Simon Johnson

This perfect copy of a 1930s lounge suite with its slab sides and squared corners was made from tobacco tins in the 1930s or 1940s. The printed design showing through the paint helps to date the tins to this period. ‘Stewart’s Private Seal Special Fine Cut Tobacco’ and ‘Player’s Airman Virginia Cigarette Tobacco’ were popular brands.

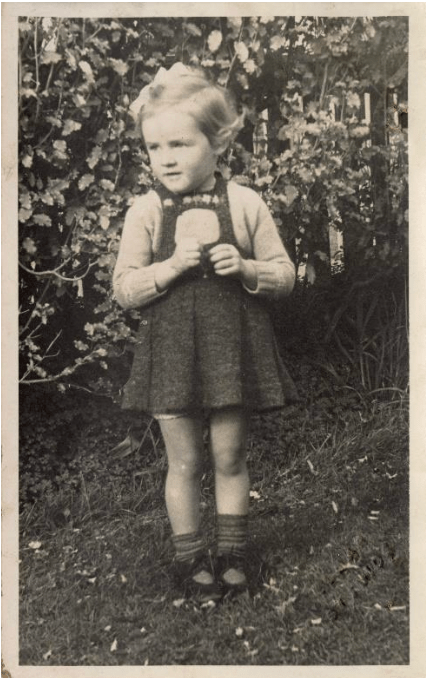

The donor, Dale Cooksley, who grew up in Manawatū, remembers playing with the suite as a child in the 1940s. She does not believe her father made the furniture. Cecil Edgar Cooksley married her mother, Olive Mary O’Donnell, in 1939. He served as a private in the Second NZ Expeditionary Force (2NZEF) in 1942, and subsequently became a Post Office worker.1

The lounge suite is made from 14 tobacco tins. The maker may have smoked the content of the tins or collected them from friends and relatives. Smoking cigarettes was not only associated with men by this time, but also with women. By 1920, annual per person consumption was 50 ounces (1.4 kilograms), and the effect of the war was to encourage further uptake.2 Tobacco tins typically contained an ounce of tobacco, which was sufficient for around 40–70 hand-rolled cigarettes. Each tin has rolled edges for safety, so the smoker did not cut themselves as they opened the tin to extract wisps of fine cut tobacco, making them suitable to hand on to children for their small collections of insects, buttons, and other objects.

p. 22.

The mid-twentieth century was a lean time for non-essential imports such as toys. Even when restrictions were eased under Sid Holland’s National government of 1949–57, English toys such as Meccano and Hornby railways were rarely available except around Christmas. Parents would preorder particular items to avoid missing out.

In this environment local entrepreneurs thrived. Backyard enterprises produced steam driven toys, model railway tracks, and Luvme brand soft toys, including dolls, teddy bears, animals and balls.3 Some, such as Fun Ho! cast aluminium vehicles, are still considered Kiwi icons.

Homemade toys were very much a part of this world. Large wooden trucks and locomotives could be made with a lathe and basic woodworker’s tools. Countless parents and grandparents made soft toys and dolls’ clothes. Dolls’ houses and furniture were very much a part of this tradition.

It is unlikely that the tobacco tin lounge suite was intended for a dolls’ house. At 257mm long the couch is too large, and would be better suited to dolls’ tea parties on the back lawn. It reflects a world in which pipe smoking and roll your own cigarettes were commonplace and empty tobacco tins were used in the home for storing small objects such as nails, screws and electrical fittings. My own garage work space contains a variety of such tins, inherited from my father.

As can be seen from this photograph of a typical interwar couch, the shape of the tobacco tins was ideal for a doll-sized model.

The tins making up the suite have been soldered together. Solder is an amalgam of tin and lead. The higher the proportion of tin, the harder the solder. Today, solder is mainly used by plumbers and electricians, but before the advent of ‘super glues’ it was commonly used in the home for metal repair. Before the 1960s most glues were made from animal products such as fish skin, and were of no use for metalwork.

Since many home appliances and toys were made from tin or mild steel, an ability to work with soft solder was seen as a useful and manly skill. Boys’ magazines such as the Meccano Magazine carried advertisements and articles on how to solder, and today’s collector of artefacts from tin toys to alarm clocks will often find items which have been repaired with solder.

Home soldering irons were nothing like the light, electrically powered models which are used for electrical work today. The business end or ‘bit’ was a block of copper narrowed to a tip which might be heated on a gas ring or a charcoal fire. It was carried on a steel shaft with a wooden handle at the end.

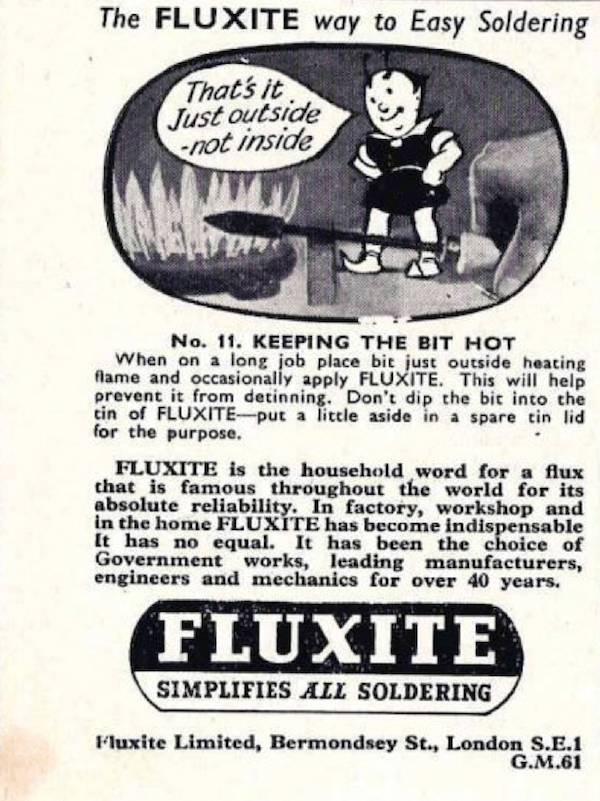

The Fluxite advertisement below shows the kind of soldering iron used to join the tins of Te Manawa’s dolls’ lounge suite being heated on a gas ring. Fluxite was a brand of flux, a compound used to cause liquid solder to run between the surfaces to be joined. Whoever made the tobacco tin lounge suite understood this process. All the solder has run into the joints between the tins, leaving none on the surface.

We’ll leave the last word to Dale, who was a longstanding volunteer at Te Manawa due to her expertise in conservation cleaning and packing methods:

I’ve always been interested in museums and the artifacts have always fascinated me. The Wellington and Whanganui museums were the only ones I knew as a child, and I remember seeing all the different things they had. I remember once I also went to the Waipu Museum, way up north of Auckland, which was jam-packed with artefacts and people’s memories, and the Auckland Museum.4

Footnotes

- Cecil Edgar Cooksley, Online Cenotaph, https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/war-memorial/online-cenotaph/record/130676?srt=relevance&n=cooksley&from=%2Fwar-memorial%2Fonline-cenotaph%2Fsearch&ordinal=3, accessed 26 November 2024. ↩︎

- Phillips, ‘Smoking – Cigarettes rule: 1900–1960’. ↩︎

- Veart, Hello Girls and Boys!, pp. 120–81. ↩︎

- McKergow, ‘Voluntary Work at Te Manawa’, p. 6. ↩︎

Bibliography

McKergow, Fiona, ‘Voluntary Work at Te Manawa: A Conversation with Dale Cooksley’, Te Manawa Museum Society Newsletter, no. 3, June 2009, pp. 6–9.

Phillips, Jock, ‘Smoking – Cigarettes rule: 1900–1960’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, URL: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/smoking/page-2, accessed 26 November 2024.

Veart, David, Hello Girls and Boys! A New Zealand Toy Story, Auckland University Press, 2014.

Leave a comment