Huhana Smith

This rare remu marereko (fan of tail feathers) of the extinct huia (Heteralocha acutirostris) was on safe deposit at Te Manawa by arrangement with its guardian for over a decade; it has been returned to private ownership.

Remu marereko signify rangatiratanga (chiefliness) and mana. Mana is a subtle influence of supernatural origin that exists throughout the universe. In an individual, mana promotes integrity, dignity and self-respect. Mana profoundly influences ways of being, but it is not something an individual can claim for themselves. Mana accumulates through a leader’s capacities and achievements, which are for others to acknowledge. Mana is expressed in an authority and leadership that in turn empowers others. Full tail feather fans worn in the hair at the back of the head indicate tapu, sacredness, status and recognised leadership qualities.

In 1997, curators Shirley Marie Whata and Pamela Lovis were preparing the exhibition Huia – Sacred Bird, Lost Treasure at The Science Centre & Manawatu Museum. At this time their colleague Marcus Boroughs visited his friend John Gilbertson at Oteka, a farm in the Ōmakere region between Waipukurau and Pourerere, and by chance noticed the framed remu hanging in a back bedroom. John was looking after the remu for his older sister, Gael Black, to whom he had given it after having it in his possession for some years.

With Gael’s permission, the remu was borrowed and conserved for display in the exhibition. It was photographed and documented, surface cleaned in a controlled vacuum, and had its backing board replaced with archival-quality materials. It was then reframed in the same manner as it was when found. The tail feathers were again anchored by a copy image of the notable warrior chief, Pātara Te Ngūngūkai.1 Fragments of feathers, the backing board and the original cropped image were placed in the archival box that safeguarded this taonga.

Huia – Sacred Bird, Lost Treasure, which opened in 1998, was dedicated to the memory of former director Mina McKenzie (Ngāti Hauiti, Rangitāne, Ngāti Raukawa and Te Āti Haunui a Pāpārangi), who had an extraordinary influence on the institution. The exhibition also acknowledged and enlivened the museum’s huia logo, rendered by renowned Ngāti Raukawa ki Kapiti and Ngāti Wehiwehi artist John Bevan Ford (1930–2005). The huia had inspired his work for the museum because the species had lived in the nearby Ruahine and Tararua Ranges. Huia are still of cultural significance to the iwi and hapū of the region. They lived only in the North Island, and in European times were confined to the ranges of the lower North Island. It is presumed that huia became extinct in the early twentieth century.2

Huia were highly prized – too much so for their own good. For Māori, huia feathers were a mark of high status. The name became associated with treasured things: waka huia were containers for precious items. Europeans were also captivated by the huia’s beauty and unusual features. In the late nineteenth century, Māori and Pākehā hunters slaughtered great numbers with shotguns and sold the skins to collectors and merchants. On scientific advice, the government attempted to organise the collection of birds for shipping to offshore islands where it was hoped they might survive undisturbed. This plan failed because dead specimens were worth more than live birds. There were unconfirmed sightings of huia in the wild for several decades after the last definite sighting in 1907.3

During my time as Senior Curator Māori at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2003–2009), I worked with a dedicated team of curators and collection managers (kaitiaki Māori) to reconnect taonga tuku iho (ancestral treasures) with their living descendants.4 Our team was conscious that many taonga in our care languished in silence, because – for many reasons – key connecting stories and details had not been passed on to successive kaitiaki (guardians).

When working on an environmental research project based in Horowhenua, I continued to wonder how significant treasures such as this remu left their original kaitiaki. Was it gifted or exchanged for unknown items? Two specialists at Te Papa at that time, Hokimate Harwood, Bicultural Science Researcher and Pamela Lovis, Senior Interpreter for Exhibitions, agreed that the remu was a significant treasure. The healthy obsession with huia that Pamela developed while curating the exhibition about them can be seen in the considerable research files now held at Te Manawa. She confirms that few (if any) complete huia tail feather arrangements for wearing that have all twelve feathers and down are held in public museums in Aotearoa New Zealand.5

Hokimate has developed a way to identify the bird species used in cloaks. She compares tiny samples of down feathers to the museum’s bird skins using microscopic analysis. While working at Te Papa, I was in awe of Hokimate’s ability to identify feathers, particularly huia feathers. It was a profound moment when we learnt that some black and difficult-to-see feathers laid out in a zigzag pattern amongst the very dark brown kiwi feathers of a kākahu (cloak) were actually huia feathers.

One reason why it is important to authenticate feathers is that purported huia feathers sometimes appear in online auctions with erroneous claims that they have been assessed by Te Papa specialists. Only microscopic assessment can categorically verify feathers. Some single feathers said to be from huia have turned out to be from Indian myna (Acridotheres tristis), duping auction house and purchaser alike.6

What of Pātara Te Ngūngūkai, whose image anchors this remu? His portrait first appeared on postcards in about the 1870s. An esteemed Tuhourangi warrior (toa), he fought against Waikato leaders such as Te Waharoa. The Scottish photographer James Valentine (1815–80) probably took the original photograph. This well-known photographer founded a business in Dundee in 1851 that later thrived as an internationally famous producer of picture postcards, especially from regions with fashionable resorts, such as Norway, Jamaica, Morocco, Madeira and New Zealand.7

Pātara Te Ngūngūkai was born around 1807. As a very elderly man he was to meet the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall at Rotorua during their 1901 tour, but died before he could do so. His tangihanga was downplayed so as not to sadden the royals or cast a pall over their visit.8 Several newspapers reported the ‘Death of an Old-Time Cannibal’ at Maketū, Bay of Plenty.9 While describing him as ‘a man of no rank’, they also acknowledged that he was ‘a great warrior in his young days’, especially during the 1834–6 wars with Waikato. He was also a tohunga charged with preparing ancestral remains for sacred rituals and their final interment in burial caves or vessels.

Notwithstanding his considerable mana and social standing amongst his people, it is very unlikely that Pātara Te Ngūngūkai was associated with this remu marereko. In the original framed arrangement, his image is definitely cropped from a Valentine postcard. We can safely assume that the popularised postcard image was used to represent huia feathers as a symbol of status, as in this colonial representation of an elderly Māori posed for the camera wearing a korowai, holding a taiaha and with huia feathers in his hair.

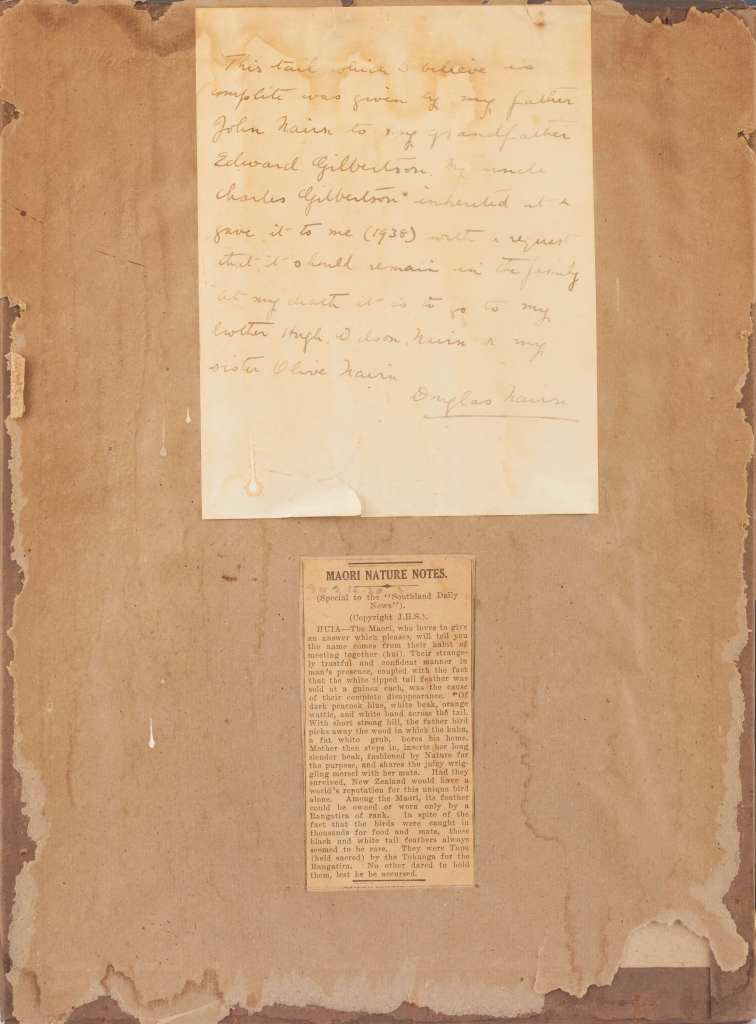

On the back of the original framed image, a note signed ‘Douglas Nairn’ adheres to the backing board above a small newspaper clipping, entitled ‘Maori Nature Notes’. The article, marked ‘special to the Southland Daily News’, suggests that Māori named huia for the birds’ habit of meeting (hui) and their trustful manner in human company. It observes that the valuation of feathers at a guinea each (approximately $200 today) would have contributed to the bird’s decline, and states that huia feathers were tapu (sacred) and worn only by rangatira.10

The handwritten note on the backing board reads:

This tail, which I believe is complete was given by my father John Nairn to my grandfather Edward Gilbertson. My uncle Charles Gilbertson inherited it and gave it to me (1938) with a request that it should remain in the family. At my death it is to go to my brother Hugh Wilson Nairn or my sister Olive Nairn.

Douglas Nairn

Gael Black and her brother, Tim Gilbertson, held their elderly relation Douglas Nairn in high regard. Tim remembered as a young teenager being dropped off by his mother to visit Douglas in Havelock North. The family saw Douglas as one of the last ‘true Victorian gentlemen’. It appears that until 1974 he lived a life of genteel leisure in Havelock North, surrounded by antiques and cultural treasures from around the world that he had inherited from his father and great-grandfather.

During these visits, Douglas told Tim of his family ties with significant Māori chiefs. One of Douglas’s earliest memories was of leaving New Zealand at the age of three or four to return to England with his family for a time. This recollection dates the journey to around 1883. Before embarking the Nairns travelled to Blackhead, near Pōrangahau, to bid farewell to local chiefs, who may have been of Ngāti Hine-te-wai, Ngāti Kere and Ngāti Manuhiri descent.11

What was the Nairns’ connection with Hawke’s Bay? Douglas’s grandfather, John Nairn senior (c. 1792–1883), a gardener turned botanist married to Eliza Liston, a servant, arrived at New Plymouth with his family on the William Bryant in March 1841.12 His son Charles James Nairn (1822–94) had arrived in New Zealand a few months earlier as a member of a survey party. In 1848 John Nairn took up land in southern Hawke’s Bay, and six years later the family acquired Pourerere station, part of the Waipukurau block purchased from local Māori by the government land agent Donald McLean in 1851. In the intervening years Charles Nairn explored widely in the South Island.13

The Nairns imported shorthorn cattle, ran thousands of sheep, and prospered. Charles built a 32-room homestead in 1875, became a member of the Patangata County Council, and died a rich man, bequeathing land valued at £10,000 (equivalent to $1.8 million in 2011) to the Church of England.14

Charles Nairn’s brother John Nairn junior (c. 1831–1916), the first custodian of this remu known to Douglas Nairn, married Edith (nee Gilbertson). Douglas Nairn, their third child, was born in 1879. In the same year Edith’s brother (or cousin), stockbroker Edward Gilbertson, arrived in New Zealand from London. Edward is the great-grandfather of the current generation of Gilbertsons.

We can only speculate about the previous history of this remu. The nineteenth century was a time of much disruption for Māori in Heretaunga (Hawke’s Bay). Many were displaced during the ‘Musket Wars’ by tribes from the north and west. After peace agreements were brokered, many resettled on their customary lands.15 European squatters like the Nairns informally utilised Māori land from the 1840s; later they purchased it from the Crown. There were many disputes over which Māori held customary rights, and whether or not specific land had been sold.16

Was the gifting of this remu an instance of kopaki (the use of mana or personal authority emanating from taonga to secure a dialogue or relationship)?17 There is a tantalising possibility that it was part of an exchange. In 1876, Wellington’s Evening Post reprinted an article from the Edinburgh Courant. The Royal Clan Tartan Warehouse had made to order ‘two sets of Highland costume for a Maori chief … about five feet ten inches in height, strongly built, weigh[ing] twenty-two stone, and measur[ing] fifty-four inches round the chest.’ The dress costume featured a green cloth jacket and scarlet waistcoat. The tartan was Royal Stuart; the device on the sporran and dirk was ‘a semi-savage with war-club over the shoulder’. The client was ‘Mr. John Nairn, of New Zealand’.18 Was this a gift related to a land transaction or a long-standing friendship, or an acknowledgement of chiefly authority analogous to Douglas Nairn’s childhood recollection?

Is this distinctive tartan still in family hands? Does a hidden local connection between Pākehā and Māori wait to be revealed? If so, a remu marereko may yet bring together people across generations.

First published in Fiona McKergow and Kerry Taylor, eds, Te Hao Nui – The Great Catch: Object Stories from Te Manawa, Random House, 2011; updated and republished with the author’s permission.

Footnotes

- This is the correct spelling of his name, not Patarangukai as recorded on the postcard. See Basil Keane, Tūranga i te hapori – status in Māori society – Class, status and rank, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/31108/patara-te-ngungukai, accessed 27 November 2025. ↩︎

- Huia pairs were to be shifted to an island sanctuary at the direction of Augustus Hamilton, director of the Dominion Museum (now Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa). See James Drummond, ‘The Huia Bird’, Evening Post, 18 July 1908, p. 13. ↩︎

- Huia (Heteralocha acutirostris), Te Papa Collections Online, https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/topic/1339, accessed 27 November 2025. ↩︎

- For research that has reconnected kaitiaki with their taonga, see Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Icons Ngā Taonga. Examples include a child’s wrap (p. 37), a rare kahu waero (p. 42) and a peace chalice (p. 44). ↩︎

- While writing this essay in 2011, I was told of a private collection in Wairarapa that has complete skins of both male and female huia. ↩︎

- A set of ‘huia’ feathers held in private hands for a century turned out to be from an Indian myna when examined at Te Papa. For an article on Hokimate Harwood’s research methods, see Harwood, ‘Identification and description of feathers in Te Papa’s Māori cloaks’, pp. 125–47. Note that she has not assessed the remu marereko which is the subject of this essay. ↩︎

- For Valentine’s Wikipedia entry, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Valentine_(photographer) ↩︎

- Maxwell, With the ‘Ophir’ Around the Empire, pp. 157–58. ↩︎

- For instance, Auckland Star, 10 June 1901, p. 3; Wanganui Herald, 14 June 1901, p. 3. ↩︎

- The source of this clipping has not yet been located as the Southland Daily News has not been digitised on Papers Past. The article was, however, printed in the Pahiatua Herald, 2 December 1929, p. 5; Wairarapa Daily Times, 2 December 1929, p. 4, Hawkes Bay Herald, 3 December 1919, p. 7; and Taranaki Daily News, 21 December 1929, p. 1 (supplement). ↩︎

- Personal communication from Peter Sciascia, July 2011. These hapū are an autonomous group from the Pōrangahau area. See Ballara and Scott, Crown Purchases of Maori Land in Early Provincial Hawke’s Bay. ↩︎

- ‘Mr and Mrs John Nairn and family’, series of photograhic prints, 1847–1867, Puke Ariki, A66.197, https://collection.pukeariki.com/objects/28909/mr-and-mrs-john-nairn-and-family, accessed 27 November 2025; Jane Tolerton, Household services – Gardeners, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/household-services/page-4, accessed 27 November 2025. ↩︎

- The Cyclopedia of New Zealand, Volume 6, Taranaki, Hawke’s Bay and Wellington Provincial Districts, Cyclopedia Company, Christchurch, 1908, pp. 407, 410–11; T.E., ‘Nairn, Charles James (1822–94)’; Hawke’s Bay Herald, 17 May 1862, p. 4. ↩︎

- Cyclopedia, p. 407; Jane Tolerton, Household services – Gardeners, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/household-services/page-4, accessed 27 November 2025. ↩︎

- Ballara and Scott, p. 2. ↩︎

- For one example, see Hawke’s Bay Herald, 17 May 1862, p. 4. ↩︎

- Smith, ‘Mana Taonga’, p. 24. ↩︎

- Evening Post, 8 January 1876, p. 2. ↩︎

Bibliography

Ballara, Angela and Gary Scott, Crown Purchases of Maori Land in Early Provincial Hawke’s Bay: Report on Behalf of the Claimants to the Waitangi Tribunal, Waitangi Tribunal, 1994, see https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_172204949/Wai%20201,%20I001.pdf

Harwood, Hokimate, ‘Identification and description of feathers in Te Papa’s Māori cloaks’, Tuhinga, no. 22, 2011, pp. 125–47, see https://www.tepapa.govt.nz/assets/76067/1692673985-tuhinga-22-2011-pt4-p125-147-harwood.pdf

Maxwell, William, With the ‘Ophir’ Around the Empire: An Account of the Tour of the Prince and Princess of Wales, 1901, Cassell, London, 1902, http://www.archive.org/stream/withophirroundem00maxwrich/

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Icons Ngā Taonga: From the Collections of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2004.

Smith, Huhana, ‘Mana Taonga and the Micro World of Intricate Research and Findings around Taonga Māori at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa’, Sites: A Journal of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies, vol. 6, no. 2, 2009, pp. 7–31.

T.E., ‘Nairn, Charles James (1822–94)’, in G.H. Scholefield (ed.), A Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, vol. 2, Department of Internal Affairs, Wellington, 1940, p. 114.

Leave a comment