasmussen, 19 March 2010. ↩︎

- Bryan Saunders, conversation with Tony Rasmussen, 18 March 2010. ↩︎

- ‘Coronation Hall and Town Hall, Foxton’, URL: https://horowhenua.kete.net.nz/item/215de495-2675-45f9-96da-6b0764a21955, accessed 14 August 2024. ↩︎

- Holcroft, The Line of the Road, p. 157. ↩︎

- Amaroskate Magazine, vol. 2, no. 10, March 1964, p. 102. ↩︎

- Audit Records of the Himatangi Beach Company, 1939–1970, Te Manawa Museums Trust. ↩︎

- Holcroft, The Line of the Road, p. 171. ↩︎

- ‘James Plimpton: American inventor’, Britannica Online. ↩︎

- Manawatu Times (MT), 9 June 1877, p. 2. ↩︎

- MT, 7 June 1879, p. 3. ↩︎

- Feilding Star (FS), 25 April 1889, p. 2. ↩︎

- ‘Palmerston North Corps History’, Salvation Army Archives, Booth House, Wellington. ↩︎

- War Cry, 16 May 1891, p. 2. ↩︎

- FS, 22 June 1895, p. 2. ↩︎

- MT, 29 August 1905, p. 5. ↩︎

- Manawatu Standard, 16 August 1905, p. 5. ↩︎

- McLintock, An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, p. 259; Pollock, ‘Roller skating and skate boarding – Roller skating’. ↩︎

- Manawatu Evening Standard (MES), 24 May 1962, p. 14. ↩︎

- MES, 21 December 1974, p. 8. ↩︎

- MES, 24 May 1962, p. 14. ↩︎

- MES, 28 April 1981, p. 26. ↩︎

- MES, 25 February 1987, p. 3. ↩︎

- Palmerston North Skate Park Syndicate Management Plan, April 2001. ↩︎

Bibliography

Holcroft, M.H.,The Line of the Road: A History of Manawatu County, Manawatu County Council and John McIndoe, Dunedin, 1977.

‘James Plimpton: American inventor’, Britannica Online, URL: https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-Plimpton, accessed 14 August 2024.

Macdonald, Charlotte, ‘Moving in Unison, Dressing in Uniform: Stepping Out in Style with Marching Teams’, in Bronwyn Labrum, Fiona McKergow and Stephanie Gibson (eds), Looking Flash: Clothing in Aotearoa New Zealand, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2007.

McLintock, A.H., ed., ‘Skating, Roller’, An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, vol. 3, Reed, 1966, pp. 259–63.

Pollock, Kerryn, ‘Roller skating and skateboarding – Roller skating’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, URL: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/roller-skating-and-skateboarding/page-1, accessed 14 August 2024.

Leave a comment