Mike Roche

In 2023 a pair of stuffed huia (Heteralocha acutirostris) in a glass case along with hummingbirds, rocks and foliage were sold at auction in the UK for a record £220,000 – about $NZ470,000 – well above the expected price of £15,000 to £25,000.1

Endemic to New Zealand, huia were, and continue to be, revered by Māori. High-ranking men and women wore huia feathers and sometimes beaks and bird skins as adornment. From the 1880s, European settlers shot huia for their tail feathers, made ornaments out of beaks, and hunted specimens for scientific and private collections. Huia were restricted to areas in the Remutaka, Tararua and Ruahine ranges, and land settlement further reduced their habitat.

In 1890, the governor Lord Onslow’s second son, the first vice-regal child born in New Zealand, was christened ‘Huia’, a name gifted by Ngāti Huia of Ōtaki after an ancestral figure.2 Simultaneously, Ngāti Huia urged the governor to give full protection to the birds. Onslow obliged and was instrumental in having huia added to the list of protected species under the Animals Protection Act in 1892.3 Local ornithologist Sir Walter Buller (1838–1906), however, described them as a ‘doomed species’ in 1897.4 The Animals Protection Act was flawed in that species needed to be specifically exempted from hunting by district acclimatisation societies and it was not until 1903 that the next governor, Lord Ranfurly, ‘prohibited absolutely the taking or killing of the Huia’.5

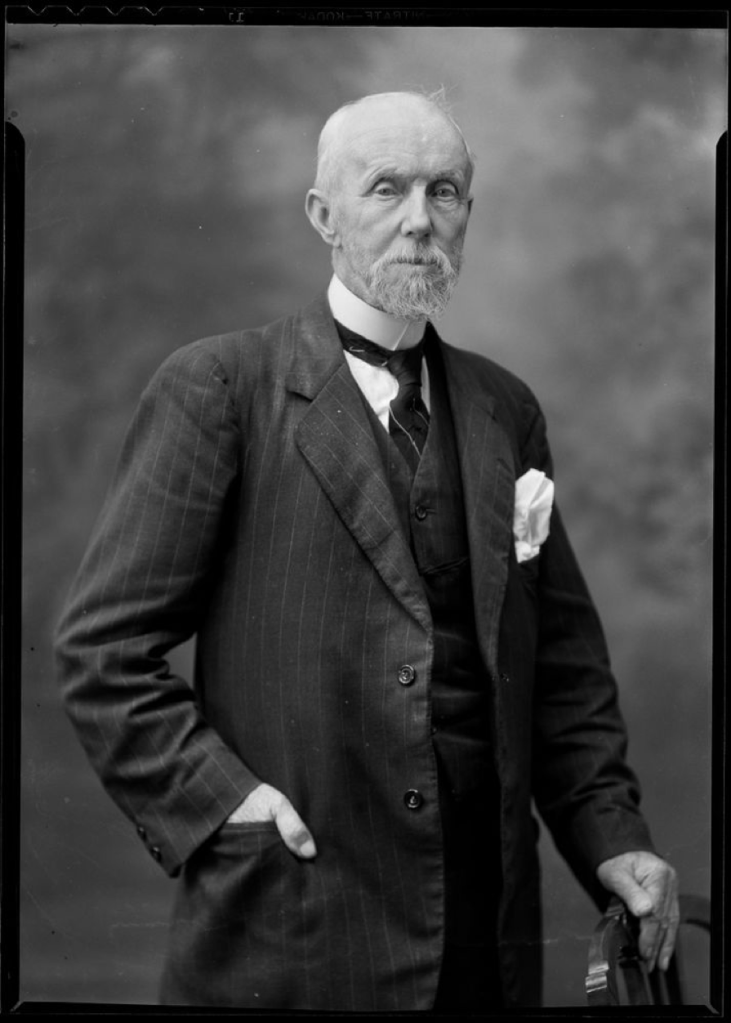

The usual date for the final sighting of a pair is 1907 near Mt Holdsworth in Wairarapa and is attributed to W.W. Smith (1852–1942), an accomplished field naturalist.6 In a letter to the New Zealand Times, he summarised his efforts to preserve huia dating back to 1904, including his offer to snare live huia so they could be moved to island bird sanctuaries. Smith had a fleeting connection with Palmerston North as curator of the Esplanade. But in 1908 he left Palmerston North abruptly, having been derided by the mayor as a ‘common cabbage gardener’.7

Some doubt has recently been cast on the 1907 date by historian of science Ross Galbreath, while W.J. Phillipps, a former registrar and ethnologist at the Dominion Museum, the precursor to Te Papa, had earlier documented other plausible later sightings in The Book of the Huia.8

The provenance of Te Manawa Museum’s pair of male and female huia extends back only to 1945 when Rongotea farmer Edgar Dear (1901–1969) purchased the huia cabinet at a clearing sale, possibly in the Masterton area. The cabinet was on display in the hall of the Dear family home.9 A mallard duck, warbler nest, longtailed cuckoo (Eudynamys taitensis) or kohoperoa, and a kiwi skin (since removed by museum staff), all of unknown provenance, were later added by the family.

The cabinet was donated to Te Manawa by his widow Joyce (1909–1978) in 1974. It was displayed in the hallway of Tōtaranui from 1975 to 1994, mimicking its place in the Dear home. By 2023 the huia had deteriorated to the extent that they required the attention of a professional taxidermist, who noted that the difference in leg colouring from other specimens may be a product of the original preservation techniques.10

Masterton was close to the last known habitat of the huia. That the cabinet was purchased at a ‘clearing sale’ points to a deceased estate sale which, when linked with the ‘last sighting’, suggests that the specimens were collected possibly as early as the 1880s or as late as the 1900s. Even in 1907 Smith claimed that ‘an unscrupulous and unfeeling wretch’ in Featherston was hunting huia for £1 each for a dealer in Wellington.11

The owners of the cabinet may or may not have shot the birds. The hunter probably relied on the skill of a professional taxidermist, though this was not necessarily the case. Some taxidermists shot, collected and stuffed birds to be onsold to private collectors, although by 1909 official permits were being declined for this purpose unless the specimens were for public or scientific purposes.12

Taxidermy has a long history but developed significantly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in part to better preserve scientific collections in newly-established public museums, including birds, which were suffering from insect damage which reduced their value as reference specimens. Some taxidermists mounted specimens on wire frames, while others used moulds.13 In Te Manawa’s instance we have the taxidermist’s recollection, from undertaking restorative work on a wing and tail, that the body – ‘the form’ – felt hard, suggesting use of the ‘wrapped wool wood method’ where the ‘form was made by carving balsa or some similar wood available at the time’.14

Furthermore, huia had 12 tail feathers which in the early twentieth century could sell for 10/- each.15 Writing in 1963, Phillips observed that of the 18 huia then in Auckland Museum’s collection three had 11 tail feathers and another seven, nine or 10, and of the 53 huia then in the Dominion Museum’s collection only six had the full 12 tail feathers, with 18 possessing from nine to 11.16 Te Manawa’s specimens each have a mere three feathers suggesting the sale of the rest at some point.

From the 1870s professional taxidermists were employed at Otago Museum, Canterbury Museum and the Dominion Museum, with Auckland Museum the main exception.17 Private taxidermists also advertised their services from the late nineteenth century. In many instances they met hunters and fishers needs by preserving deer heads and fish. The taxidermy skill of Napier’s Alexander Yuill was acknowledged in 1890. Masterton taxidermist John Jacobs advertised ins 1896. Somewhat later, in 1905, his wife Alice S. Jacobs, ‘Taxidermist and furrier’ of Wellington, was advertising her services in Wairarapa newspapers, albeit primarily for mounting deer heads.18 Private practical tuition was offered by Auckland taxidermist Philip G. Griffin in 1892.19 Various instructional books were advertised from the 1890s such as W. Hornaday’s Taxidermy and Zoological Collecting at 11/6d and Montagu Browne’s Practical Taxidermy for 9/-.20

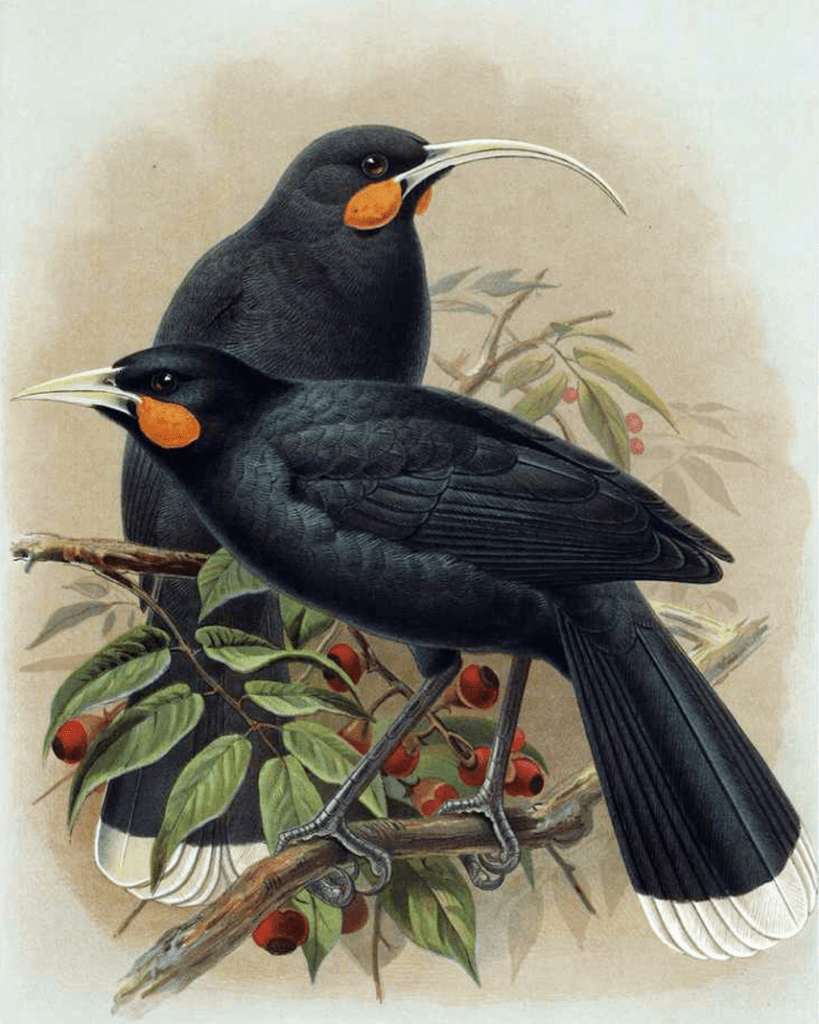

That Te Manawa’s cabinet contains a male and female huia may indicate that the birds were killed at the same time as early ornithological observations indicated huia paired for life. Even if this is not the case, the dimorphism most evident in the different length and shape of the beaks between male (short and blunt) and female (longer and curving) was a point of interest for ornithologists and more casual observers. Females with their long curving beaks seem to have attracted more interest.

We have only second-hand accounts of the birds in the wild, so it is difficult to be certain the specimens are authentically posed and with other extinct species this seems not to have always been the case. Some early displays of moa skeletons were for example assembled in such a way as to exaggerate their height. It is noticeable that the birds face to the front of the cabinet so that their beaks do not stand out as clearly as in the side profile.

This view was adopted in Johannes Keulemans’ engraving of huia for Buller’s A History of the Birds of New Zealand which enjoyed wide circulation. In another huia case at Te Manawa the two birds are posed sideways.21 Possibly this points to the Dear huia cabinet being an amateur assemblage and not commercially constructed in its entirety even if the birds were the work of a professional taxidermist.

PUBL-0012-02.

The Dear family’s glass cabinet and contents is a latter day version of the ‘cabinet of curiosities’ traceable to the sixteenth century where the social elite gathered natural history specimens and geological, archeological and historical items to impress and awe viewers. The cabinet and its contents were not intended as a museum tableau consistent with principles of ecological science. Instead the huia are perching on a branch of the exotic silver birch tree trimmed to fit the cabinet. The floor of the cabinet is covered with spagnum moss. Exotic and indigenous species are included.

The cabinet itself was not necessarily intended to house the two huia. It stands about 165 cm high, 72 cm wide and 39 cm deep (none of which convert neatly to inches suggesting the cabinet was not professionally constructed). The door handle is similar to those on dressing tables and cabinets dating from the 1910s.22 It features reproduction ‘Jacobean barley twist’ legs which typically date from the 1920s and were often produced in black stained oak.23 Whether the cabinet is stained oak or another species awaits expert examination. The plywood back is a light yellowy-orange colour which shows off the birds to greater effect than if they were against a dark background. New Zealand-made plywood manufactured from kahikatea, rimu, mataī and tanekaha became widely available after 1911. USA Oregon plywood was imported in the 1920s which matches with the date of the legs.24 However the plywood back of the cabinet could equally be made of American white oak. That the plywood back is a different wood and colour to the rest of the cabinet may also indicate a replacement panel.

The wood and style of construction suggests the cabinet dates from the 1920s and yet the huia were shot some time before 1907. This raises a question as to whether the birds were always in this particular display arrangement. There are other unanswered questions about modifications to the existing cabinet including whether the large single glass pane front is original. Observation takes us only so far and expert timber identification is required to reveal more about the cabinet.

Many mysteries surround the Dear family’s huia cabinet and its contents, but what is known or observable raises a host of intriguing questions about its provenance.

Footnotes

- ‘Sky-high price for stuffed NZ birds’, New Zealand Herald, 11 September 2023. ↩︎

- Onslow, ‘Native New Zealand Birds’, pp. 1–4. See Cox, ‘The Baptism of Huia Onslow’ for further information. ↩︎

- Onslow, ‘Native New Zealand Birds’, pp. 1–4; Inward correspondence, R24741613, Archives New Zealand. ↩︎

- Buller, ‘The vanishing forms of bird-life of New Zealand’, Press, 11 January 1897, p. 5. ↩︎

- Inward correspondence, R24855658, Archives New Zealand. ↩︎

- ‘The Huia’, New Zealand Times, 27 December 1907, p. 7. ↩︎

- ‘That Common Cabbage Gardener’, Manawatu Times, 11 March 1908, p. 5. ↩︎

- Galbreath, ‘The 1907 ‘last generally accepted record’ of Huia’, pp. 239–242; Phillipps, The Book of the Huia. ↩︎

- Edgar Dear huia cabinet collection record, 74/164/2, Te Manawa Museums Trust. ↩︎

- Personal communication with Antoinette Ratcliffe, The Sick Bay Taxidermy, 2025. ↩︎

- ‘The Huia’, New Zealand Times, 27 December 1907, p. 7. ↩︎

- Inward correspondence, R24766799, Archives New Zealand. ↩︎

- Faber, ‘The Development of Taxidermy and the History of Ornithology’, pp. 550–566. ↩︎

- Taxidermist Antoinette Radcliffe thought the posing was professionally done. Personal communication, 2025. ↩︎

- [Untitled], Mataura Ensign, 30 April 1901, p. 2. ↩︎

- Phillipps, The Book of the Huia, pp. 32, 35. ↩︎

- Crane and Gill, ‘William Smyth’, pp. 292–308. ↩︎

- Wises Directory, 1897; ‘Special Advertisements’, Wairarapa Daily Times, 22 March 1905, p. 1. ↩︎

- ‘Educational’, Auckland Star, 3 September 1892, p. 1. ↩︎

- ‘Booksellers and Stationers’, New Zealand Herald, 2 April 1892, p. 7; ‘Notes and Queries’, Otago Witness, 22 August 1895, p. 27. ↩︎

- For instance, a pair acquired from the then Massey University Ecology Department, 98/217/1, Te Manawa. ↩︎

- Cottrell, Furniture of the New Zealand Colonial Era, p. 442. ↩︎

- Lloyd Jenkins, At Home, p. 53. ↩︎

- Roche, ‘A Message on New Zealand Wood’, pp. 7–9. ↩︎

Bibliography

Buller, Sir Walter, ‘The vanishing forms of bird-life of New Zealand’, Press, 11 January 1897, p. 5.

Cottrell, William, Furniture of the New Zealand Colonial Era: An Illustrated History, 1830–1900, Reed, Auckland, 2006.

Cox, Elizabeth, ‘The Baptism of Huia Onslow’, Old St Paul’s Wellington, 24 March 2015, URL: https://osphistory.org/2015/03/24/the-baptism-of-huia-onslow/ (accessed 4 September 2024).

Crane, R. and B.J. Gill, ‘William Smyth (1838–1913), A Commercial Taxidermist of Dunedin, New Zealand’, Archives of Natural History, vol. 45, no. 2, 2018, pp. 292–308.

Faber, P.L., ‘The Development of Taxidermy and the History of Ornithology’, ISIS, vol. 68, no. 4, 1977, pp. 550–566.

Galbreath, Ross, ‘The 1907 ‘last generally accepted record’ of Huia (Heteralocha acutirostris) is Unreliable’, Notornis, vol. 64, no. 4, 2017, pp. 239–242.

Gill, B.J. ‘Size and Scope of the Bird Collections of New Zealand Museums’, Notornis, vol. 48, no. 2, 2001, pp. 108–110.

Inward correspondence: Governor, Wellington. Date: 27 February 1892. Subject: Declaring the Huia to be within the operation of the Animals Protection Acts, R24741613, Archives New Zealand.

Inward correspondence: Governor, Wellington. Date: 5 March 1903. Subject: Protecting Huia absolutely, R24855658, Archives New Zealand.

Inward correspondence: Letter from F.S.B. Walker, Secretary of Waimate Acclimatisation Society, to the Minister of Internal Affairs, 10 May 1909, R24766799, Archives New Zealand.

Lloyd Jenkins, D., At Home: A Century of New Zealand Design, Godwit, Auckland, 2004.

Onslow, W.H., ‘Native New Zealand Birds’, Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives, 1892, H-6, pp. 1–4.

Phillipps, W.J., The Book of the Huia, Whitcombe and Tombs, Christchurch, 1963.

Roche, M., ‘A Message on New Zealand Wood’, Australian Forest History Newsletter, no. 93, 2024, pp. 7–9.

Classroom Resources

‘Huia, the Bird of the Century’, Science Learning Hub Pokapū Akoranga Pūtaiao.

Leave a comment