Simon Johnson

This brightly coloured toy truck was made during the 1950s or 1960s, the ‘Golden Age’ of Japanese tin toys.1 Two horses’ heads peer from the back of the truck, and as the truck trundles across the floor, these bob up and down courtesy of a crank attached to the back axle.

Lithographed tin toys were a product of 19th century industrialisation. They were made in large factories employing low paid labour on a ‘piece work’ basis in which workers were paid according to their output. This was a process common to much of the growing market for cheap consumer goods and remained unchanged until well into the 20th century.

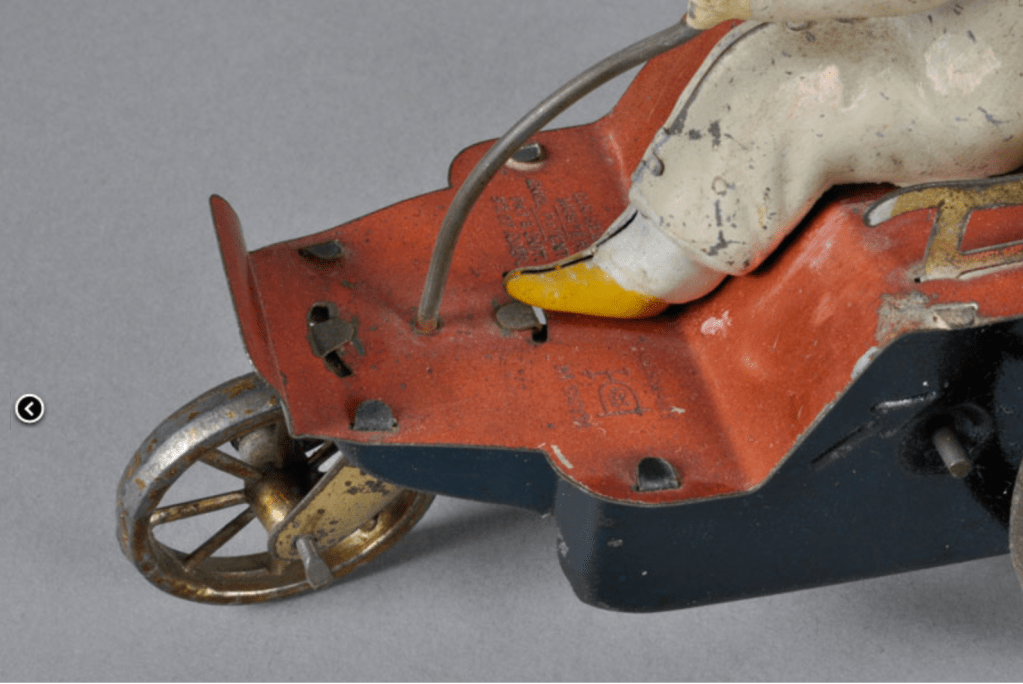

The first major tin toy producers were German. They ranged from the complex, highly finished boats, vehicles and railways made by Marklin and Bing, to the cheap and cheerful clockwork novelties made in their millions by Ernst Paul Lehmann’s factory in Brandenburg. The ‘Zikra’ toy zebra pulling a cart, featured here, is an excellent example of Lehmann’s output. Although made some sixty years later, the Japanese-made horse truck is similar both in its constructional technique and the market it was aimed at.

Tinplate toys are made from chromolithographed sheets of tinplated mild steel.2 These were then pressed into shape using moulds and assembled using a system of tabs which fitted into neighbouring slots.

After the First World War, German toy manufacturers were eclipsed by those of Great Britain and the United States. This was largely due to the rejection of German products after a war in which all things German had been demonised by British propaganda. Japan also entered the market, although as a less significant player. It too, was industrialising, and had announced its growing power by destroying the Russian navy in the Battle of Tsushima in 1905 and joining the Allies in the Great War. Japanese ships patrolled the Pacific, freeing the British Navy for the European sphere. New Zealand and Australia viewed this development with suspicion.

The golden age of Japanese tin toy making came in the decades following the Second World War. An important goal of the occupying Allied forces was to rebuild the Japanese economy. To do this the manufacture of consumer goods was promoted, with the United States providing a guaranteed market.3 By the mid–1950s Japan was world leader in tin toy production with well over one hundred toy making companies employing mainly female labour.

The toys themselves cover a spectrum with novelties at one end and large, highly detailed models of American cars and trucks at the other. Most of the novelties, such as animals playing musical instruments and skating clowns, were powered by clockwork. The vehicles, including Te Manawa’s horse truck, had a friction motor. This consisted of a heavy flywheel geared to the back axle. By pushing the vehicle forward several times the mass of the spinning flywheel would carry it forward for a few metres. By the 1960s many of the more expensive vehicles were battery powered with a separate control unit on an extension cord for the ‘driver’.

Te Manawa’s horse truck appears to have been made by a company called Masakiya. It does not represent a specific type of truck and is powered by a simple friction motor. It is a novelty, a Christmas stocking filler, and would have been relatively cheap to buy when new.

The name ‘Masakiya’ does not appear on the truck, only a logo resembling a mountain that was perhaps intended to mimic the more famous ‘Alps’ brand. However, identical horse floats appearing on the websites of specialist toy dealers identify them as Masakiya products.

Nothing appears to have been recorded about this company in books on tin toys in English or in online lists of Japanese toy companies.4 We do know that there were a large number of factories producing consumer goods in Japan after the Second World War and that many vanished as fashion and manufacturing processes changed. Only a few toy companies like Tomy and Bandai made it into the 21st century.

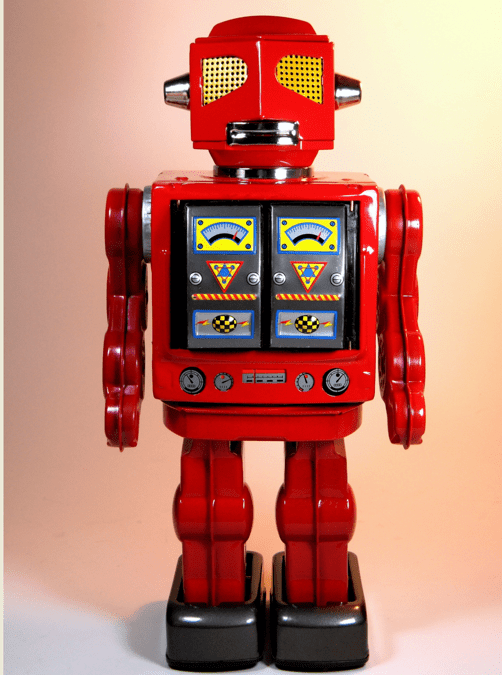

The Japanese tin toy industry was eclipsed in the 1960s by plastics. Improved injection moulding techniques enabled greater surface detail while offering the imagined safety of a softer material. This was a worldwide trend which Japan was quick to follow, and affected most areas of manufacturing. Sadly, the bright and funky appeal of chromolithographed tinplate toys was lost, including the friction drive buses with ‘passengers’ looking out of their windows, the American sedans with brightly coloured tin upholstery and, best known of all, metal robots with battery powered flashing eyes and tin printed dials on their chests.

Footnotes

- Tanner, ‘Toy Robots in America, 1955–75’, p. 125. ↩︎

- See Cieslik, The History of EP Lehmann, 1881–1981, for general information on tin toy making. ↩︎

- Tanner, ‘Tin Robots in America, 1955–75’, p. 125. ↩︎

- Elsass, ‘Japanese Tin Toys’; Dockerill, ‘Guide to Japanese Tin Toy Trade Marks’; Ralston, Tinplate Cars of the 1950s and 1960s from Japan. ↩︎

Bibliography

Brighton Toy and Model Museum, URL: https://www.brightontoymuseum.co.uk/in-the-museum/, accessed 30 October 2024.

Cieslik, Juren and Marianne, The History of EP Lehmann, 1881–1981, New Cavendish, 1982.

Dockerill, Kevin, ‘Guide to Japanese Tin Toy Trade Marks’, Dockerills, URL: https://dockerills.myshopify.com/blogs/news/guide-to-japanese-tin-toy-trade-marks, accessed 30 October 2024.

Elsass, Robert, ‘Japanese Tin Toys: A Craze that Rebuilt Post-war Japan’, Journal of Antiques and Collectibles, URL: https://journalofantiques.com/features/japanese-tin-toys-a-craze-that-rebuilt-post-war-japan/, accessed 30 October 2024.

Ralston, Andrew G., Tinplate toy cars of the 1950s and 1960s from Japan: The collector’s guide, Veloce Publishing, 2017.

Tanner, Ron, ‘Toy Robots in America, 1955–75: How Japan really won the war’, Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 28, no. 3, 1994, pp. 125–54.

Leave a comment