Stuart Schwartz

In my own collection of items used by New Zealanders in their everyday lives in the past are dolls produced by New Zealand toy and doll-making companies. Of particular interest to me are dolls that represent peoples of Māori, Pacific and African heritage.

The Black doll illustrated here found its way into Te Manawa Museum’s collection by donation following the last owner’s death. It belonged to the donor’s mother, Ngaire Abbiss (née Summers), who was born in 1938, and was one of three treasured childhood items that Ngaire kept throughout her life, the others being a white composition doll and a plush teddy bear.

The doll was manufactured by the Reliable Toy Company Limited, established in Toronto, Canada, in 1920.1 Ngaire’s example shows signs of considerable use, including worn patches of hair and stubbed fingers and toes. The damage clearly reveals it is made of a sawdust mixture known as composition. Pristine examples of this doll in other collections reveal the original paint has largely worn off the hair, eyes and lips.2 It is unknown who made the red hood and white dress with blue flowers that the doll is wearing.

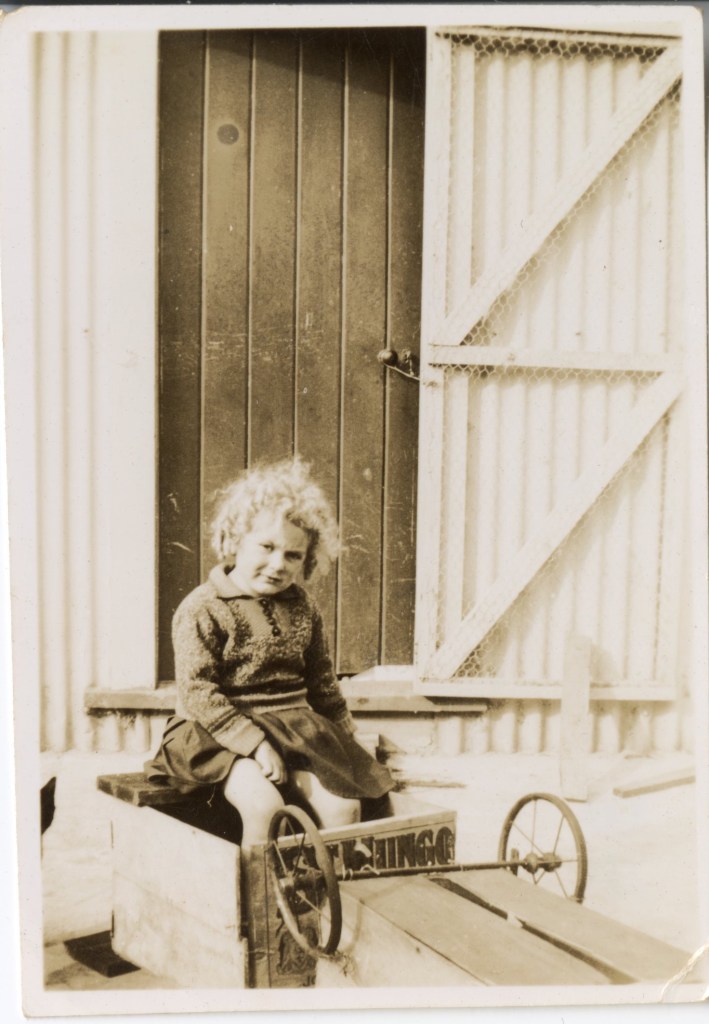

Ngaire was a well-photographed child, who grew up on the outskirts of Feilding. Her parents, Eleanor Read and Leonard William Summers, were dairy farmers. The following sequence of photographs gives a sense of an early childhood largely spent outdoors.

Is it unusual that a mid-century Black doll made in Canada found a home on a New Zealand farm? I would suggest from my collecting activities that the answer is probably not as complicated as it would seem.

My personal interest in Black dolls began with a fascination with dolls often termed ‘gollies’ or ‘gollys’, which I found when shopping for New Zealand heritage items at a wide range of op shops, charity shops and second-hand stores.

I never remember encountering similar dolls in the United States, my country of birth. If a Black doll was to be found there it more than likely would have been called a ‘pickaninny’, a derogatory term for young Black children often heard in the American South.

The profusion of historic gollies available throughout New Zealand from the 1990s to the present day speaks of the love for these dolls, whether factory-made or home-made. Aside from op shops, I also found new gollies on shelves in gift shops and at souvenir shops at the major New Zealand airports.

Te Manawa Museum has two golliwoggs in its collection, both home-made. One belonged to the late Cynthia Purchas (born Rawson), who was a child in the 1920s, and it was made of cotton fabric. The other is knitted in wool and part of the extensive Elliott doll collection donated to the museum by the late Julia Wallace, a former principal of Palmerston North Girls’ High School.

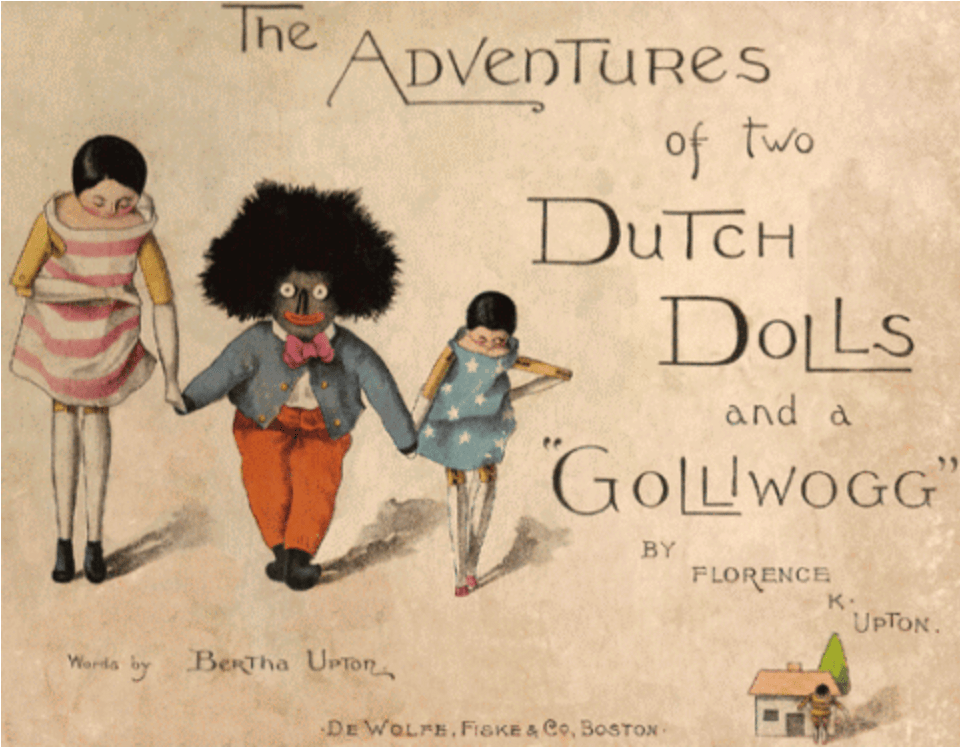

The origins of the golly, or golli as sometimes seen on store labels, can be traced to an American-born woman named Florence K. Upton. She was born in New York City to English parents in 1873. Her father died when she was 16. When she and her mother went to England to live, the young Florence took a Black doll with her that she named ‘Golliwogg’. The origin of the word ‘golliwogg’ is uncertain, but it is widely understood that the term signifies a cartoonish cloth doll that is a racist caricature of Black people.

Florence K. Upton’s famous book, The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and a Golliwogg, was published by Longmans, Green and Company of London and New York in 1895. It became a huge success which led Florence to produce a dozen more golliwogg books in the period up to 1909. Florence illustrated the books and her mother Bertha provided the text.3

New’s Zealand’s colonial newspapers were positive adults and children alike would enjoy Florence K. Upton’s new picture book:

Many delightful picture books are promised, and one is out. This is “The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and a Golliwog,” by Miss Upton. Grown-ups will enjoy looking through it, and to an imaginative child the Golliwog will be a thing of beauty and a joy for ever, or at least until the next picture book turns up.4

In the early 20th century, young boys were often favoured with the gift of a golliwogg when girls might be given the more feminine porcelain or composition dolls.5 This pattern continued through to the 1930s, when it was much more likely for a boy to choose to dress as a golliwogg for a fancy dress party than a girl.6

The sale of golliwogg dolls and books depicting gollies were banned in England in the 1960s as being offensive to Black people. Enid Blyton’s ‘Noddy’ children’s books were also banned because of the inclusion of a mischievous golliwogg in her stories.

In 1968, civil rights activists Lou Smith and Robert Hall formed a company called Shindana Toys – a Swahili word for competitor – to manufacture Black-oriented toys as a community development strategy and for an African American children’s market that had been ignored. It was intended that Black children would develop a positive self-image from playing with the company’s line of vinyl baby dolls, rag dolls, fashion dolls and celebrity action figures.7 Above all, the company’s aim was to manufacture authentically Black dolls, and not ‘white dolls “dipped in chocolate”’.8

This was a major break from the approach of the Reliable Toy Company Ltd in Canada, which manufactured identical composite dolls in a range of skin tones. It is this above all that makes Ngaire Abbiss’s Black doll a product of its time.

Footnotes

- Reliable Toy Co Ltd, ‘50th Anniversary’. ↩︎

- Doll, Reliable Toy Co Ltd, 1920–1974, D-8545, Canadian Museum of History. ↩︎

- ‘Florence Kate Upton’, Wikipedia. ↩︎

- Evening Star, 30 November 1895, p. 5 (supplement). ↩︎

- See for instance, Wanganui Chronicle, 20 December 1906, p. 7. ↩︎

- See for instance, Manawatu Times, 15 August 1931, p. 15. ↩︎

- Goldberg, ‘Black Power in Toyland’, pp. 120–62. ↩︎

- Goldberg, ‘Black Power in Toyland’, p. 133. ↩︎

Bibliography

Doll, Reliable Toy Co Ltd, 1920–1974, D-8545, Canadian Museum of History, URL: https://www.historymuseum.ca/collections/artifact/103932 (accessed 12 April 2025).

‘Florence Kate Upton’, Wikipedia, URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florence_Kate_Upton (accessed 12 April 2025).

Goldberg, Rob, ‘Black Power in Toyland’, in Rob Goldberg, Radical Play: Revolutionizing Children’s Toys in 1960s and 1970s America, Duke University Press, 2023, pp. 120–62.

Reliable Toy Co Ltd, ‘50th Anniversary. Fifty Years of Leadership in the Toy Industry. Dolls’, Canadian Museum of History, URL: https://www.museedelhistoire.ca/canadaplay/media/pdf/8208-561-RED-3952-IMG2009-0416-0031-Dp1.pdf (accessed 12 April 2025).

Leave a comment