Mike Roche

Brooches made from the beaks of dead birds were prized pieces of jewellery in the early 1900s. Some 125 years on, these items of women’s jewellery seem rather grotesque. This is especially so when the species in question, huia (Heteralocha acutirostris), was iconic for both Māori – especially Ngāti Huia ki Horowhenua – and settler society.

Huia are usually regarded as being extinct from 1907, although this date has been questioned and some populations may have survived beyond this time.1 They were largely limited to the forests of the Remutaka, Tararua and Ruahine ranges. Traditionally, high-ranking Māori – both men and women – adorned themselves with huia feathers and sometimes beaks and bird skins.

European settlers were struck by the difference in the length of the beaks between males and females, the latter being downward curving and considerably longer than the males; indeed, early European naturalists for a time thought they were two separate species. In 1892 huia were added to the list of protected species under the Animals Protection Act and given ‘absolute protection’ in 1903.2 These legislative measures proved ineffective.

At a time when forest clearance for land settlement was reducing their habitat, huia were also hunted by European settlers to obtain scientific specimens, for mounting and displaying in glass cabinets in private collections, as well as for their feathers and beaks as adornments. The female beaks were fashioned into women’s brooches with the addition of clasps and pin, as sometimes were the feet and leg bones.3 Some examples also survive of two shorter male beaks joined together to form a single brooch.

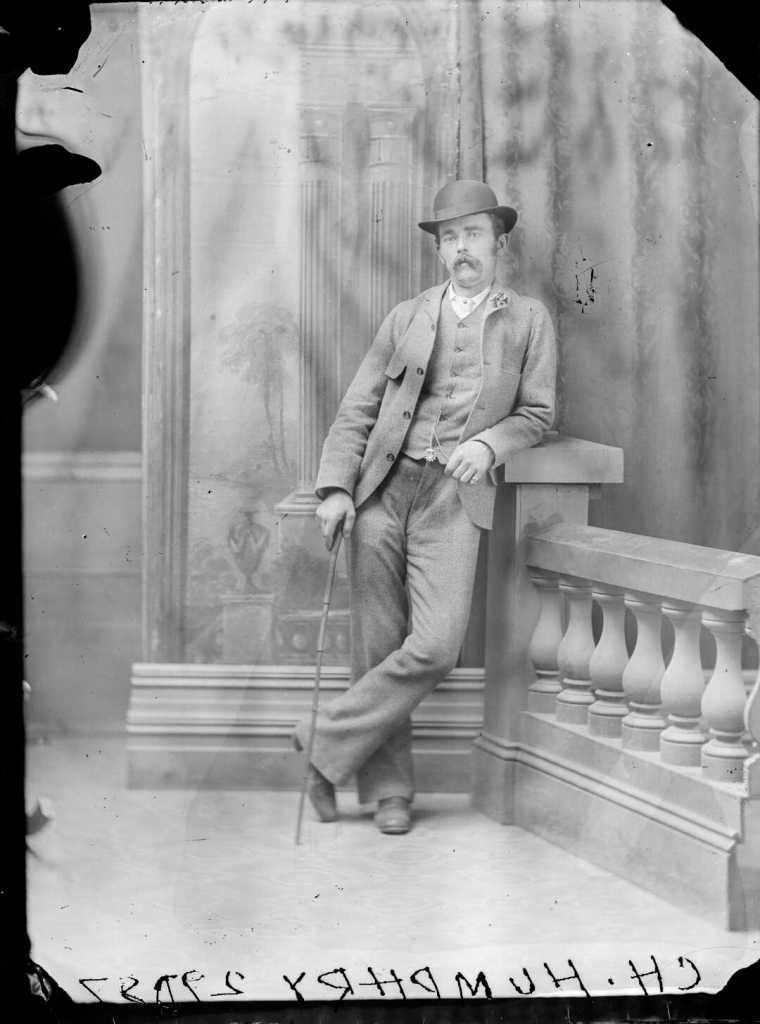

This particular brooch was crafted from a female huia beak shot by Charles Henry Humphrey (1862–1945) in the Ruahine ranges around 1904. Many huia were hunted by men working in road and rail construction camps in the ‘Taihape-Moawhango area’, as described by Dominion Museum ethnologist W.J. Phillipps. Some of the last Dominion Museum search parties seeking to catch live specimens also looked in this vicinity in 1909.4

Humphrey was born in England and accompanied his family to New Zealand as a 14-year-old in 1876. In the early 1880s and 1890s he was an orchardist in the Marton district. Humphrey was one of 40 volunteers from the Rangitikei Rifles, which drilled in Marton. He was also among the 1,600 troops, led by Native Minister James Bryce, that were involved in attacking Parihaka on 5 November 1881, arresting Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi and ruthlessly ending their campaign of passive resistance to land sales.5

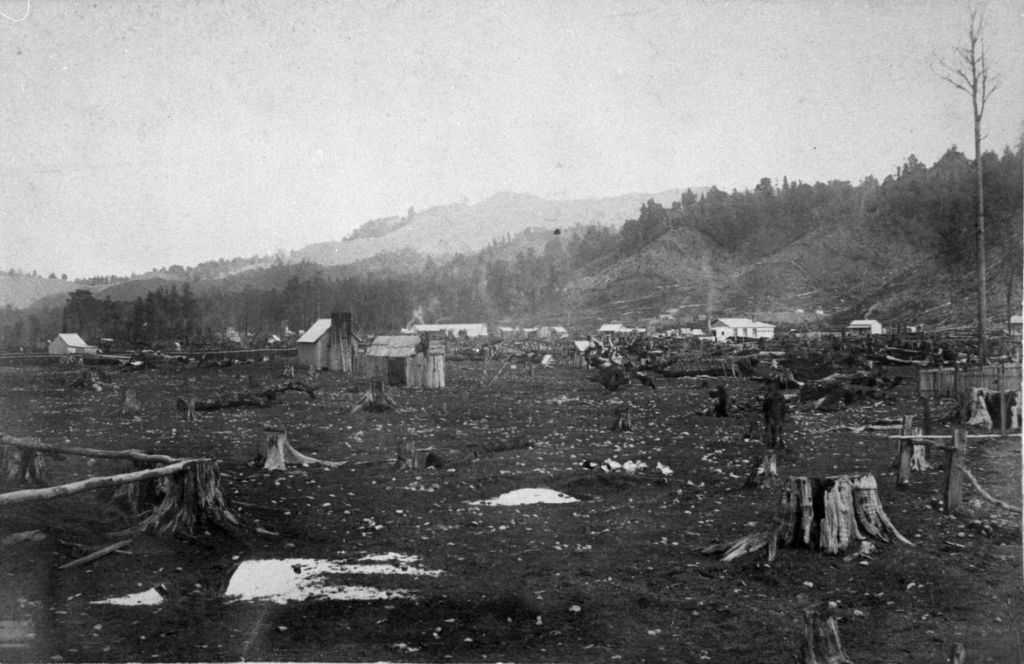

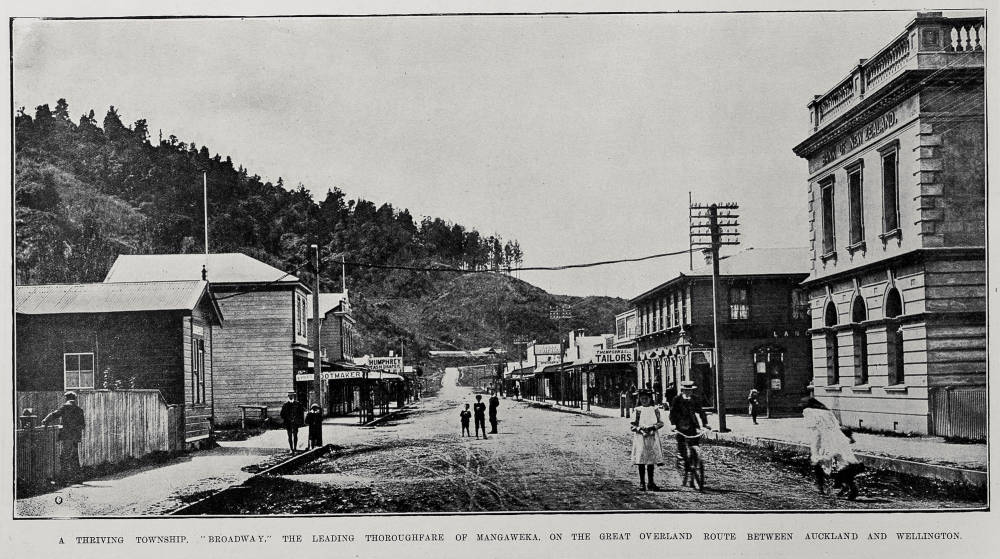

Humphrey married Agnes Douglas Armstrong (1864–1918) in Marton in 1883. In 1903 they moved to Mangaweka, where the first town sections had been sold in 1897, and where Charles took over a drapery and haberdashery business. In 1909, on the occasion of the wedding of one of his daughters, he was described in the local newspaper as the ‘well known and popular draper of this town’.6 By 1914 Humphrey was living with one of his sons on a farm near Taumaranui and he died in Hamilton in 1945.

Humphrey was an excellent marksman and won several shooting trophies. Family tradition has it that he shot five female huia in 1904, three years before their last ‘reliable sighting’.7 These he had made into brooches. Huia were not difficult to hunt, suggesting that he was not shooting them for sport but for their feathers and beaks. Individual feathers were sold for 10/- in 1901.8 By 1904 there were only occasional prosecutions for killing or selling them, typically resulting in a £10 fine.

There were few acclimatisation society officers for Humphrey to be worried about. The Waimarino Acclimatisation Society in 1904 had a single ranger, Walter Merson (1862–1944), an Ohakune farmer, operating from Raetahi, and the Society was mostly interested in introducing hares and trout.9 Living in remote Mangaweka and shooting in the Ruahine ranges, Humphrey would have been unlucky to have been prosecuted. It would seem unlikely in any case that he would have sighted the prohibition notices protecting huia that were published in the New Zealand Gazette in March 1903.10

Noted ornithologist Sir Walter Buller claimed with Darwinian overtones in 1897:

It is one of the doomed species … although the huia loves the mountain tops, it is driven down by the cold in winter to the lower forests. These are quickly disappearing before the woodman’s axe in the rapid progress of settlement. The home of the bird is invaded, and the struggle for existence is becoming every day more severe.11

The only slender hope he believed lay in moving specimens to offshore island reserves.

It is difficult to know what motivated Humphrey to shoot birds of a species that was recognised as being close to extinction in 1904. He may, like Buller, have believed nothing could save the huia while simultaneously acting to acquire a scarce and hence valuable ‘trophy’.

Huia brooches were fashionable items appearing towards the end of the ‘mid-Victorian period of jewellery’ which replaced the heavier grandiose brooches of the 1860s. Grouse foot brooches from Scotland provide an example of a similar style of jewellery. Historian Andrew Wood provides clues as to how to understand huia brooches:

Such jewellery expresses the complex Victorian relationship with nature and their dominion over it. This becomes particularly significant, even aggressive in the colonial setting, as emblematic of dominion over land, native species, and even indigenous peoples … .12

Wood also concedes that the huia was a symbol of a ‘kind of nascent nationalism, an announcement of belonging to place’. He provides two additional ways of thinking about Humphrey’s actions. First, that it was an extension of ideas about people’s dominion over nature – ideas that have their biblical source in the book of Genesis. And second, the wearing of huia brooches was a means of marking out New Zealanders as occupying a distinctive place within the British empire.

The use of huia feathers as fashionable adornments in Pākehā men’s hat bands is considered to have been accelerated by the Duke of York’s visit to New Zealand in 1901.13 Although as Buller’s remarks indicate, huia were facing extinction well before this time. Some huia beak brooches in museum collections elsewhere also date from the turn of the 20th century.

Today it is impossible to know why Humphrey shot the five huia other than to obtain beaks, but it is interesting to consider how his actions can be placed against a bigger colonial backdrop and fashions in jewellery over and above being simply a gift for his wife Agnes in her fortieth year.

The brooch remained in the Humphrey family until it was donated to Te Manawa in 2021 to ensure that it is cared for in perpetuity. The other four huia may have been given as presents or sold. With twelve tail feathers per huia, sellable at about 10/- each, Humphrey would have recouped £30 to offset jeweller’s expenses.

Finished with a gold mount on a female huia beak of approximately 10 cm length, there is no obvious manufacturer’s mark. The mount is decorated with what may be a stylised, koru-like fern frond surrounded by leaves and other vegetation, providing an example of the ‘nascent nationalism’ and identity with place identified by Wood.

Some huia brooches have been attributed to Whanganui jeweller Samuel Drew (1844–1901), and the firm was continued by his son Henry who was a skilled taxidermist.14 Existing Drew brooches all have the firm’s mark on them, which is lacking in the Humphrey example suggesting it is not their work. In addition, the craftsmanship of the Humphrey brooch is a step below some of the more elaborate Drew examples.

Humphrey may have had the brooch made locally in Mangaweka where one of his neighbours George Henry Carter was a watchmaker and jeweller. In 1909, Carter was advertising that he was manufacturing a range of rings and keepers as well as pig ‘Tusks Mounted in Gold From 15s Upwards’ and gold and silver medals, which suggests huia beak brooches would have been well within his capabilities.15

Fashions and sensibilities change. Today huia beak brooches and other types of jewellery and accessories made from dead birds evoke feelings that are far different from those of the hunters who shot the remaining huia and the jewellers who created such brooches.

Footnotes

- Galbreath, R., ‘The 1907 ‘last generally accepted record’ of Huia’, pp. 239–242. ↩︎

- Onslow, ‘Native New Zealand Birds’, pp. 1–4; Inward correspondence, R24741613, Archives New Zealand; Inward correspondence, R24855658, Archives New Zealand. ↩︎

- Personal communication with Pamela Lovis, Alexander Turnbull Library, 2025. ↩︎

- Phillipps, The Book of the Huia. ↩︎

- ‘Charles Henry Humphrey, 8 May 1862–2 July 1945’, FamilySearch; ‘Rangitikei Rifles to the Front’, Wanganui Herald, 29 October 1881, p. 2. ↩︎

- ‘Mangaweka’, Rangitikei Advocate and Manawatu Argus, 26 April 1909, p. 5. ↩︎

- Te Manawa Museums Trust Collections Committee Acquisition Report for August 2021. ↩︎

- [Untitled], Mataura Ensign, 30 April 1901, p. 2. ↩︎

- Inward correspondence, R24848682, Archives New Zealand. ↩︎

- New Zealand Gazette, pp. 794–798. ↩︎

- Buller, ‘The vanishing forms of bird-life of New Zealand’, p. 5. ↩︎

- Wood, ‘New Zealand Huia Bird Brooches’, p. 4. ↩︎

- ‘Newspaper Notions’, Free Lance, 20 April 1901, p. 6; Renault, Dressed, pp. 267–273. ↩︎

- Noble, ‘Drew, Samuel Henry’. ↩︎

- ‘Mangaweka Advertisments’, Rangitikei Advocate and Manawatu Argus, 28 January 1909, p. 8. ↩︎

Bibliography

Buller, Sir Walter, ‘The vanishing forms of bird-life of New Zealand’, Press, 11 January 1897, p. 5.

‘Charles Henry Humphrey, 8 May 1862–2 July 1945’, FamilySearch, URL: https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/KNH1-XQT/charles-henry-humphrey-1862-1945 (accessed 20 June 2025).

Galbreath, R., ‘The 1907 ‘last generally accepted record’ of Huia (Heteralocha acutirostris) is Unreliable’, Notornis, vol. 64, no 4, 2017, pp. 239–242.

Inward correspondence: Governor, Wellington. Date: 27 February 1892. Subject: Declaring the Huia to be within the operation of the Animals Protection Acts, R24741613, Archives New Zealand.

Inward correspondence: Governor, Wellington. Date: 5 March 1903. Subject: Protecting Huia absolutely, R24855658, Archives New Zealand.

Inward correspondence: Governor, Wellington. Date: 18 October 1905. Subject: Appointing Rangers under Animals Protection Acts, District of Waimarino, R24848682, Archives New Zealand.

New Zealand Gazette, no. 20, 19 March 1903, pp. 794–798.

Noble, Kaye, ‘Drew, Samuel Henry’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1993. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/2d18/drew-samuel-henry (accessed 20 June 2025).

Onslow, W.H., ‘Native New Zealand Birds’, Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives, 1892, H-6, pp. 1–4.

Phillipps, W.J., The Book of the Huia, Whitcombe and Tombs, Christchurch, 1963.

Regnault, Claire, Dressed: Fashionable Dress in Aotearoa New Zealand 1840 to 1910, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2021.

Wood, Andrew, ‘New Zealand Huia Bird Brooches’, Jewellery History Today, no. 48, Autumn 2023, pp. 3–5.

Classroom Resources

Please refer to Mantle of the Expert.

Leave a comment