Tony Rasmussen

Within Te Manawa’s collection is a simple, homemade Noah’s ark playset. The ark consists of a flat-bottomed hull with curved sides and square ends. It has a simple box-like cabin with a gabled red roof that can be removed to hold the nine animals in a menagerie. Each are two-dimensional, cut from the same material as the ark, using what looks like plywood or fretwood. Each animal is glued to a base and individually painted.

In some respects the set defies the conventions of Noah’s ark toys. There are no pairs, making each animal unique, and no human figures accompany the ark. The animals appear to be a camel, tiger, elephant, lion, bison (or water buffalo), goat, kangaroo, cow and turkey, with exotic animals in the majority. Introduced animals like the goat, cow and turkey give the set something of a New Zealand flavour, while the kangaroo is obviously Australian.

About the time the set was made, New Zealanders had spent several years enduring the economic and social hardships of the Great Depression of the 1930s. People were turning their hands to making many of their own toys and amusements. Even though these animals appear to have been made from a pattern, a certain level of skill and patience was needed to cut out, assemble and paint them. Perhaps the maker followed a set of instructions like those that appeared in the Wanganui Chronicle in December 1930:

HOW TO MAKE SOME XMAS NOVELTIES

Wooden Toy Animals

It is surprising what a large number of quaint birds and other animals can be cut out of fretwood and made to look quite realistic with a little paint, carefully applied. For instance the little goose and duck shown in the diagrams can be cut out of three-sixteenth wood and bases a half inch wide to allow them to stand up. … Other birds and animals will readily suggest themselves for cutting out in the same way, and if a number are made in pairs they will amuse your children for hours, especially if a toy Noah’s Ark is provided at the same time.1

If these instructions are anything like those used by the maker, they explain why the set has a partial farm-like feel compared to a standard Noah’s ark animal collection. Even so, one gets the impression that a great deal of love has gone into making this little set, and lots of fun was had in selecting which animals ought to be represented.

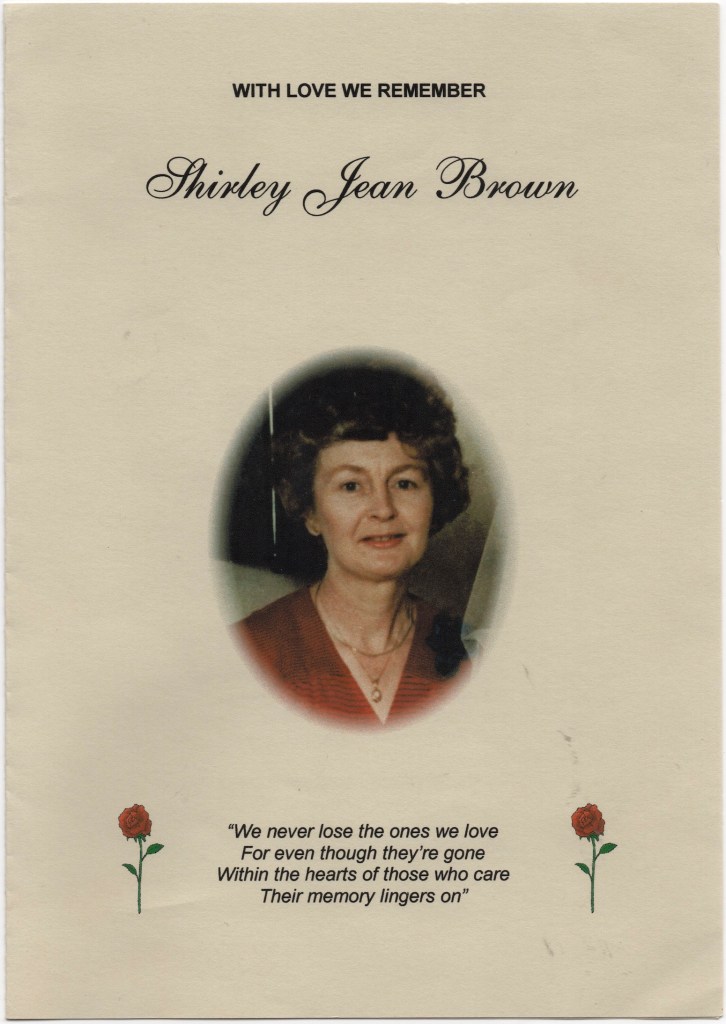

The playset belonged to Shirley Brown (1932–2000) of Makerua, a picturesque rural locality between Tokomaru and Shannon, at the edge of what was once the vast Makurerua swampland. While her parents farmed, Shirley and her brother Henry attended Makerua School, which existed from 1911 to 1974. Shirley’s love of animals was apparent when, aged 8, she won the prize for ‘best lamb’ at the nearby Shannon School’s 50th jubilee celebrations in December 1940.2[ii] Shirley attended Palmerston North Girls’ High School (PNGHS), after which she worked on the family farm and cared for her aging parents. Both Shirley and her father were active on the Makerua School Committee.

Following her father’s death in 1980, Shirley moved to Palmerston North with her mother. She worked for Moxon Jewellers, then the Palmerston North branch of the Inland Revenue Department, where she was a loyal employee for the rest of her working life. Following Shirley’s death from cancer in 2000, two collections of personal belongings were donated to Te Manawa by her friend Annette Nixon. One collection consisted of children’s books, work clothes and accessories, and the other was entirely children’s toys. Finding a Noah’s ark set among these is unsurprising as the Browns were a committed, church-going family at St David’s Presbyterian Church in Shannon. We cannot be sure who made it, although Annette Nixon suggests it was probably made for Shirley by a relative.

Noah’s arks were a staple toy for many children of church-going parents. At a time of strict Sabbatarianism, Noah’s arks are said to have been the only toy many children were permitted to play with on Sundays. In doing so, children were recreating the biblical story of Noah, who was entrusted with building an ‘ark’ (literally a vessel) large enough to accommodate pairs of every animal while the earth was covered by a gigantic flood. The inclusion of a construction account within the narrative has inspired many built variations of the ark, but toys have proved one of the most enduring ways to reimagine the biblical story.

In her investigation of a 19th century Noah’s ark at Te Papa, historian Lynette Townsend drew attention to the crafting of these toys as a significant cottage industry that emerged among impoverished villagers of the Erzgebirge Mountains in Germany. She explains the difficult conditions under which entire families laboured to produce beautifully crafted wooden sets, using processes from cutting to painting, that led to the establishment of a ‘worldwide centre’ for mass-produced Noah’s arks from the 1840s.3 Plastic Noah’s ark sets from the second half of the 20th century are also collectible today.

At the end of her life Shirley lived at Linville Rest Home, Weston Avenue, Palmerston North and attended St David’s Presbyterian Church at Terrace End. Shirley’s retention of the Noah’s ark and other toys signify their significance in her early life. Her love of reading is evident in the children’s books she kept. Some were awarded as prizes at Makerua School and PNGHS, while religious titles include Bible Stories from the New Testament, Life of Jesus in Pictures and The Boy Who Dreamed Dreams and Other Stories from the Old Testament. Shirley’s childhood toys also featured metal animals and figurines that added to the variety of miniature scenes she could recreate through play. These childhood belongings were a source of comfort to her and a reminder of a childhood that was all too soon replaced by the rigours of farm labour and household management.

Childhood museum collections of a religious nature may be important for a number of reasons. Geoff Troughton has noted that the high levels of involvement by children in faith communities, so often overlooked in historical literature in New Zealand, represent a high level of religious investment in children and ‘reinforce a correlation of religion with childhood’.4 Shirley’s personal faith story may be discerned within these simple objects. By introducing the concept of play, they complement other religious objects in Te Manawa’s collections like christening gowns and spiritual literature. In doing so they speak to us of another dimension of childhood engagement with religion – favourite objects imbued with memories which, in this case, stem from the reinforcement of a heroic narrative encountered through imagination and play.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Annette Nixon and members of the Brown family for additional information about Shirley Brown’s life.

Footnotes

- Wanganui Chronicle, 20 December 1930, p. 26. ↩︎

- Manawatu Times, 3 December 1940, p. 9. ↩︎

- Townsend, ‘Colonising Through Play’. pp. 58–62. ↩︎

- Troughton, ‘Religion, Churches and Childhood in New Zealand’, p. 39. ↩︎

Bibliography

Townsend, Lynette, ‘Colonizing Through Play: The Crowther’s Noah’s Ark’, in Annabel Cooper, Lachy Paterson and Angela Wanhalla, eds, The Lives of Colonial Objects, Otago University Press, Dunedin, 2015, pp. 58–62.

Troughton, Geoffrey, ‘Religion, Churches and Childhood in New Zealand, c. 1900–1940’, New Zealand Journal of History, vol. 40, no. 1, 2006, pp. 39–56.

Leave a comment