Kerry Bethell

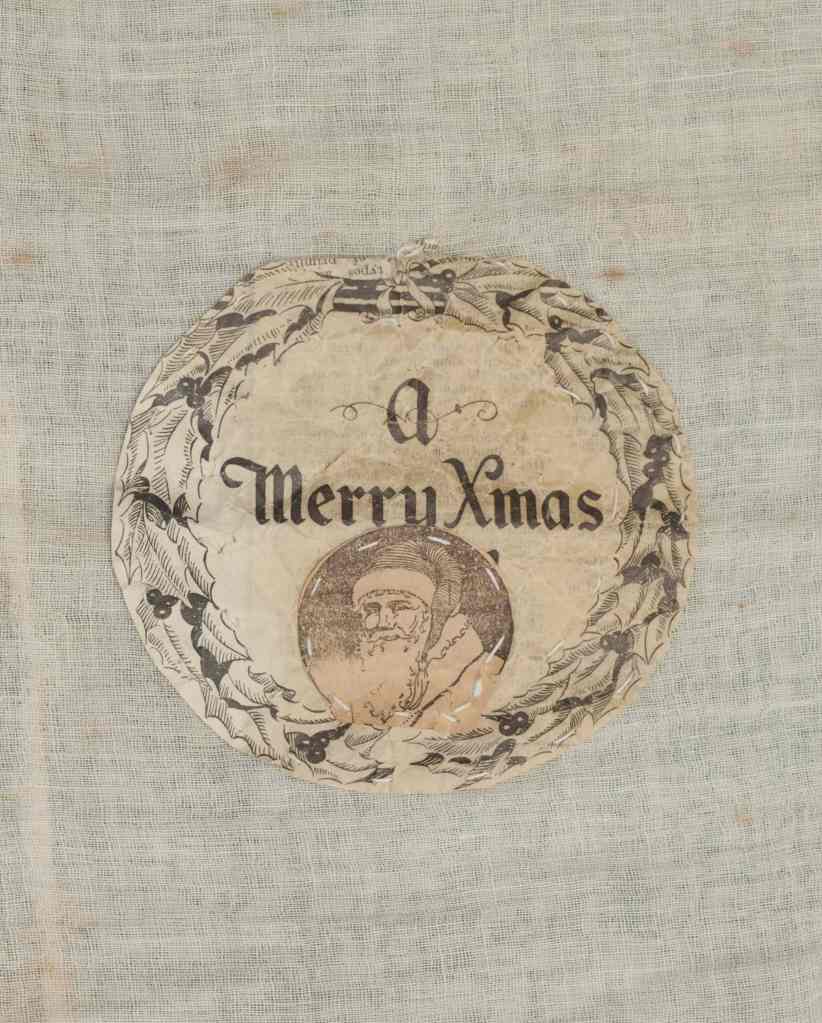

Doris Collins was about ten years old when her teacher at Awahuri School asked her to sew this Christmas stocking. Made of muslin – a light, cotton, typically white fabric – the stocking is simply constructed with hand-stitched seams. The only decoration is a commercially printed circle of paper depicting Christmas symbols – an image of Father Christmas, a wreath of holly and an inscription, ‘A Merry Xmas’. The stocking is somewhat misshapen, not just because it was made by a child but because it is difficult to sew a fabric as loosely woven as muslin.

Doris kept her hand-sewn stocking for the rest of her life. She also kept eight schoolbooks from her senior years of primary schooling, between mid 1915 and late 1918. Together these artefacts provide glimpses of what a girl might have learned from the early twentieth-century primary school curriculum, and what choices were available to her.

Doris Jean Collins was born on 22 April 1904. She was the younger daughter of Clara May Rowson and her husband, Arthur George Collins. Doris’s early life was centred within a rural environment and a Pākehā society built around notions of separate spheres for male and female. In 1908 the family moved to a new home and a farm on Rongotea Road, Awahuri, north of Palmerston North.

In November 1909, aged 5½, Doris was enrolled at the nearby Kairanga School. A year later Doris, along with her older sister Enid, was transferred to Awahuri School, a small public primary school for children from the nearby rural community, where she remained until November 1918.1 Doris had a settled childhood except for one defining event in August 1914 when her mother died suddenly and unexpectedly.2

Since the 1877 Education Act, a basic primary education had been seen as the birthright of every child in New Zealand. Awahuri School was a mixed-sex school with around 60 children aged between five and fourteen and two teachers, a headmaster and a female assistant. As with many rural schools in the area, Māori children attended the school alongside their European counterparts. Though the compulsory starting age was seven, Doris, like many others, started primary school at the permissive age of five. While children had equal access to primary schooling, boys and girls did not follow the same curriculum.

A revolutionary new curriculum designed to meet modern requirements had been introduced in the year of Doris’s birth. This aimed to replace book-learning with practical teaching that would be ‘closer to life’.3 The number of compulsory core subjects was increased from three to nine. Manual pursuits such as paper-folding, plasticine modelling, brushwork and gardening were introduced.

The new curriculum also aimed to ‘assist boys and girls, according to their different needs, to fit themselves, practically as well as intellectually, for the work of life.’4 In 1916 the Minister of Education stressed that every girl was to receive sufficient domestic training to ‘render her great future work a source of interest and pleasure’.5 In addition to the traditional core subjects, Doris was now to be instructed in cookery, hygiene and homecraft, fields in which ‘good, practical lessons of lifelong value were given with satisfactory results.’6

For their part, boys were to be taught woodwork, farming and military training. The new curriculum had no detailed prescriptions. Schools arranged programmes of study to fit their specific circumstances and the resources available. The authorities urged that lessons be taught in ‘relation to each other and with reference to the surroundings of the children.’ This was an educational system that sought to advance progressive ideals through prevailing norms.7

Needlework became a required subject for all girls. The emphasis was on practical plain sewing rather than creative or fancy-work such as smocking. Women, it was thought, had both a need and a duty to be able to sew. One aim was to foster hand–eye coordination. Doris had to demonstrate she had acquired skills such as planning, measuring, drafting, cutting and basic sewing. While the emphasis was on the doing, a completed stocking was required for a pass. However, concern was growing that girls’ eyesight was being damaged by fine sewing in inadequate light. The revised 1913 syllabus allowed senior girls to be exempted from needlework if they took cookery, dressmaking or laundry work.

Doris’s five art workbooks provide a fuller picture of the curriculum in practice in one subject. She took drawing between the ages of eleven and fourteen. Drawing was given enhanced status in the new syllabus and – fortunately for Doris – it was a priority both for the Wanganui Education Board and amongst local women teachers in particular. Towards the end of 1917, at the request of the Wanganui Teachers’ Association, the Board’s Supervisor presented a lecture on drawing that was attended by 50 Manawatū teachers.8

The following year a midwinter school of instruction in science and drawing was held, with the object mainly of qualifying untrained teachers in remote schools for a practical certificate in science. That year the Whanganui Inspector reported drawing to be ‘greatly improved, owing mainly to the untiring efforts of the Board’s special instructor, in whose methods teachers take a marked and profitable interest.’9

Yet, as Doris’s workbooks show, the implementation of such programmes was often based on a stilted and highly artificial conception of drawing. Doris was constrained by policy and pressure to do things the ‘correct’ way. Encouragement of free expression was not yet part of the teaching of art.

At the primary-school level, drawing was largely a training in exactness – especially for boys, for whom art was typically linked to science or technical subjects. Girls, it was widely believed, had neither the need nor the capacity for defining and drawing geometrical shapes. While progressivism encouraged creativity, the implementation of the subject reflected gendered beliefs. The teaching of art for girls all too often invoked traditional accomplishments.

Doris’s workbooks include examples of drawing from objects, shading, perspective, free-hand drawing – and geometric drawing. Doris began drawing to scale in Standard Four and moved on to drawing plans, elevations of plane figures and rectangular solids. Samples of cardboard work carried out over the three years include simple geometric solids. These show Doris’s expanding drawing, technical and arithmetical skills and the accuracy needed in such work. Her geometrical drawings show that gendered norms were not always upheld in practice.10

Doris’s interest in the subject is suggested by the care and attention shown in her work and the fact that she kept these books for the rest of her life. No matter how formal her art education may have been, it did not extinguish Doris’s interest in the visual arts. One 1918 workbook also includes work undertaken later that shows further experimentation with drawing techniques and illustrates Doris’s observational skills.

Nature study, another subject favoured for girls, was based on discovery through experiment. It was not a separate subject but schools were to introduce it into other subjects as appropriate. Rural schools undertook nature study alongside gardening. Doris’s nature study and drawing books show that the subject was taught through observation of the living world and by cultivating plots in the school garden.

A taste for home science was cultivated amongst all girls regardless of their academic interests. This subject had grown in significance as a means to extend the practical content of the curriculum and to apply scientific methods in response to the educational shift towards the practical impact of broader social issues on domestic health and well-being. Its focus on the teaching of life skills and the management of home and family provided a scientific underpinning for domesticity.

Doris took home science as a subject in Standard Five. Her workbook shows she received instruction that was both practical and to a lesser extent scientific. Exercises included practical instruction in starching, window cleaning, sweeping clean a grate, lighting a fire and cleaning a range, as well nutrition. The establishment of a daily routine was emphasised.

Keep the home tidy by arranging your work properly, so that apart from washing day and cleaning day, the greater part of the work is done before dinner.11

Doris’s notes appear to have been copied from the blackboard or a teacher’s notes. It is unknown if the skills taught were demonstrated or if students had the opportunity to practice them.

In the back cover of her exercise book and also in her autograph book, Doris’s predicted future is reinforced in a variation of a verse then popular in girls’ autograph books:

Doris Collins is your name,

Single is your station,

Happy is the man,

Who makes the alteration.12

Doris left school in 1918, seven months after reaching the legal leaving age of fourteen. Secondary schooling was not yet a common experience for most children. Boys from rural schools typically left to work on a farm or in a nearby town. Girls left to work at home in preparation for their future domestic roles as wife and mother. Few took on paid employment.13 With her mother dead and her sister no longer living at home, Doris was to care for her father and help out on the farm. The Awahuri School register records that she left for ‘Home Service’.14

A decade later, in February 1929, Doris married Stan Smith and continued her domestic role, as a wife and later a mother. While Stan worked as the Hardware Manager at Collinson and Sons, Broadway, Palmerston North for 37 years, Doris happily managed their home, which Stan had built. She is remembered as a highly competent ‘housewife’ who ran an orderly home. To what extent Doris’s schooling based around home-oriented subjects had prepared her for her future role in society is less certain.

Doris’s school artefacts serve both historical and cultural functions. Whether deliberately or by chance, some of her schoolbooks and the Christmas stocking remained safe in her care. The schoolbooks she kept had relevance for her adult domestic life. Her art classes taught her to look and to observe – traits she carried into her adult life. Her interest in art was expressed in adulthood through embroidery, her garden, and her award-winning floral arrangement work.15

These material sources are more than mere illustrations of schooling and childhood. Doris’s Christmas stocking and schoolbooks are pieces of history in their own right. They provide glimpses into the everyday gendered educational experiences of one child and broader social and cultural values underpinning prevailing beliefs about how children should be taught and what they should know.

First published in Fiona McKergow and Kerry Taylor, eds, Te Hao Nui – The Great Catch: Object Stories from Te Manawa, Random House, 2011; updated and republished with the author’s permission.

Footnotes

- School Registers, Palmerston North Genealogy Branch, New Zealand Society of Genealogists. ↩︎

- Manawatu Evening Standard, 14 Aug 1914, p. 1. ↩︎

- Ewing, Development of the New Zealand Primary School Curriculum 1877–1970, p. 12. See also Ruth Fry, It’s Different for Daughters. ↩︎

- Ewing, Development of the New Zealand Primary School Curriculum 1877–1970, p. 88. ↩︎

- Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives (AJHR), 1916, E-1A, p. 8. ↩︎

- Report of the Inspector of Manual Instruction, AJHR, 1916, E-2, p. 1. ↩︎

- Report of the Inspector of Manual Instruction, AJHR, 1916, E-2, p. 1. ↩︎

- Extract from the Report of the Director of Manual and Technical Instruction, AJHR, 1918, B-2, p. iv. ↩︎

- AJHR, 1919, E-2, p. vii. ↩︎

- Report of the Inspectors of Manual and Technical Instruction, AJHR, 1915, E-5, p. 11. ↩︎

- Exercise book with Home Science lessons, Awahuri School, 1917–18, donated by Natalie Townley, Te Manawa Museums Trust, 2009/16/12. ↩︎

- Autograph book, c. 1910s, donated by Natalie Townley, Te Manawa Museums Trust, 2009/16/14. ↩︎

- Hobbs, ‘The Kairanga’. ↩︎

- Awahuri School Register, 1918, Palmerston North Genealogy Branch, New Zealand Society of Genealogists. ↩︎

- For more on collecting childhood artefacts, see Townsend, ‘Seen But Not Heard?’, and for more on the material culture of Christmas, see Clarke, Holiday Seasons. ↩︎

Bibliography

Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives, 1915–1919.

Clarke, Alison, Holiday Seasons: Christmas, New Year and Easter in Nineteenth-Century New Zealand, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2007.

Ewing, John, Development of the New Zealand Primary School Curriculum 1877–1970, New Zealand Council for Educational Research, Wellington, 1970.

Fry, Ruth, It’s Different for Daughters: A History of the Curriculum for Girls in New Zealand Schools, 1900–1975, New Zealand Council for Educational Research, Wellington, 1985.

Hobbs, Patti, ‘The Kairanga’, Christchurch Teachers College research project, unpublished manuscript, 1940, Te Manawa Museum.

School Registers, Palmerston North branch of the New Zealand Society of Genealogists.

Townsend, Lynette, ‘Seen But Not Heard? Collecting the History of New Zealand Childhood’, MA thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, 2008.

Leave a comment