Russell Poole

‘To Make the Puzzle is to Learn the Empire’

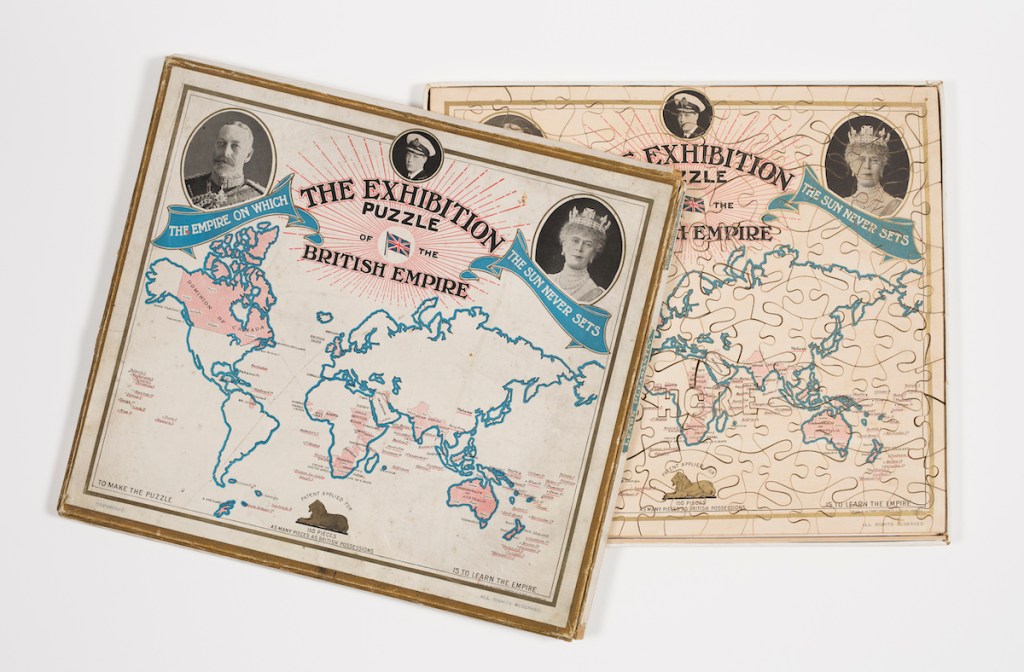

The ‘Exhibition Puzzle of the British Empire’ is a modest-looking but fascinating item in Te Manawa’s collection.

It has been on show in three different exhibitions since its acquisition in 1975. The rest of the time it sits in Te Manawa’s storeroom.

Collections manager Cindy Lilburn led me through the labyrinthine passageways to the storeroom, issued me with gloves and unpacked the puzzle. She also gave me some basic information about the puzzle and its donor that have served as clues towards my investigation.

To solve the riddles of the puzzle I am going to follow three different lines of investigation in three different parts, or ‘threads’.

This thread is about the puzzle itself, as a fine example of jigsaw craft. We’ll also enquire into its mysterious creator, Mr Dick Shore.

Measuring 300mm x 340mm x 5mm, the British Empire Exhibition jigsaw puzzle has 150 pieces, packed in a cardboard box.

Remarkably, this 100-year-old puzzle is complete, with no pieces missing.1 It might be one of very few copies left in the world.

It’s not too hard a puzzle by today’s standards. As you solve it you can refer to the lid of the box, which shows how the finished puzzle should look.

Puzzle-makers a hundred years ago, when this one was manufactured, tended to avoid putting a picture on the lid. They didn’t want to make the solver’s task too easy.

Also making the solver’s task fairly easy is the fact that the pieces of our puzzle are quite large. The shapes are distinctive. There is plenty of lettering to guide you on where to place the pieces – though you do need good close eyesight!

The puzzle has an educational purpose: ‘To make the puzzle is to learn the Empire,’ it says. It aims to teach the solver the location of all the territories that belong within the Empire. That could sound quite demanding.

But it also says, ‘Learn Pleasantly’ – Meaning that the maker wanted the puzzle to be easy and fun to solve, so that you’d learn the locations of the different countries effortlessly.

Although teachers in the schools of one hundred years ago could undeniably be strict, a feeling was developing that education ought to involve play and enjoyment and pleasure and kindness. My mother, aged eight at the time of the British Empire Exhibition and with a paralysed right leg, recalled the headmaster of Invercargill South School hoisting her up on to his shoulders and piggy-backing her round the playground!

The person who devised the puzzle is identified as ‘Dick Shore inventor’.

Also, we see that the British Empire Exhibition commissioned it from a firm called the Thames Engraving Company. Their office and workshop had its address at 111 Shoe Lane, London EC.2

You could walk to Shoe Lane from St Paul’s Cathedral, the heart of the British Empire, in about fifteen minutes. What you would have found one hundred years ago was a rabbit warren of little printing, engraving and commercial art premises.

So far I have not succeeded in tracing either Mr Shore or the company. That may suggest that the company was short-lived and Mr Shore sought other pursuits, perhaps far away from Shoe Lane. He may have been from the US or Canada. Can you do better than me in tracking him down?

Whatever his identity, we can see, looking closely at the puzzle, what an ingenious fellow Dick Shore was.

For instance, why the total of 150 pieces? (If you’re unsure, you’ll find the answer at the bottom of the page.)

You’ll see another instance of his ingenuity if you look closely at the pieces.

Most of them are incised in sweeping curves. The exception is the nine pieces spelling out the name ‘Dick Shore’, seen in reverse below. These are extra to the count of 150 pieces.

In my experience as a jigsaw solver, it’s highly unusual to see the puzzle-maker’s name embedded in the puzzle in this way. Usually there’s just an artist’s signature written or painted near the bottom.

Dick Shore, besides calling himself the ‘inventor’, states that a patent has been applied for. What’s the significance of that?

Patents are only granted for original inventions. To qualify for a patent, Dick Shore would have had to come up with something completely new in puzzle wizardry. It would have meant a lot of money for him had he been successful, since only he would have had the rights to manufacture a puzzle using his new concept.

The concept of turning a map into a puzzle is not something he could have sought to patent. That was a very old idea. It goes back to an eighteenth-century English tradesmen called John Spilsbury.3

Spilsbury’s concept was to mount a paper map of the world on wood and then cut out the countries with a small saw. China, India, Germany, France, and so forth each became a separate piece. Probably the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans were just one large piece, it would be too difficult to cut out all the islands as separate pieces!

Teachers could then scatter the pieces on a desk and task the class with re-assembling them. After you’d gone wrong by placing Spain next to Germany once or twice you’d remember that actually it belongs next to France and Portugal!

So the map concept was old. Too old for Dick Shore to hope to gain a patent for it. His application must have related to some other aspect of the puzzle. Could it have been the technique used to cut the pieces?

We talk of ‘jigsaw’ puzzles, from the type of saw that started to be used in the 1880s to cut the pieces. But do you think Dick Shore used a saw to cut this puzzle? Look at the photos closely.

It would be a fiddly job, especially the small letters. There’d be every chance of leaving rough edges or tearing the paper.

Instead I think he used a device like a cookie cutter, with very sharp edges. Or, more precisely, like 159 small cookie cutters assembled within a metal grid.

Each ‘cookie cutter’ would be in the shape of one of the pieces of the puzzle.

The grid would be placed over the thin plywood and clamped down tight. This would force the sharp edges right through the plywood, stamping out the pieces.4

But this cookie-cutter device had been invented before Dick Shore came along. He couldn’t expect to get a patent for it.

More likely what Dick Shore wanted to patent was the concept of including small letters spelling his name.

Unfortunately for him, here too ‘prior art’ existed. In other words, some earlier puzzle-maker had been granted a patent for essentially the same idea. This lucky inventor was Theodore Bamberg, who was granted an American patent for small letter pieces in 1917, just seven years earlier than our friend Dick Shore. The patent number is US1256100A and you can find it online at Google Patents.

The Patent Office will have noted Mr Bamberg’s prior art and declined Dick Shore’s application. No particular disgrace – this happens to would-be inventors all the time! Even Thomas Alva Edison, one of the most successful inventors in history, had to fight to retain his patent (US223898) for the electric light bulb.5

Answer

Because 150 was the number of recognised British possessions in 1924.

First published by Te Manawa on 20 February 2023; updated and republished with the author’s permission.

Footnotes

- For a description of another copy of this puzzle, albeit in inferior condition, held by the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, see https://collection.maas.museum/object/167160 ↩︎

- For the story of Shoe Lane, which has nothing to do with shoes but takes us deep into medieval London, see Jenstead ‘Shoe Lane’. ↩︎

- Norgate, ‘Cutting Borders’, pp. 342–43; Pepe, ‘Dissected Maps’. ↩︎

- Bob Hodgson and Philip Poole are my informants here. What I’ve called a ‘grid’ could alternatively be called a ‘template’. ↩︎

- Peterson and McKelvie, ‘Who invented the light bulb?’. ↩︎

Bibliography

Jenstad, Janelle, ‘Shoe Lane’, The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0, Janelle Jenstad, ed., University of Victoria, 05 May 2022, URL: https://mapoflondon.uvic.ca/SHOE1.htm, accessed 27 August 2024.

Norgate, Martin, ‘Cutting Borders: Dissected Maps and the Origins of the Jigsaw Puzzle’, The Cartographic Journal, vol. 44, no. 4, 2007, pp. 342–50. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1179/000870407X241908

Pepe, Amy, ‘Dissected Maps: The origins of jigsaw puzzles’, Historic Geneva, 27 March 2020, URL: https://historicgeneva.org/recreation/dissected-maps/, accessed 27 August 2024.

Peterson, Elizabeth, and Callum McKelvie, ‘Who invented the lightbulb?’, LiveScience, 3 November 2022, URL: livescience.com/43424-who-invented-the-light-bulb.html, accessed 27 August 2024.

Leave a comment