Pauline Knuckey

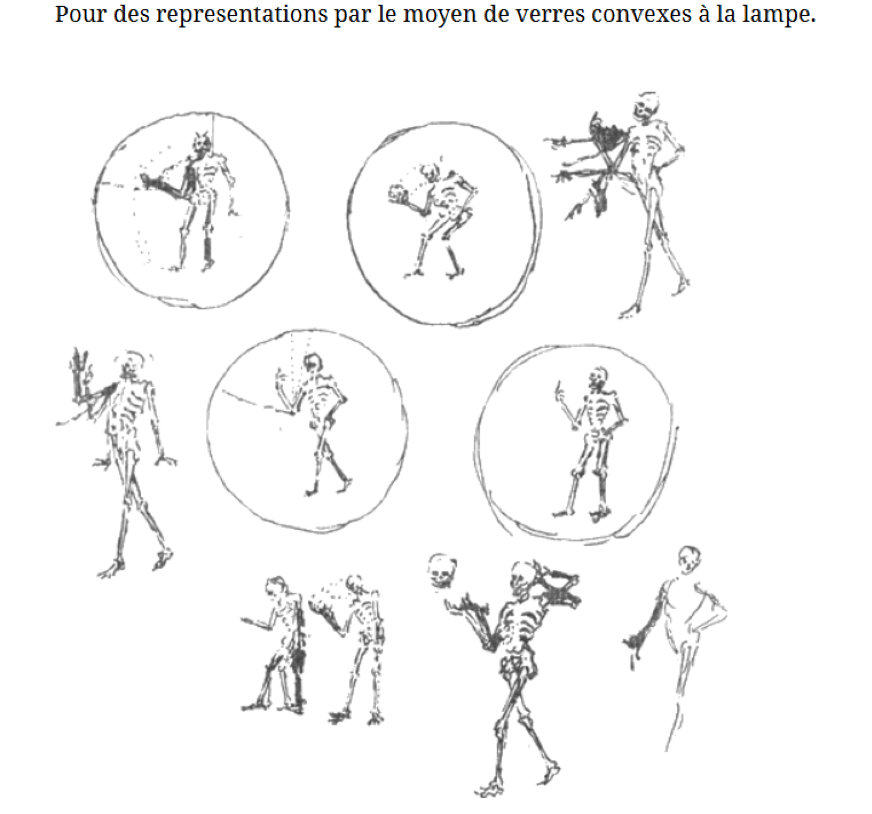

Magic lanterns have been around since the 1600s, long before photographs, slide projectors and moving pictures were invented. Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens is generally believed to have invented the magic lantern. His 1659 drawings of a skeleton called Death taking its head off, under the heading ‘For representations by means of convex glasses with the lamp’ (translated from French) are the oldest known documents on magic lanterns.1

The lantern operated with a light source, usually a candle in its very early years, placed in front of a concave mirror which reflected the light through a small illustrated glass slide – a lantern slide – and onward to a lens at the front of the apparatus. The lens pushed the image on to the projection screen, which was often just a blank wall. The slide got its name from the action of sliding the glass plate into place. Use of the word in this context has continued right through until today when we talk of adding content to slides in PowerPoint software.2

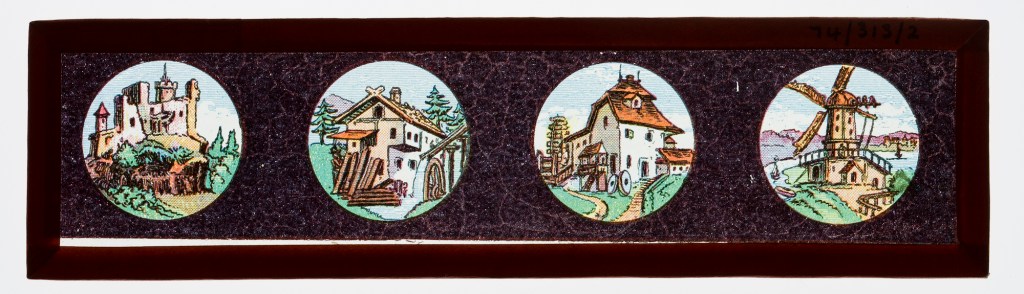

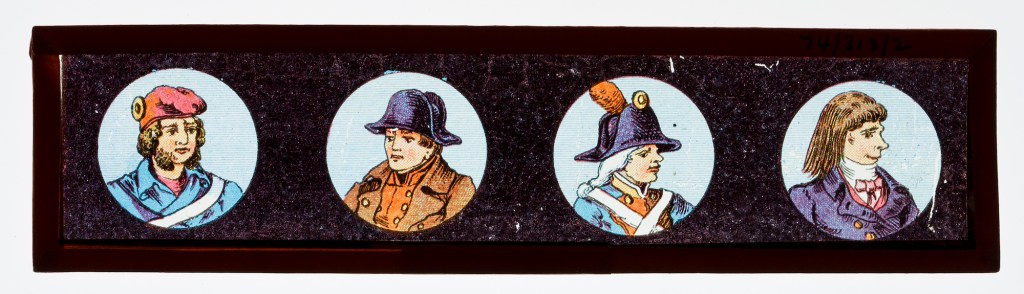

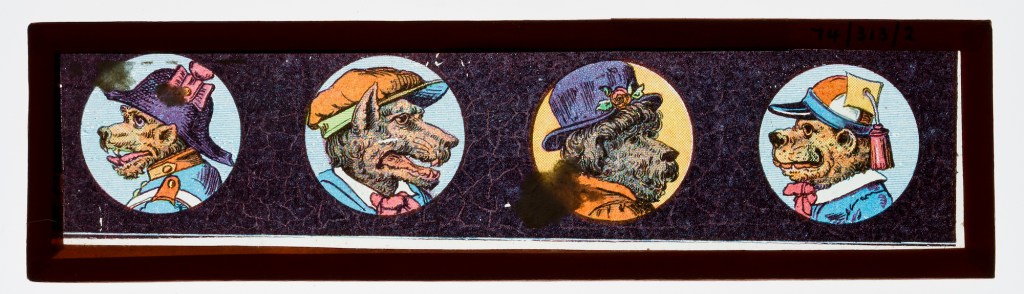

Originally, images on the slides were painted with black paint but colour was soon introduced. Most handmade slides were mounted in wooden frames with an opening for the slide. While candles were the earliest form of illumination, along with oil lamps, lighting improved with the Argand lamp in the 1790s, limelight in the 1820s, and the arc lamp in the 1860s. These eliminated the need for gases and chemicals, making the lamps considerably safer and easier to use.

There are three magic lanterns held at Te Manawa Museum. The one featured below was donated by Frederick Norman Callesen, a prolific donor to the museum, and comes with a set of twelve slides. It shows a slide mounted in the bracket, waiting to be moved into place between the light source and the lens. For the purposes of the photo the slide has been placed upright, but when in operation the slide is placed upside down as the mechanism reverses the image onto the screen.

The lantern itself is in excellent condition and has obviously been well looked after. It has an upright rectangular black steel body with a chimney vent at the top, a brass lens at the front and a door on one side, for easy access to place the illumination tool. The feet are gilt metal and the door is a raised geometric design. It was made in Germany, possibly by the Ernst Plank Company, although it does differ from examples known to have been made by this company in subtle ways.3

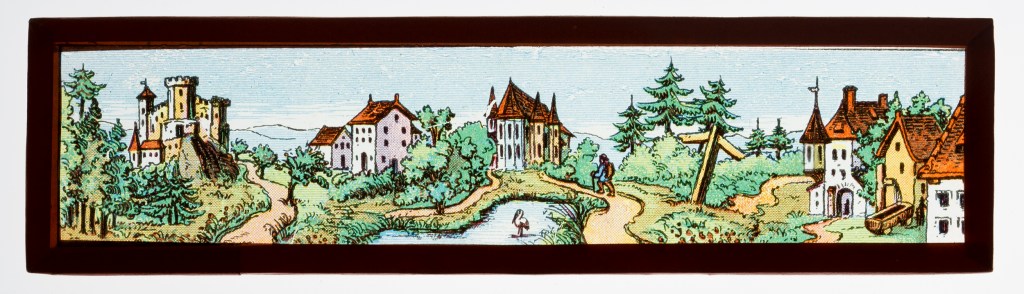

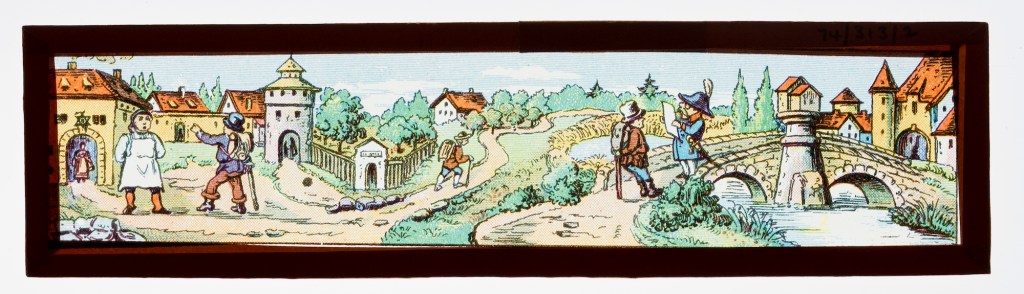

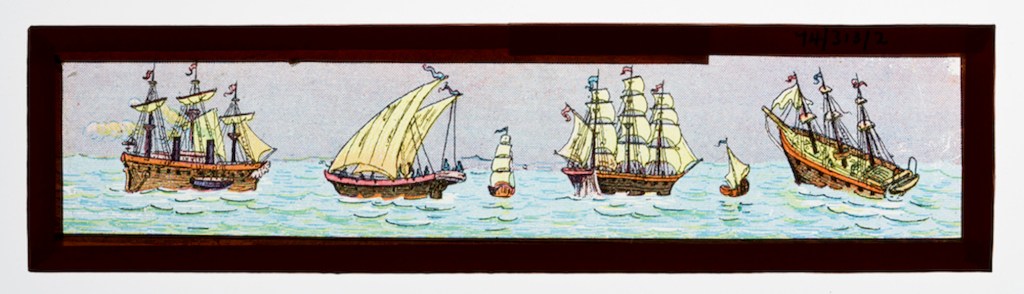

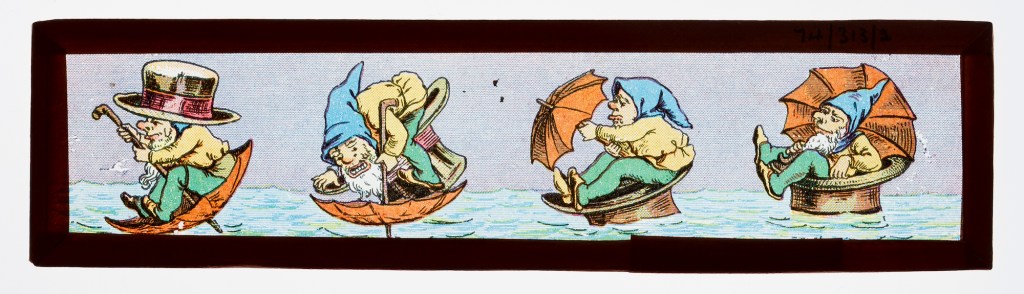

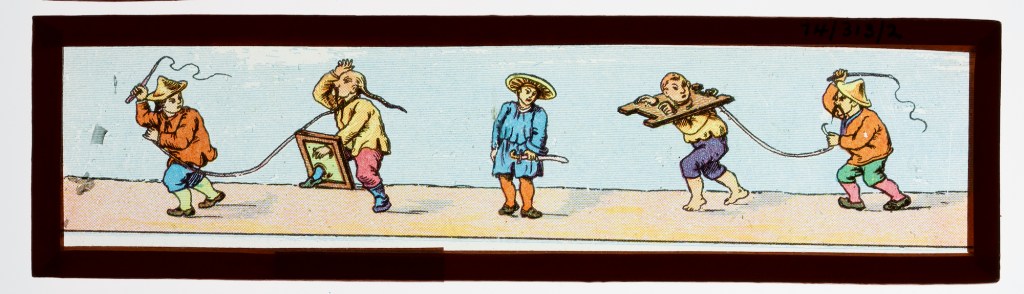

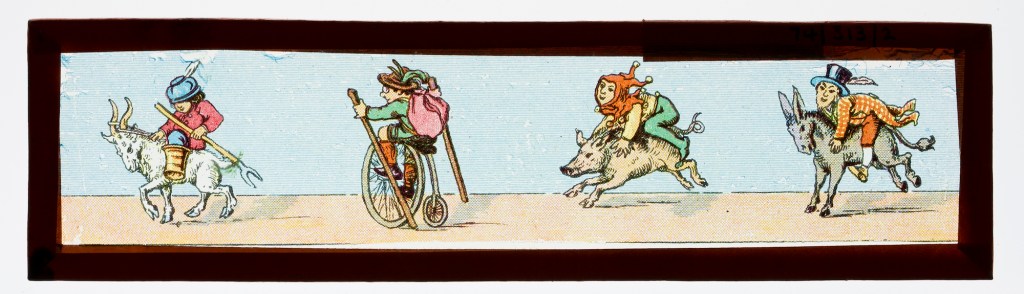

The sequence of children’s slides shown above were produced by the Ernst Plank Company. Started in 1866, and named after its founder, the company mainly built toy steam engines and magic lanterns. These can still be found on auction sites such as Trade Me and eBay, the steam engines in particular being especially collectible given their relative scarcity.

The magic lantern and slides were owned by Fred’s father, Volle Callesen. The Callesen family were of Danish origin. Volle and Emma (née Demler) were married in 1882. They were living at Awahou South in Pohangina Valley by 1884. Fred was born there on 1 September 1899, the tenth child and seventh son; Volle and Emma had 13 children in total between 1883 and 1904.

Fred initially attended the newly established Awahou South School, built in 1902. His mother died in 1904 and the younger Callesen children were brought up by their sister Theresa. When his father purchased a farm at Raumai on the other side of the valley in 1911, Fred attended Raumai School.

In 1914 Volle moved to Karere near Longburn and in 1918 to a farm on Pukehou Road, Bulls. Fred did not marry and remained living with his unmarried sisters, Emma and Theresa, on the family farm after their father’s death in 1931. Fred was a farm worker all his life. He died in 1989.4

Along with the magic lantern and twelve slides, Fred donated a phonograph and wax cylinders to the Manawatu Museum in the mid-1970s. These items were used by his father to entertain local children – no doubt both his own and other school children given that he was on the Awahou South School committee – and neighbours. While magic lanterns were originally seen as entertainment, primarily for children, as they developed, so did the desire to portray them as something other than a toy or gimmick based on ‘magic’. This shift was helped along with developments such as animated images and the use of photography in the preparation of slides. They began being used for scientific and educational purposes and were popular with schools and churches where they could successfully combine a mix of informative slides along with those for pure entertainment.5

New Zealand followed this international trend and this is borne out by the many newspaper reports of their usage. The earliest mention of a magic lantern was made in the New Zealand Gazette and Wellington Spectator on Saturday 14 August 1841, although in this case it was used to argue a political point rather than to advertise a show.6 Throughout the 1840s magic lanterns were advertised for sale, but it was not until 15 March 1851 that the first public use of a magic lantern was recorded in a newspaper, the Lyttelton Times.7 From then, reports of public screenings became commonplace. The New Zealand Spectator and Cook’s Strait Guardian reported on a large gathering of 250 children from Wellington’s Church of England schools attending an Easter Monday function where they were given tea and cake and enjoyed the attractions of a magic lantern.8 A few years later this same function attracted 500 children who gathered at Thorndon School for an afternoon of games and tea, followed by an evening with a magic lantern, where its ‘never failing stories of instruction and merriment … was highly appreciated’.9

There was no shortage of magic lantern screenings for local audiences either. The Foresters’ Hall in Palmerston North was the venue for a fundraising bazaar for a new Wesleyan Church in December 1882. Along with music and a museum, the evening entertainment included a magic lantern screening. The event was deemed a great success with nearly 200 pounds raised.10 The Foresters’ Hall was again the venue for a pictorial presentation of Dr Livingstone’s African explorations. The evening was made up of two parts with the second being ‘experiments with the magic lantern’ which created ‘no small amusement amongst the juveniles, who mustered in strong numbers upon the occasion’.11 A 13-year-old writer to the Manawatu Herald provided a lengthy report of a magic lantern screening given by a Mr Patten who promised a prize to the best writer. After describing the scenes of Polar region explorations and monuments along the River Nile, the author claimed:

[T]he children were most pleased with the animals, especially the elephant with the boy who had been teasing him; then there were pictures of Punch and Judy which were very amusing; there was another one with a boy on a little donkey’s back, and every minute it would rear up and send the boy almost over his head.12

The writer concluded that they all enjoyed his show very much, with the evening passing away ‘very pleasantly, so wishing him many thanks for his pleasant show’.13 While children were the predominant audience of magic lantern entertainment, it was noted that ‘older heads were not above enjoying the infantine amusement’.14

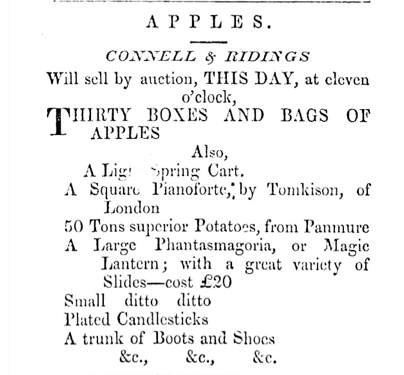

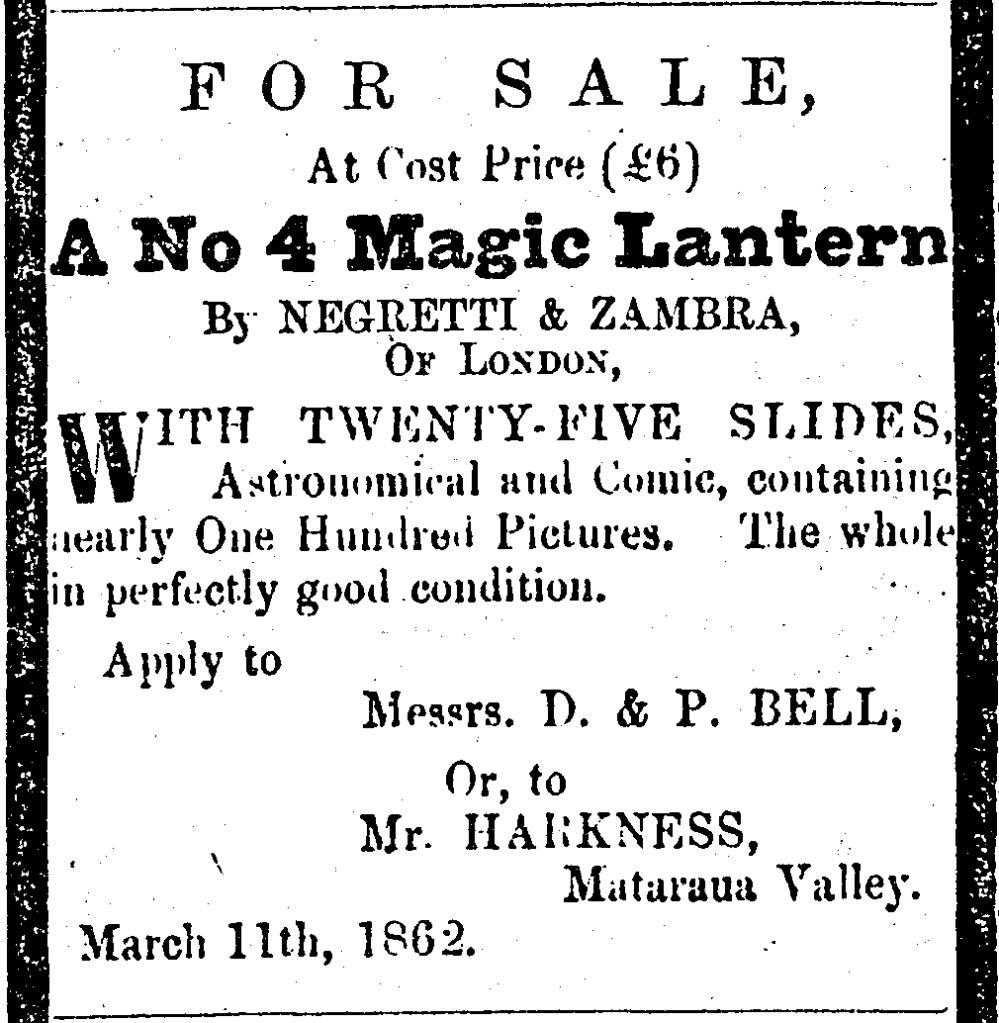

Newspaper reports clearly show that, from the mid-nineteenth century, magic lanterns were frequently used for public entertainment around the country. Given the number of advertisements for magic lanterns it is safe to assume these also ended up in private homes, as the Callesen one did. Purchasers would have needed to shop around given that prices varied considerably. An advertisement in the New Zealander had a magic lantern on offer for a hefty 20 pounds, while the Wanganui Chronicle had one for sale for six pounds four years later.15

Magic lanterns continued to be frequently used throughout the country, in both urban and rural settings throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Their popularity faded however, with the introduction of the moving picture, a phenomenon that completely captivated audiences. The magic lantern did continue to be used, albeit in a reduced capacity throughout the first half of the twentieth century, although the introduction of the slide projector in the 1950s effectively brought about its demise. The social and technological impacts of the magic lantern were considerable and it is no surprise it was called ‘the mother of the cinema industry’.16

Footnotes

- Vollgraff, Christiaan Huygens, Oeuvres Complètes, p. 197. ↩︎

- Jolly and deCourcy, The Magic Lantern at Work, p. 3. ↩︎

- Unlike the Ernst Plank Company magic lantern at Te Papa, it is does not have an ‘E.P.’ trademark. See Slide projector, ‘Magic Lantern’, GH003284/1-19, Te Papa Collections Online, URL: https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/64715 (accessed 7 September 2025). ↩︎

- Burr, Mosquitoes & Sawdust, pp. 111–12. ↩︎

- Jolly and deCourcy, The Magic Lantern at Work, p. 1. ↩︎

- New Zealand Gazette and Wellington Spectator, 14 August 1841, p. 2. ↩︎

- Lyttelton Times, 15 March 1851, p. 5. ↩︎

- New Zealand Spectator and Cook’s Strait Guardian, 19 April, 1854, p. 3. ↩︎

- Lyttelton Times, 6 May 1857, p. 5. ↩︎

- Feilding Star, 2 December 1882, p. 3. ↩︎

- Manawatu Times, 17 May 1879, p. 2. ↩︎

- Manawatu Herald, 18 October 1889, p. 2. ↩︎

- Manawatu Herald, 18 October 1889, p. 2. ↩︎

- Otago Witness, 2 January 1858, p. 5. ↩︎

- Wanganui Chronicle, 20 March 1862, p. 2; New Zealander, 13 February 1858, p. 2. ↩︎

- Evening Star, 19 August 1940, p. 6. ↩︎

Bibliography

Burr, Val A., Mosquitoes & Sawdust: A History of Scandinavians in Early Palmerston North and Surrounding Districts (Skandia II), The Scandinavian Club, Palmerston North, 1995.

Jolly, Martyn and Elisa deCourcy (eds), The Magic Lantern at Work: Witnessing, Persuading, Experiencing and Connecting, Routledge, New York, 2020.

Vollgraff, J.A. (ed.), Christiaan Huygens, Oeuvres complètes, Tome 22, Supplément à la correspondance, Various, Biographie, Catalogue de vente, The Hague, 1950. URL: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/huyg003oeuv22_01/huyg003oeuv22_01_0093.php (accessed 8 September 2025).

Leave a reply to Simon Johnson Cancel reply