Russell Poole

The British Empire Exhibition, 1924–25

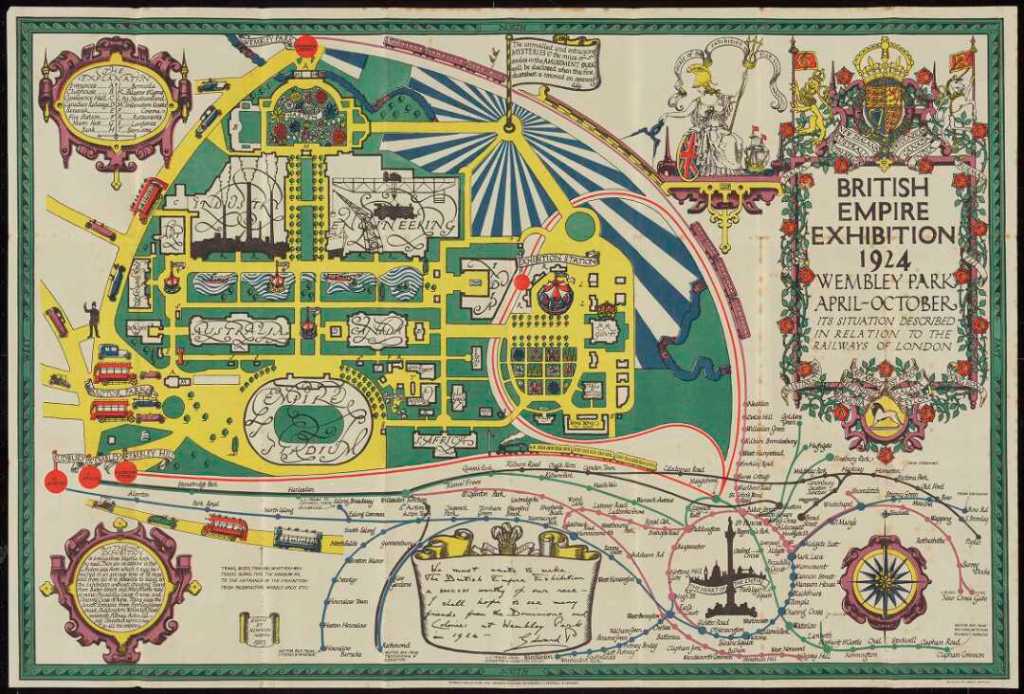

Lenora Coldstream’s puzzle would originally have been bought by somebody attending the British Empire Exhibition. What did this Exhibition consist of?

Set in the London suburb of Wembley, where football’s famous Wembley Stadium now stands, the Exhibition spread over 220 acres (just short of 90 hectares). That’s more than twice the size of Disneyland and fifteen times the size of Palmerston North’s Square / Te Marae o Hine.

That huge space made ample room for commercial, technological and artistic displays, national pavilions, an artificial lake, and restaurants, cinemas and an amusement park.

People in Britain needed amusement and cheering up at that time. The dreadful losses and the chaos of the First World War still haunted most people.

The Exhibition lasted through 1924 and 1925. It attracted approximately 25,000,000 visitors. At the time London had a population of roughly 7,400,000.

The organisers emphasised the educational benefits the Exhibition held for children and working-class families. They claimed that visitors learnt more about the Empire in a few days than they might after months of actual travel through the Empire’s possessions.1

Naturally New Zealand had its own pavilion, albeit tucked in near the boundary and dwarfed by Australia and Canada. We had some great exhibits to show off! They included a reconstruction of a moa.

Sisters Martha and Piki-te-ora Ratana represented te ao Māori.2 Here we see them at Whanganui on 7 May 1924 shortly before they sailed to England for the Exhibition. They are wearing kahu kiwi and holding mere.

Carpenter and luthier James Williamson displayed some of his violins and won an award. Originally from Shetland, Williamson started his career in Mākōtuku and Feilding. He described his violins as made on the ‘Feilding model’.3

Purchasers of a pound of butter from the New Zealand pavilion were given ‘a pretty little butter knife with a New Zealand inscription’, a proud reference to our biggest export.4

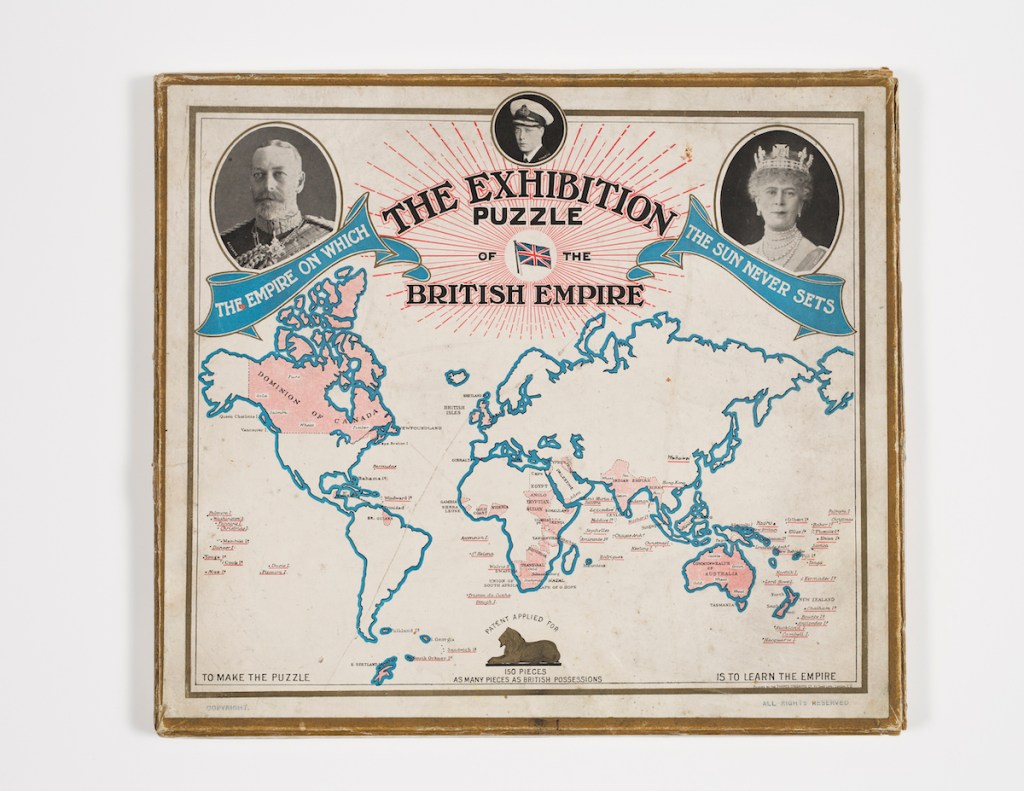

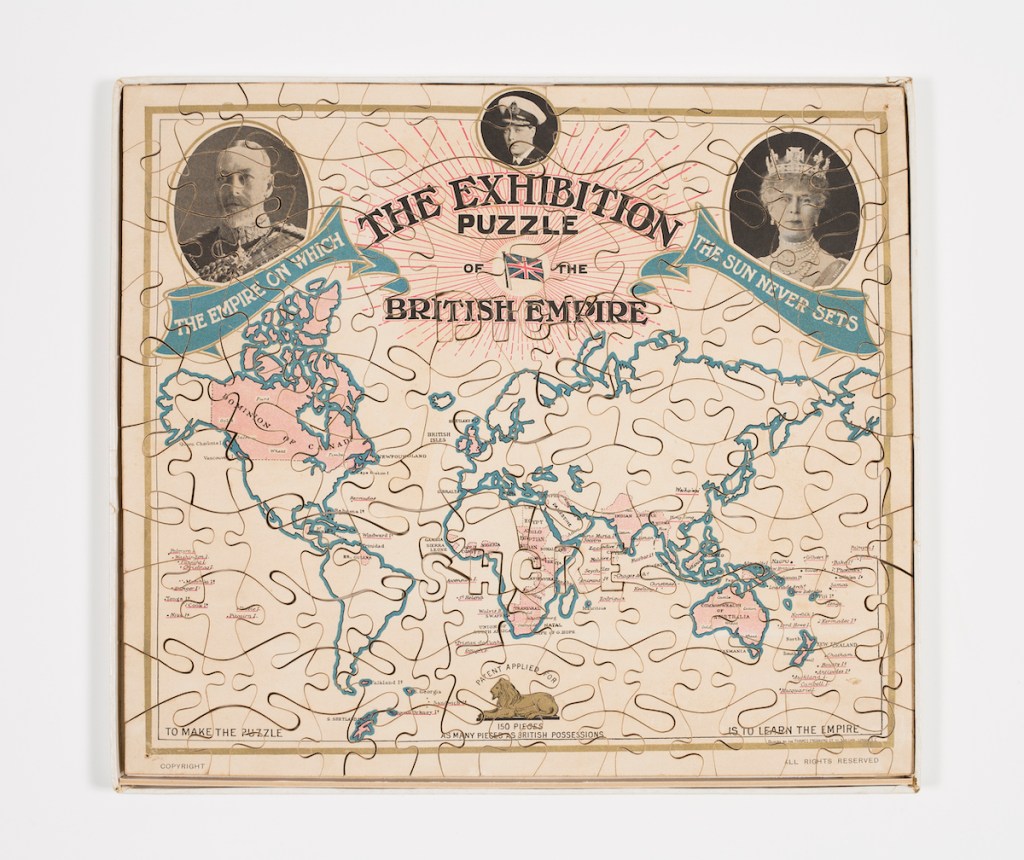

Examining the Puzzle

Let’s now get out our virtual magnifying glasses and take a close look at the puzzle.

We’ll start at the top. The two larger photographs at either side show King George V and Queen Mary respectively. These cameo portraits were taken by society photographer Alexander Bassano. You can see his surname to one side of the cameos. He occupied a ‘grand studio’ in Bond Street – an altogether smarter part of London than Dick Shore’s Shoe Lane!

But Bassano’s studio also took photos of ordinary people, including nurses and wounded soldiers in the First World War shown in the photograph below.

Between the King and Queen, in a smaller cameo, you see a man wearing a cap. He looks like a captain but actually he is Prince Edward, son of the king and queen. He was Prince of Wales at the time, just as Prince William is now.

Edward was king for slightly less than a year after George’s death in 1936. He actually gave up the throne – but that’s a story for another day.

The name ‘Vandyk’ in Edward’s cameo denotes the photographer Carl Vandyk. From 1882 he owned a studio at Gloucester Road in London. Like Bassano, he took photos of the British royal family.

His company merged with Bassano’s in the 1930s to form what became ‘the’ photographic studio for top people in British society.

The lettering at the top of the puzzle states proudly that the sun never sets on the British Empire. This was literally true, since the Empire had possessions right round the globe, covering just about all time zones.

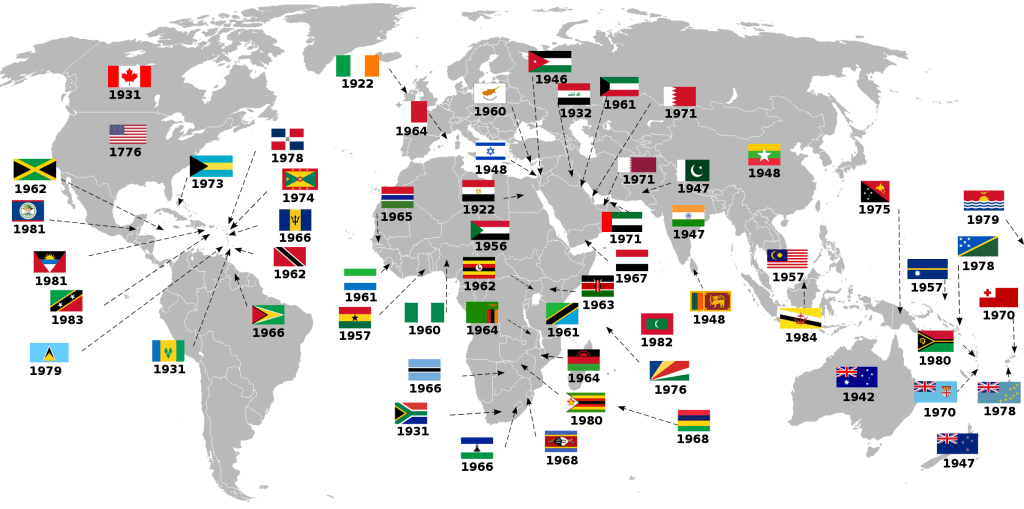

But it’s not true in the figurative sense, since the Empire did indeed have its sunset.

Historians argue about precisely when that sunset occurred: When India received its independence in 1947? When British possessions in Africa were decolonised in the 1960s? When Hongkong was returned to China in 1997?

If you or your family come from a former British Empire possession, you will likely know the date on which your country became independent.

At the base of the puzzle is a lion. This large fierce feline is the symbol of Britain and the Empire and also the logo for the British Empire Exhibition.

In the map, the possessions of the British Empire are picked out in red. Some possessions are mere specks of islands, making it not difficult to arrive at the tally of 150.

The map is centred on Britain. From our point of view in Aotearoa, it’s nice that it has been designed so that we and Australia are grouped together. On many other world maps of the time our two countries are shown at the extreme right and left respectively. Worse still, on some maps New Zealand disappears altogether!

Canada and Australia are referred to by grand titles: ‘the Dominion of Canada’ and ‘the Commonwealth of Australia’. Even though the map doesn’t say so, New Zealand was another dominion. It gained that status in 1907, along with Canada, Newfoundland, Cape Colony, Natal and Transvaal.

The then prime minister of New Zealand, Sir Joseph Ward, liked the term ‘dominion’ because he thought it would remind the world that New Zealand was not part of Australia. (This is a problem that Aotearoa still has today.)

But most New Zealanders back in 1907 weren’t aware that their country had suddenly become a dominion – and didn’t care. Equally, hardly anyone noticed when the title ‘Dominion’ was quietly dropped again in 1945, the year New Zealand joined the United Nations.5

Canada and Australia probably get extra attention in the puzzle because their landmass is big enough to accommodate extra lettering. Some of their leading products are also mentioned.

New Zealand has only one product cited, namely ‘meat’. This word is placed off the east coast of Te Wai Pounamu / the South Island, close to the location where the first frozen meat was shipped to England.

Some features that could be shown on larger world maps are omitted on Dick Shore’s map, for instance the sailing or aeroplane routes between countries, the latitudes and longitudes, and the equator and the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn.

All the same, a wealth of information finds its way in.

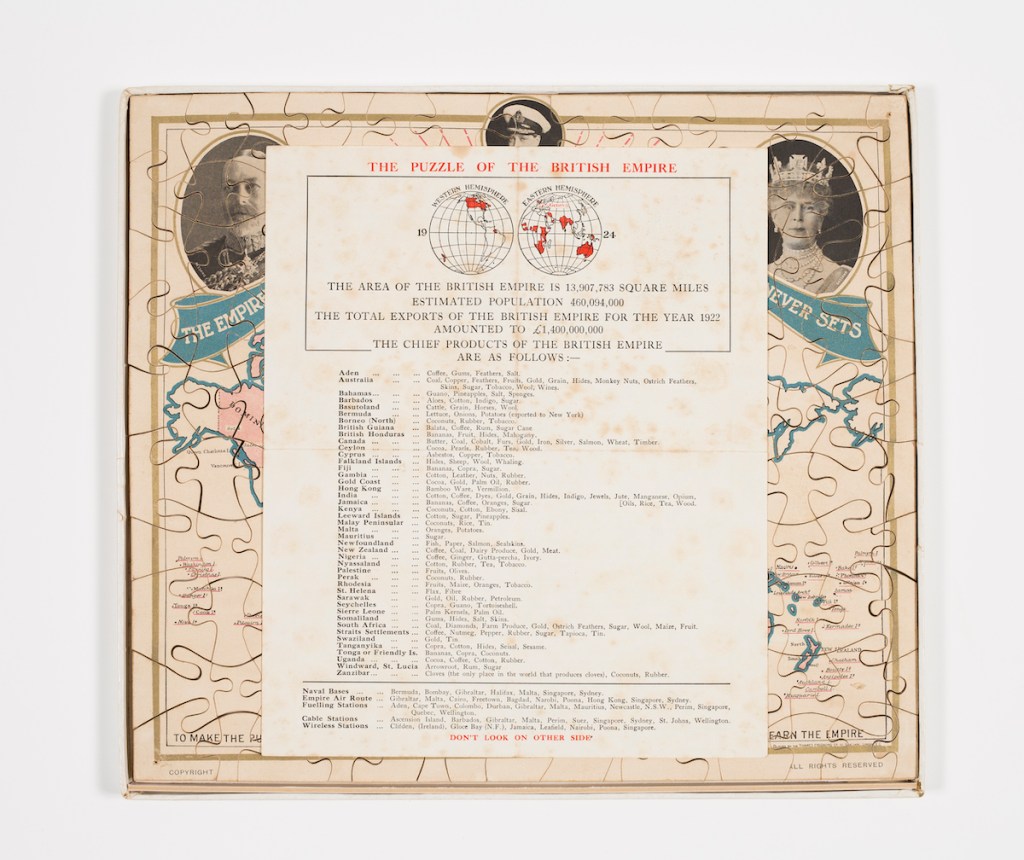

But clearly Dick Shore still wasn’t satisfied. If children were really going to ‘learn the Empire’ they needed to take in yet more information. So a paper insert was slipped into the box with the puzzle.

The front side of this paper insert tells you about:

- The area of the British Empire

- The total population of the British Empire

- The total exports of the British Empire for 1922

- The chief products of the British Empire, listed country by country.

If your family comes from India, you’ll see that a very large number of products were exported from there to Britain in 1922: cotton, coffee, dyes, gold, grain, hides, indigo, jewels, jute, manganese, opium, oils, rice, tea, wood. Do any of the products surprise you?

If you’re from Nigeria, it’s coffee, ginger, gutta-percha and ivory. What’s a major product nowadays that doesn’t make it on to the list?

Listed for New Zealand are the following export products: coffee, coal, dairy produce, gold, meat.

Question 1: What’s the odd one out here? (Answer below.)

We weren’t growing, let alone exporting, coffee in 1922. Yes, nowadays producers are experimenting with growing coffee plants in Northland, and tea in Waikato.

Who knows, one day, with climate change, tea and coffee might gain prominence among our export products? Few would have predicted that back in 1924. And yet the first newspaper article in New Zealand about human-induced climate change was published 13 years earlier in 1911.6

So how did coffee get on to our list of products? What do you think? Could it have been put in by mistake when really it belongs with the products of Nigeria (one line down)?

Question 2: What’s missing from our list of export products? (Answer below.)

Easy to overlook wool nowadays! Back in 1922, however, it was amongst this country’s leading products. It earned us £11,051,952. We were said to be living off the sheep’s back!

Only dairy produce (butter, cheese) earned us more, at £14,083,114. Frozen meat came in third, at £10,333,536. Coal and gold lagged far behind.7

So although the puzzle wants you to learn about the Empire, it got a few things wrong relating to New Zealand.

At the bottom of the sheet are lists of:

- Naval Bases (none in New Zealand)

- Empire Air Routes (none in New Zealand but impressive that any existed anywhere, considering that the aeroplane had been invented only 21 years earlier)

- Fuelling Stations (one at Wellington)

- Cable Stations (one at Wellington)

- Wireless (i.e., radio) Stations (none in New Zealand)

This sheet of paper says at the bottom: ‘Don’t look on other side.’

Let’s be disobedient and take a look!

The reverse of the insert contains yet more informative and educational material. Picture yourself in school back in the 1920s. Your assignment is to rote-learn all the following:

- Lists of the territories ceded by the German and the Ottoman Empires under provisions of the newly-founded League of Nations (1919). New Zealand gained Samoa – to see what resulted from that you can read this article.

- Information about the League of Nations and its constituent nations. New Zealand is on the list – not in its own right, though, but under the British Empire. That was the catch about being a dominion; it sounds grand but didn’t actually make you independent.

- A list of the chief ports of the British Empire. Wellington is included.

- Lists relating to shipping and shipbuilding in the British Empire.

- The deepest spot in the ocean; the highest mountain; the highest tide; average rainfall in Great Britain.

Answers

Question 1: Coffee

Question 2: Wool

First published by Te Manawa on 20 February 2023; updated and republished with the author’s permission.

Footnotes

- Clendinning, ‘On the British Empire Exhibition, 1924-25’. ↩︎

- Ballara, ‘Hura, Maata Te Reo’. ↩︎

- Poole, ‘Tailpiece’, p. 84. ↩︎

- ‘New Zealand Pavilion’, Auckland Star, 17 August 1925, p. 12. For a picture, see also https://oldcopper.org/special_topics/wembley%20exhibition_1924-26.php ↩︎

- ‘Dominion status – what changed? NZHistory, https://nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/dominion-day/what-changed, accessed 27 August 2024. ↩︎

- ‘Coal and the Atmosphere’, Rodney and Otamatea Times, Waitemata and Kaipara Gazette, 31 May 1911, p. 7. ↩︎

- See New Zealand Official Yearbook, 1921–22. These yearbooks are a wonderful online resource on all sorts of topics to do with Aotearoa. ↩︎

Bibliography

Arnett, George, Every country that has left the United Kingdom’s rule – in maps’, Guardian, 19 September 2014, URL: https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/gallery/2014/sep/19/every-single-country-that-has-left-the-united-kingdom-mapped, accessed 15 March 2022.

Ballara, Angela, ‘Hura, Maata Te Reo’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 2000, updated March, 2010. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, URL: https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/5h44/hura-maata-te-reo, accessed 27 August 2024.

Clendinning, Anne, ‘On the British Empire Exhibition, 1924-25’, in Dino Franco Felluga, ed., BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History, extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net, URL: http://www.branchcollective.org, accessed 15 March 2022.

New Zealand Official Yearbook, 1921–22, URL: https://www3.stats.govt.nz/new_zealand_official_yearbooks/1921-22/nzoyb_1921-22.html, accessed 15 March 2022.

Poole, Russell, ‘Tailpiece’, Manawatū Journal of History, no. 17, 2021, p. 84.

Leave a comment