Sue Scheele

As a ‘baby-boomer’, one of my fond memories of early school days is of sitting on the classroom mat listening to the teacher read the afternoon story. However gripping the tale, I’d wriggle and squirm, trying to escape the hard, prickly mat fibres that reddened and dimpled my bottom, legs and hands. Little did I realise that the cause of my discomfort had contributed to the prosperity and identity of Manawatū for generations.

The colourful matting samples shown here were donated by Palmerston North Girls’ High School, and probably relate to refurbishment work at the school in the late 1950s and early 1960s – perhaps the building of the two-storied Mayhew Block. However, we can’t be sure what choice of floor-covering was finally made.

These carpets – ‘Brussella’, ‘Cordella’ and ‘Gayleen’ – were manufactured at the large New Zealand Woolpack and Textiles factory in Foxton from the mid-1950s. Their manufacture represented a diversification from the factory’s original purpose – making packs for exporting wool from harakeke, New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax), often referred to in the industry as phormium or hemp.

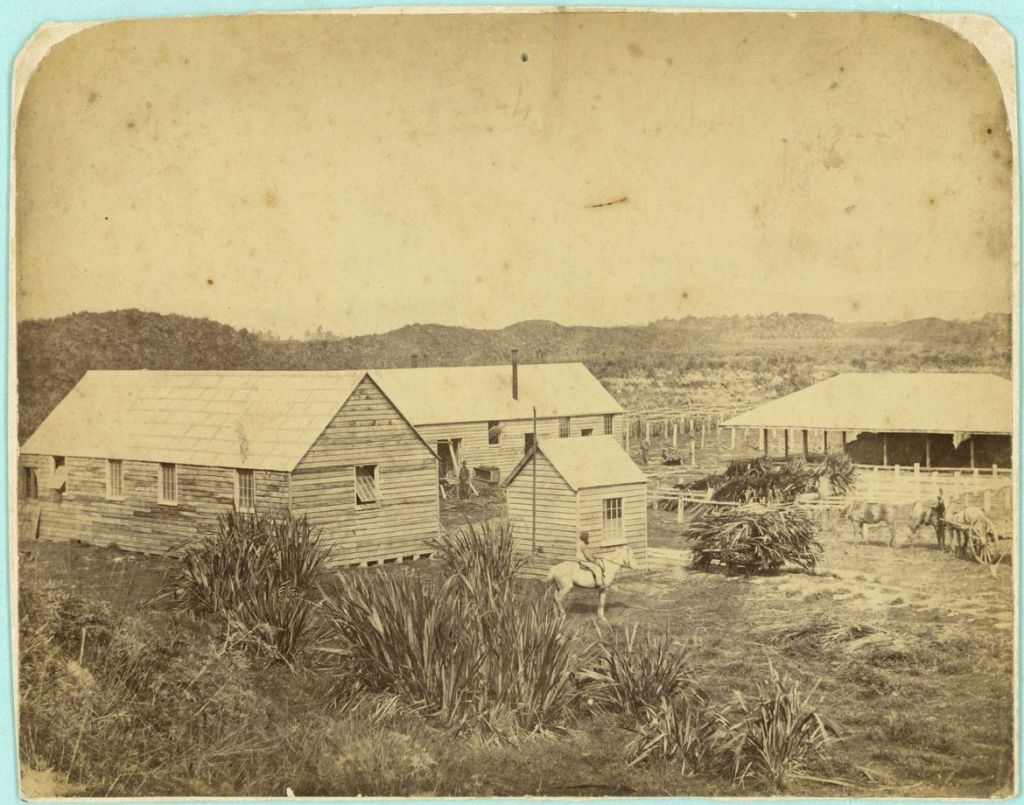

For 100 years, Foxton’s very existence revolved around growing, processing and manufacturing products from New Zealand flax.1 Flax once covered large areas of the Manawatū Plains, and until the 1970s the region was at the centre of New Zealand flax growing and the development of new processing technologies.

Europeans had been quick to recognize the value of the long, strong fibre they saw Māori prepare from flax leaves. Harakeke was a key plant in the Māori economy, with the leaves and extracted fibre providing containers, nets, cordage, matting and clothing. In the early decades of colonisation, tons of this natural resource, hand-extracted by Māori using shells, were exported to Sydney and Britain for to make ropes – an essential commodity in the era of sailing ships. In the late 1860s, machinery was developed to replicate the slow hand-extraction process, though with a much coarser result. The flax industry was under way.2

Wars were always profitable for phormium fibre producers, as they caused shortages of Manila hemp, sisal and jute – phormium’s rivals for cordage and coarse matting. The First World War saw great demand around the world for all fibres, and flax exports achieved their highest prices. After the war, prices slumped because other natural fibres were cheaper to produce in Asia, Africa and India. Then the world-wide economic depression of the 1930s saw overseas markets for phormium fibre collapse totally.3

The threat to Foxton’s economy was averted thanks to a new opportunity to utilise flax for the domestic market. Wool was New Zealand’s main income earner, and about 800,000 packs were needed each year to bale it for export. The New Zealand Woolpack and Textiles factory was built by the government in 1933 to produce packs to supplement the cheap jute bags imported from India. To help the supply chain, the government also bought the large Moutoa Estate, which had been producing flax for some 50 years. Rather than using natural stands of flax, the government planned to foster plantations to ensure the best quality of fibre. The state also subsidised the flax growers, millers and manufacturers, and restricted imports of cheap jute bags.4

Two factors constrained the economic success of the venture. In the factory, shortage of reliable labour was a constant complaint from management. Wages were reasonable, but much of the work was monotonous and the machinery was extremely noisy. One-third of the 200 staff in the Foxton factory were women, who were employed solely in the weaving and sewing departments. Good workers were lost to a clothing manufacturer down the road; sewing fashion garments was more appealing than sewing woolpacks. Māori staff in particular had family connections and responsibilities that called them away to seasonal work in shearing gangs or the freezing works.

After the Second World War, management took various initiatives to attract and retain staff. State houses were built and loans advanced to lure families to Foxton;5 a hostel was opened to accommodate young Māori female employees;6 loudspeakers were installed to play music to relieve the monotony of repetitive work (despite the director finding the ‘music’ a ‘screaming annoyance’).7 Radio appeals were made for weavers, and in 1956, with a view to making weavers the ‘aristocrats’ of the industry, and to encourage learners, the starting rate for girls was lifted by 15s (worth about $47 in 2024) a week.8 That year managers also proposed establishing a crèche at the factory to care for young children of employees ‘in pleasant surroundings for a nominal charge’;9 it perhaps reflects the social mores of the time that there was insufficient interest for this plan to proceed.

Another limiting factor was a shortage of supplies of green flax, the raw material. Although plantations were being planted at Moutoa, these never produced enough good-quality flax. John Gailey, an Irishman with an extensive knowledge of the textile industry, had been brought to New Zealand before the war to advise on improving the industry. He advocated the development of supplies of good flax and the diversification of the products made.10 On a return visit in 1950 Gailey was ‘depressed’ at the lack of green leaf available. He re-emphasised that phormium yarn was too valuable to put into woolpacks; its use in matting should be increased.11

New Zealand Woolpack and Textiles was already producing flax matting in a variety of patterns (the designs were advertised as of European and Māori influence) for use as hall runners, large squares (‘for the sunroom’), and smaller mats. Shaped mats were manufactured for the most popular makes of car. The downside was a poor dyeing process. The matting faded and became drab far too quickly – and it was not waterproof.12

The gaily coloured carpet samples pictured above show how far the company was prepared to go to improve manufacturing processes and diversify. The patterns and colours reflect a modern, clean 1950s look. In this era kitchen and living areas were commonly linked in new houses, and formal lounges with heavily-patterned floral or embossed carpets became unfashionable.13

New Zealand Woolpack and Textiles researched and invested in a new process for dyeing individual slivers of flax fibre (rather than just coating the spun threads) which prevented premature fading. New weaves with different weights and twists included herringbone twill and the Brussels weave (a low loop pile). New patterns were designed to give customers more choice of ‘modern floor coverings for modern homes’.14

The ‘Brussella’ range of loop pile carpeting became very popular. This was made of a blend of specially selected strong flax fibre with 15 per cent rayon (derived from wood pulp) for softness. Brussella was reversible and woven in plain shades for wall-to-wall laying. Its hard-wearing qualities made it suitable for commercial as well as domestic environments. After it was laid in Wellington Airport’s new terminal, a newspaper advertisement in 1962 proudly proclaimed: ‘YES – nearly 10 Million Feet have trodden on the hardest wearing carpet in history’.

The company also launched an improved ‘Cordella’ range of floor-covering. This was made from imported sisal, the former rival of phormium fibre. Sisal was chosen for its cheapness and because as a naturally whiter fibre it could take up light-coloured dyes. Its attractive sheen when newly manufactured made a good impression on customers. Hard-wearing, it was sold as rugs and squares for ‘brightening up drab corners, top o’ stairs, and entrance-ways too’.

The other ‘flax’ floor-covering , produced as a broadloom carpet, was ‘Gayleen’ – 100 per cent rayon, finer and softer than phormium. The yarns were twisted together to give ‘Gayleen’ a rippled or ‘willowbark’ effect, as well as plain colours with light flecking.15

All these floor-coverings were widely marketed through the press and radio, window displays in retail stores, and stands at provincial A&P shows. In 1958, the carpets featured on a float in the Hastings Blossom Festival seen by ‘a crowd of 80,000’, and they were enthusiastically endorsed on the radio by ‘Aunt Daisy’ after she visited the factory.16 They sold well domestically and were exported to Australia and Canada.17

But the writing was on the wall for the flax industry. The 1960s saw the rise of synthetics and increased grumbling from farmers who resented paying higher prices for woolpacks ‘to keep a few people in employment’.18 Subsidies on flax production were removed in the early 1970s. New Zealand Woolpack and Textiles experimented with the new synthetic products, producing a fully synthetic woolpack and ‘Duramat’, a colour-fast matting impervious to water made from extruded PVC tubing with polyethylene weft. ‘Duramat’ was promoted for use in kitchens, bathrooms, outdoor areas, boats and caravans – ‘in fact, there are unlimited imaginative possibilities for its use’.19

Even with these innovations, New Zealand Woolpack and Textiles could not compete with lower production costs overseas for synthetics and the factory was sold to a carpet manufacturer in 1972.20 A subsidiary company, Bonded Felts, bought one of the strippers and the remaining flax supplies and continued to use flax in upholstery and twine until the mid-1980s, when the factory burnt down. A mainstay of Manawatū’s economy for so long, the flax era was over.

First published in Fiona McKergow and Kerry Taylor, eds, Te Hao Nui – The Great Catch: Object Stories from Te Manawa, Random House, 2011; updated and republished with the author’s permission.

Dedication

This article is dedicated to the memory of Ian Matheson, a former Palmerston North City Archivist, whose extensive research on the Manawatū flax industry has left a wealth of resources for those who follow.

Footnotes

- Kirkland, ‘The Challenge of Flax’; Hunt, ‘Foxton’s Flax Industry’, pp. 36–7. ↩︎

- Hector, Phormium Tenax as a Fibrous Plant. ↩︎

- Sparrow, ‘The Growth and Status of the Phormium Tenax Industry of New Zealand’, pp. 331–45. ↩︎

- Minutes of Cabinet sub-committee on matters affecting the flax industry and the manufacture of woolpacks. February 1939, file ICI 1 7/2/2/ part 1, ‘Flax stripping methods’, Archives New Zealand, Wellington (ANZ). ↩︎

- NZ Woolpack & Textiles Ltd company minutes, Managing Director’s reports, various, March 1951–February 1954. ↩︎

- NZ Woolpack & Textiles Ltd company minutes, Managing Director’s report, 30 April 1947. ↩︎

- NZ Woolpack & Textiles Ltd company minutes, Managing Director’s report, 25 May 1945. ↩︎

- NZ Woolpack & Textiles Ltd company minutes, Management report, Agenda item 11, 18 May 1956. ↩︎

- NZ Woolpack & Textiles Ltd company minutes, Management report, Agenda item 8, 8 March 1957. ↩︎

- Minutes of Cabinet sub-committee on matters affecting the flax industry and the manufacture of woolpacks. February 1939, file ICI 1 7/2/2/ part 1, ‘Flax stripping methods’, ANZ. ↩︎

- NZ Woolpack & Textiles Ltd company minutes, Summary of Mr Gailey’s verbal report to the Board and following discussion, 9 August 1950. ↩︎

- NZ Woolpack & Textiles Ltd company minutes, Report on arrangements for matting distribution, Agenda item 9, 28 August 1950. ↩︎

- Lloyd Jenkins, At Home: A Century of New Zealand Design, p. 126. ↩︎

- NZ Woolpack & Textiles Ltd company minutes, Management report, Agenda item 13(2), October 1954. ↩︎

- Typed notes in Charles Anderson folder, I.R. Matheson Papers, Series 3/1, Box 2. ↩︎

- NZ Woolpack & Textiles Ltd company minutes, Board meeting, Agenda item 7, 24 September 1958. ↩︎

- NZ Woolpack & Textiles Ltd company minutes, Management reports for period 1954–1970. ↩︎

- ‘Ransom to Keep Flax Mill Going’, Levin Chronicle, 23 June 1970, I.R. Matheson Papers Series 3/3, Box 3. ↩︎

- Typed notes in Charles Anderson folder, I.R. Matheson Papers, Series 3/1, Box 2. ↩︎

- NZ Woolpack & Textiles Ltd company minutes, Management reports for period 1970–1972, PNCA. ↩︎

Bibliography

Hector, J., ed., Phormium Tenax as a Fibrous Plant, 2nd edition, Government Printer, Wellington, 1889.

Hunt, T., ‘Foxton’s Flax Industry’, New Zealand Historic Places, no. 46, 1994, pp. 36–7.

Kirkland, Graeme James, ‘The Challenge of Flax: A Study of New Zealand Woolpack and Textiles Limited, Foxton, and its Employees’, MA thesis, Massey University, 1970.

Lloyd Jenkins, Douglas, At Home: A Century of New Zealand Design, Random House, Auckland, 2004.

Matheson Papers, Flax Files, Series 3/1, Box 2, Palmerston North Community Archive.

Matheson Papers, Flax: NZ Woolpack and Textiles Ltd, 1870s-2002, Series 3/3, Palmerston North Community Archive.

Sparrow, C.J., ‘The Growth and Status of the Phormium Tenax Industry of New Zealand’, Economic Geography, 41, 1965, pp. 331–45.

Leave a comment