Miriam Sharland

Pineapple Lumps, Snifters, Sparkles, Sherbet Fizz … . Sweets – lollies – are tiny sugary time machines that instantly transport us back to childhood: sucking Minties on long car journeys, rolling Jaffas down the aisle at the pictures, standing outside the dairy ‘smoking’ Spaceman cigarettes in an attempt to look cool. In his book Sweet Talk: The Secret History of Confectionery, Nicholas Whittaker observes, ‘As a set of cultural references, [sweets] form part of a common past.’1 And indeed, Tangy Fruits, Milk Bottles, Eskimos and the rest all form part of New Zealand’s common cultural heritage. Although many of these lollies are still in production, others, sadly, have been consigned to history. Boiled sweets in particular have become unfashionable. But even those that have gone remain part of our culinary and social history.

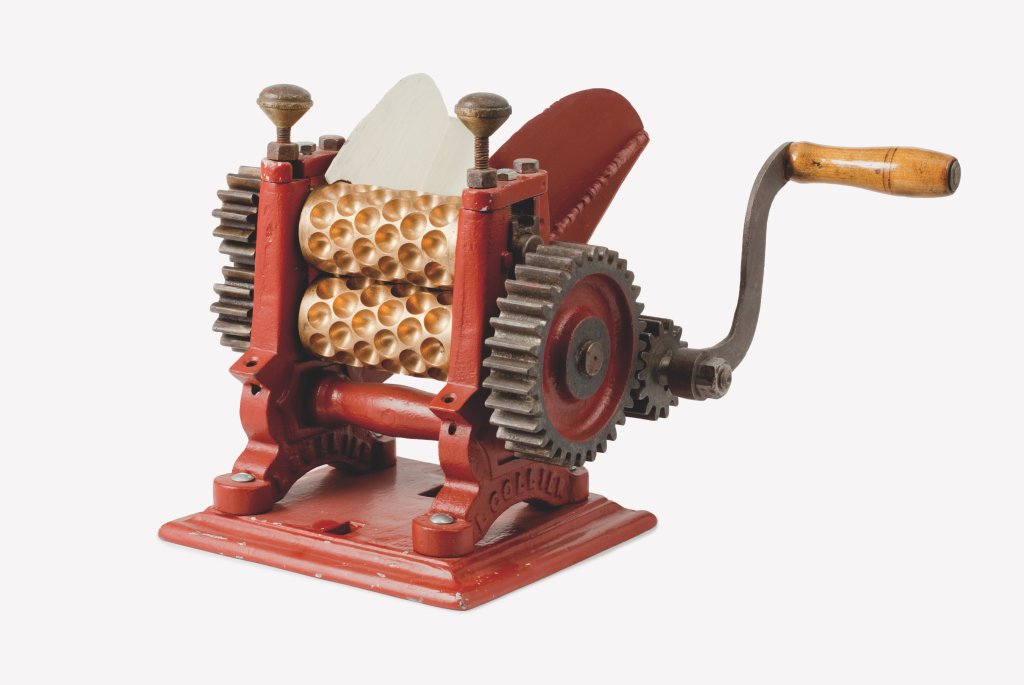

Paul Tonson remembers cough drops and butterscotch being made by his father Bob at home in Palmerston North in the 1950s with a boiled sweet-rolling machine, known in the confectionery trade as a drop roller. The machine, manufactured in England by L. Collier, is made of red-painted cast iron and has a pair of brass rollers that are indented with rows of tiny moulds. With the machine clamped to a table, the sugary boiled sweet mixture (called toffee in the trade) was fed through a metal chute at one end and cranked through the rollers using a manual handle on its side. As the rollers rotated against each other, the moulds formed a perfectly shaped spherical drop.

Confectionery sugar runs in the Tonson family’s blood. Paul’s great-grandmother Sarah Tonson arrived in Auckland from Bury, England in 1878 and was widowed the same year. She ran a sweet shop on Karangahape Road in the 1880s and 1890s, and family tradition recalls that she eloped with another sweetmaker. Sarah died in 1899.2 In that year, her son James was working as a sugar boiler in Auckland. He later moved to Palmerston North, where he continued the family trade and had six children who helped out during school holidays. Two sons, Jim and Bob (Paul’s father), followed James into the confectionery business. Jim established Regent Confectionery in Wellington in 1935. When Regent moved to Fitzherbert Avenue, Palmerston North in 1948, Bob was employed as Confectionery Manager.3

Palmerston North has been home to several confectioners over the years, including the brothers Phomen and Bir Singh, who were the first identifiable Sikh immigrants to New Zealand. In the 1920s, Phomen opened two Eureka sweet shops in Palmerston North, on The Square and Rangitikei Street. Phomen, his English wife and their children prepared English-style confectionery at home at 16 Andrew Young Street. The sweets were sold in the surrounding countryside from a horsedrawn van.4 Later sweetmakers included Gold Star on Rangitikei Street; Grants on Church Street, next door to the Grand Hotel; and the proprietor of the Mayfair Theatre cinema on George Street (now Harvey Norman), who made sweets for patrons. The number of confectioners in Palmerston North dropped dramatically from fifteen in 1948 when the Tonsons set up Regent there to six when the company was wound up in 1957.5 That was when the Tonson household acquired the sweet-roller machine.

After Regent closed down, Bob Tonson worked for Choice Confectionery on Main Street, Palmerston North. His sons Paul and John worked there during school holidays. Choice started life in the 1940s in a small shed in the backyard of a house in Albert Street. Don Longworth, a former employee of the company, now named Carousel Confectionery, remembered that in 1948, ‘When I was knee high to a grasshopper, I used to go with my uncle on the Chevy 4 to Feilding and deliver four-gallon tins to the shops.’6 These were the days before sweets were individually plastic-wrapped.

Boiled sweets are made by heating a solution of sugar and water to approximately 149oC. At this temperature, most of the water has boiled away and the remaining solution is about 98 per cent sugar. Then comes the tricky part: controlling the cooling stage without the sugar forming crystals, which give sweets a grainy appearance. A transparent, sparkling result is achieved by rapid cooling, traditionally by pouring the toffee onto a cold marble slab, at which stage colours and flavours are added. The discovery that crystal formation can also be prevented by adding acid from fruit juice or grapes made the industrial production of boiled sweets possible.7

Sugar and sweets are now a regular part of a typical Western diet. But although common and cheap today, sugar was an exotic and expensive luxury until about 1700. Europeans initially treated it as a spice and used it sparingly to flavour foods. It was also used as a medicine to cure stomach disorders, and to sweeten drugs. The first ‘confections’ were created by apothecaries to preserve and disguise the taste of drugs (much like modern-day cough lozenges). The first boiled sweets were made in the 1700s. They were initially a technical novelty, achieved through years of technological development and careful experimentation with ingredients, cooking temperatures, and boiling and cooling techniques. Sugar work of this kind – the transformation of grainy sugar into luminous, transparent sweets, glowing like jewels – appeared almost as a form of alchemy.

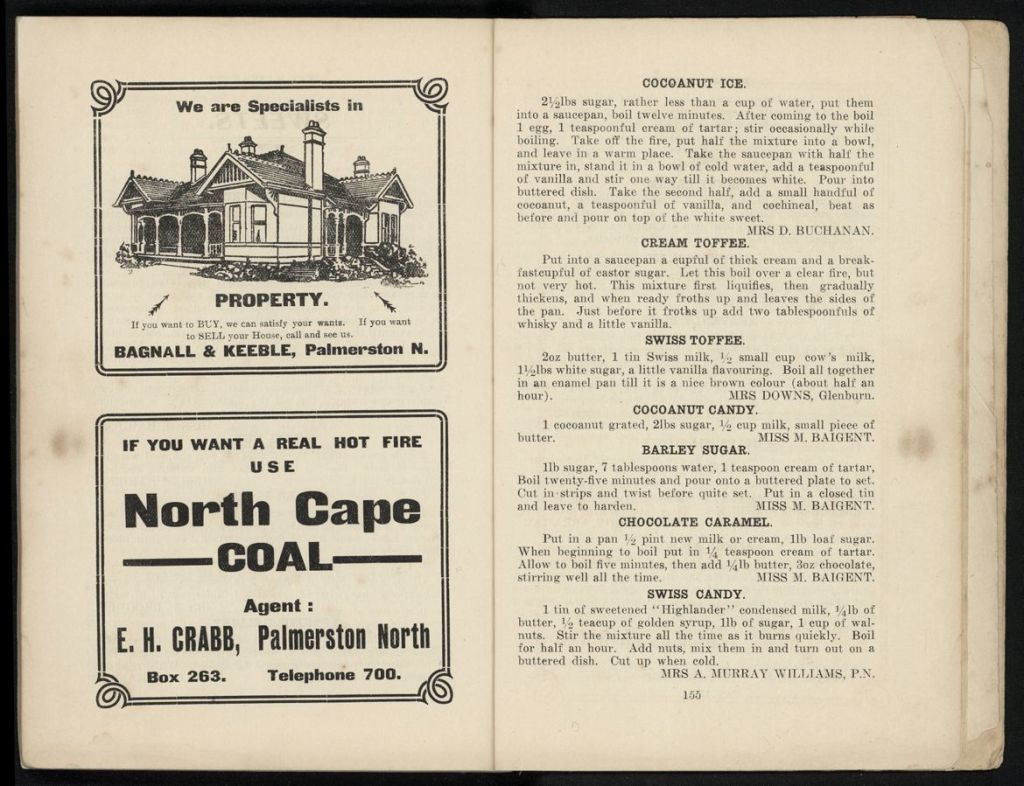

When the word ‘lollipop’ made its first appearance in 1784, it just meant sweets. Lollipops didn’t get their defining feature, the stick, until the early 1900s – after the invention of a machine that could insert them. The abbreviated term ‘lollies’, of course, remains a distinctive local parlance for sweets, with or without sticks, in Australasia.8 New Zealand’s confectionery culture, like its cuisine generally, is inherited from Britain. In Tim Richardson’s book Sweets: A History of Temptation, the author recounts how the first British settlers had a sweet tooth in common with Māori. In the 1840s, Thomas Brunner reported eating fern root moistened with dark brown sugar crystals from the pith of the cordyline plant (cabbage tree); it tasted like gingerbread.9 Lollies were often made at home by settlers in New Zealand, as they had been in Britain. Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century cookery books such as Mrs Beeton’s in Britain and Colonial Everyday Cookery in New Zealand contained recipes for confectionery.10

Although confectionery started out as a cottage industry, the trade was being mechanised by the time the first Europeans settled in New Zealand. While previously boiled drops had been laboriously cut from a sausage of toffee by hand with scissors – and they still were at home – the sweet-roller machine allowed commercial production of drops on a much larger scale. Manually operated rollers were used from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s to produce moulded fruit drops, the pinnacle of the sweetmaker’s art. In 1835 Luke Collier set up Collier’s brass founders to manufacture drop rollers in Rochdale, northern England. Some of his first products were drop rollers. Collier’s made the Tonsons’ sweet-rolling machine, which dates it to between 1835 and 1913, when Collier’s was sold to William Brierley.11 The firm of BCH Ltd (Brierley, Collier & Hartley) is still in business today as a food industry engineer, making drop-roller machines to a basic design that has changed little since the 1800s.

The 1928 edition of Skuse’s Complete Confectioner, the industry bible, contained illustrations of similar roller machines, which were a vital part of the confectioner’s kit. Skuse’s advised that ‘For drop making, some form of drop machine … is indispensable.’ The machines were a standard size so that interchangeable rollers with different designs could be fitted to produce shapes such as leaves, fruit, letters, shells and animals, and quirky designs such as beehives, teapots and baskets of flowers. As Skuse’s put it, ‘Interchangeable rollers of all patterns can be obtained in great variety to cut such forms as animals, leaves, pears, raspberries or almost any shapes.’ It added: ‘The small size machine will turn out 2 to 3 cwt. [hundredweight] of drops per diem, which for retail trade would generally suffice.’12 A hundredweight is about 50 kg – a lot of sweets to make with a hand-cranked machine.

As production became increasingly industrialised, hand rollers were superseded by much larger mechanised machines which worked on the same principle. Don Longworth recalls that sweetmaking at Choice slowly became mechanised during the 1960s. Skuse’s has an illustration of an automatic plate drop-roller machine with six pairs of drop rollers attached. This machine turned out about 300 lb (660 kg) of drops an hour.

The Tonsons’ sweet-rolling machine eventually fell into disuse and sat in the outhouse of the family home until it was donated to The Science Centre & Manawatu Museum by the family in 1994. The machine and the lollies it produced remain an important part of our cultural heritage. They remind us how a sweet little next-to-nothing can create an emotional link to our shared past, and with one mouthful, make each of us time travellers.

First published in Fiona McKergow and Kerry Taylor, eds, Te Hao Nui – The Great Catch: Object Stories from Te Manawa, Random House, 2011; updated and republished with the author’s permission.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Paul Tonson, Helen Leach and Don Longworth.

Footnotes

- Whittaker, Sweet Talk, p. 8. ↩︎

- Email from Paul Tonson to Miriam Sharland, 9 July 2010. ↩︎

- CO-W 1 Box 61 1052 Regent Confectionery Company, Archives New Zealand, Wellington. ↩︎

- McLeod, ‘Singh, Phomen’. ↩︎

- Wise’s New Zealand Post Office Directory, 1953–4, vol. 2, pt 2, p. 1885. ↩︎

- Don Longworth, conversation with Miriam Sharland, 3 November 2009. ↩︎

- McGee, On Food and Cooking, pp. 410–17. ↩︎

- Ayto, An A-Z of Food and Drink, p. 193. ↩︎

- Richardson, Sweets, p. 330. ↩︎

- Beeton, Mrs Beeton’s Everyday Cookery and Housekeeping Book; Anon., Colonial Everyday Cookery. ↩︎

- BCH, ‘Our History’. ↩︎

- Skuse’s Complete Confectioner, p. 33. ↩︎

Bibliography

Anon., Colonial Everyday Cookery, Whitcombe & Tombs, Christchurch, 1901.

Ayto, John, An A–Z of Food and Drink, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2002, cited in ‘The Food Timeline: History notes – candy’, URL: https://www.foodtimeline.org/foodcandy.html#lollipops, accessed 19 August 2024.

BCH Limited, ‘Our History’, URL: https://bchltd.com/about/history/, accessed 19 August 2024.

Beeton, Isabella, Mrs Beeton’s Everyday Cookery and Housekeeping Book, Ward, Lock & Co., Ltd, London.

McGee, Harold, On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen, 3rd edn, Unwin Hyman Ltd, London, 1984.

McLeod, W.H., ‘Singh, Phomen’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1996. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3s20/singh-phomen, accessed 19 August 2024.

Richardson, Tim, Sweets: A History of Temptation, Bantam Press, London, 2002.

Skuse’s Complete Confectioner: A Practical Guide to the Art of Sugar Boiling in All Its Branches, W.J. Bush & Co., London, 12th edn, 1928.

Whittaker, Nicholas, Sweet Talk: The Secret History of Confectionery, Victor Gollancz, London, 1998.

Leave a comment